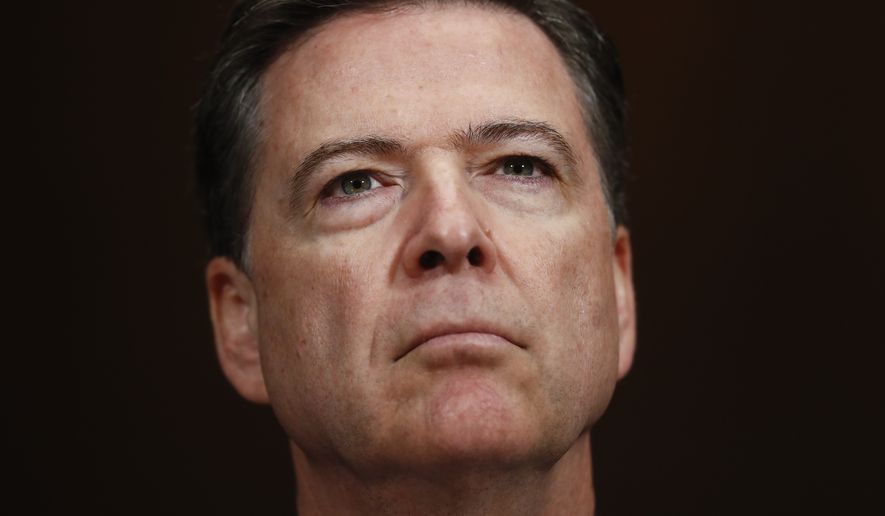

It was James Comey’s fierce independence that won him praise and a 93-1 Senate confirmation vote to become the seventh director of the FBI.

But that same independent streak also appears to have been his undoing.

Justice Department leaders based their recommendation to fire Mr. Comey on the director’s decision to speak out of turn on the closure of the Hillary Clinton email investigation — noting his actions usurped the authority of prior Attorney General Loretta E. Lynch.

When President Obama nominated Mr. Comey to take over leadership of the of the bureau in 2013, one story was shared frequently as evidence of his ability to stand up for integrity regardless of the political pressures he faced. While serving as deputy attorney general under President George W. Bush, Mr. Comey won praise for his handling of a 2004 incident in which White House officials rushed to a hospital room to try to get an ailing Attorney General John Ashcroft to reauthorize a warrantless wiretapping program. Mr. Comey had himself declined to signed the order and was present at the bedside of Mr. Ashcroft.

A Republican nominated for the FBI director’s post by a Democratic president, Mr. Comey was a curiosity in Washington. But over the course of the last year, Mr. Comey’s apolitical approach earned him scorn from both sides of the aisle.

At the outset of 2016, Mr. Comey’s biggest controversy was the bureau’s battle with tech company Apple over locked phones.

The FBI’s determination to access encrypted information stored on a phone used by one of the San Bernardino shooters triggered a battle between privacy rights activists and law enforcement. The FBI was later able to get the phone unlocked through a private company rather than a court order, but Mr. Comey had argued that Apple’s default use of encryption technology was making the country less safe by limiting law enforcement agencies’ abilities to investigate terrorism and other crimes.

Just a few months later, a chance meeting on an airplane between former President Bill Clinton and then-Attorney General Lynch laid the groundwork for what became Mr. Comey’s downfall.

On July 5, Mr. Comey called a news conference to announce that at the conclusion of the FBI’s yearlong investigation into Mrs. Clinton’s use of a private email server during her time as secretary of state. He called Mrs. Clinton’s handling of top-secret information “extremely careless,” going so far as to say that enemy hackers may have breached her email server, but he concluded no “reasonable prosecutor would bring such a case.”

Just last week, Mr. Comey testified to Congress the he felt compelled to describe his own reasoning for taking the unusual step and speaking publicly about a case in which no charges would be brought because he believed that the June 2016 airport tarmac meeting between Ms. Lynch and Mrs. Clinton’s husband, former President Clinton, had undermined the Justice Department’s credibility to independently investigate the case.

“A number of things had gone on, which I can’t talk about yet, that made me worry that the department leadership could not credibly complete the investigation and decline prosecution without grievous damage to the American people’s confidence in the justice system,” Mr. Comey told senators last week.

Republicans were flummoxed by the July announcement that no charges were being brought.

At the time, Mr. Comey had yet to alienate supporters he might have had among Democrats. That changed significantly just two weeks before the November presidential election, when Mr. Comey wrote to Congress to inform lawmakers that the FBI was had reopened its Clinton email investigation.

The case was reopened, he told lawmakers, after agents recovered new emails as part of a separate case: the sexting charges against former Rep. Anthony D. Weiner, the estranged husband of top Clinton aide Huma Abedin.

A review of the emails was completed just days before the election, and Mr. Comey announced two days before voters went to the polls that Mr. Weiner’s computer turned up no new evidence of wrongdoing on Mrs. Clinton’s behalf. For Democrats, the damage was done.

Mrs. Clinton lost the election to Mr. Trump, a loss she blamed, in part, on Mr. Comey.

Mr. Comey’s four years as FBI director coincided with a rise in terror attacks carried out by homegrown violent extremists in the United States, as well as activism by the Black Lives Matter movement against police brutality.

In his first major television interview as FBI director, given to “60 Minutes” nearly a year after he was confirmed to the post, Mr. Comey mostly talked about terrorism and cybercrime — problems that to this day he has stressed as important to tackle.

But relationships between law enforcement agencies and the communities they serve became a hot topic later after a series of protests over police killings began to turn violent.

Mr. Comey was among the high profile law enforcement leaders who believed that officers nationwide are policing less aggressively because of some high-profile racially-charged incidents and the explosion of videotaped encounters. The FBI director said in 2015 that he thought the so-called “Ferguson effect,” coined after the Missouri town where riots broke out after a white police officer fatally shot a black 18-year-old, could be making officers less proactive — and emboldening criminals.

“I don’t know whether that explains it entirely, but I do have a strong sense that some part of the explanation is a chill wind that has blown through American law enforcement over the last year,” Mr. Comey said in 2015, acknowledging that no data yet exists that could prove or disprove the idea.

Before being sworn-in, Mr. Comey served as an assistant U.S. attorney for the Southern District of New York and the Eastern District of Virginia between stints at McGuireWoods law firm. After he became the U.S. attorney for the Southern District of New York in 2002, he oversaw the conspiracy and securities fraud case lodged against Martha Stewart.

In 2003, he became the deputy attorney general for the Justice Department, but left in 2005 to become general counsel of the Lockheed Martin Corporation, then the nation’s largest defense contractor.

• Andrea Noble can be reached at anoble@washingtontimes.com.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.