OPINION:

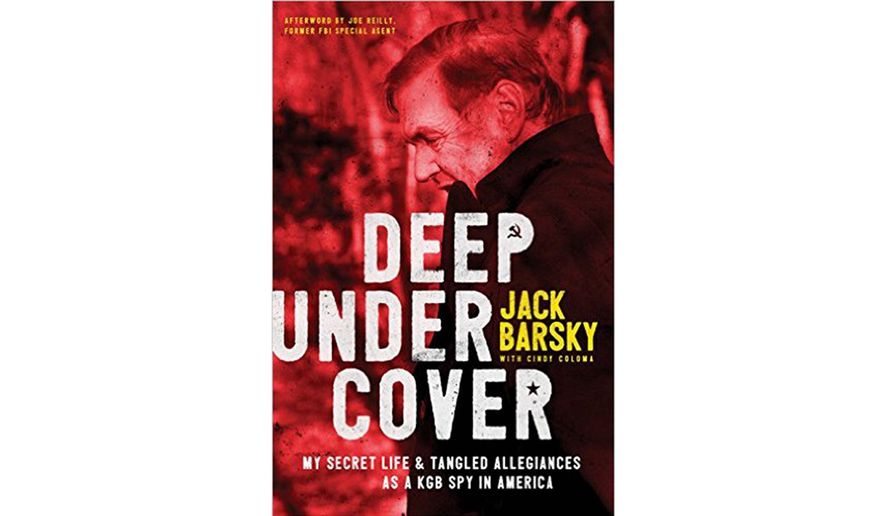

DEEP UNDERCOVER: MY SECRET LIFE AND TANGLED ALLEGIANCES AS A KGB SPY IN AMERICA

By Jack Barsky (with Cindy Coloma)

Tyndale Momentum, $24.99, 352 pages

Everyone loves a good spy story. But it can be hard to tell if the story is fact or fiction; this is especially the case with spy memoirs. Jack Barsky’s page-turning memoir, “Deep Undercover,” has a ring of authenticity to it. Most of the book is written using recreated dialogue, but is it true?

Part of Mr. Barsky’s story was told by “60 Minutes” and it reads like the best of spy fiction: While he was a prize-winning chemistry student in East Germany, the KGB recruited Mr. Barsky to become an illegal agent abroad. An illegal is one of Russia’s most secret agents. The spy is sent to the target country under an assumed identity and is told to build a life acquiring all the necessary documentation.

In this case, Albrecht Dittrich was transformed into Jack Barsky through a birth certificate of a dead United States citizen. After Mr. Dittrich arrived he was told to obtain a library card, a driver’s license, a Social Security card and a passport in order to become “legal.” The book provides an inside look into the making of a spy, his experiences, his inner thoughts, his assumed identities and KGB spycraft. Above all, it shows how life as a deep cover spy affected his personal and family life.

Reader’s familiar with the illegals program as depicted in the TV show “The Americans” (based on the real story of 10 captured Russian illegals in 2010) may be aware that illegals integrated themselves into American society; they may not be aware of the pre-deployment training. In Mr. Barsky’s case, it took eight years from the time he was recruited at the university in 1970 until he arrived in the United States in 1978 to become operational, including four-and-a-half years of intensive training.

Spy training took place in Jena, East and West Berlin, Canada and Moscow where he learned basic spycraft like how to send and listen to messages with a short-wave radio, prepare secret messages, develop photographic skills, and service a dead-drop. Most importantly, he was tutored about Western ideology, culture, language, TV and human contacts. In fact, the KGB mantra was “contacts, contacts, contacts” reflecting their emphasis on human intelligence. Mr. Dittrich was also provided with an English language tutor in East Germany and during his two-year stay in Moscow before his deployment.

In fact, one of the most striking aspects of the story is how long it took to train him and the KGB’s long-term investment. This style of espionage seems unique to the KGB and the East Bloc. U.S. intelligence, for instance, tends to operate with shorter recruitment periods and probably never had an illegal planted in the Soviet Union.

Spy life, however, took a toll on his personal life. There were long periods of loneliness and isolation. The KGB also frowned on relationships with women, even though he had a “weakness for the fairer sex.” He married an East German woman who tolerated his long absences abroad; they only saw each other every two years. She even gave birth to Mr. Barsky’s baby boy and raised him alone. Meanwhile, he married a woman in New York City who bore him a daughter who he adored and bonded with.

Mr. Barsky does not know why the KGB recruited him, but his science background fit their drive to expand scientific-technical intelligence during the 1970s. He majored in computer science at Baruch College, became the valedictorian and worked in IT, an intelligence acquisition focus. Mr. Barsky writes very little about what he actually passed on to his KGB handlers save to mention an acquired software program. Most of the “spy story” reads like an immigrant makes good story from lowly bike messenger to top executive.

His case is remarkably similar to that of Werner Stiller, who was also an East German, though he was recruited by the Stasi’s Sector for Science and Technology in 1972 while he was a physics student. He eventually defected to West Germany, landed in America, was debriefed by the CIA, received a new identity, earned an MBA, learned English, got married five times, and left his two children in East Germany. Some of his memoirs turned out to be false to confuse the enemy. Even if spies aren’t born with duplicitous personalities, the double life leads to personal and professional betrayals and a kind of schizophrenia.

Despite the omissions in what he acquired for the Soviets, Mr. Barsky’s memoir shines light on a signature Russian program. Mr. Barsky so successfully imbedded himself in America that he became one of us and chose to stay with his family rather than return to the Soviet Union when he was recalled. Mr. Barsky’s combination of academic intelligence and street smarts likely helped him avoid jail time when he cooperated with the FBI after they discovered him.

Kristie Macrakis, the author or editor of five books, teaches at Georgia Tech.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.