NEWSMAKER INTERVIEW:

Pakistan’s military has swept terrorist groups from the nation’s once-lawless tribal areas, but the gains could be put at risk if the security situation across the border in Afghanistan is not brought under control, Islamabad’s diplomat in Washington said, stressing that his nation is waiting for the Trump administration to clarify its strategy for the Afghanistan conflict.

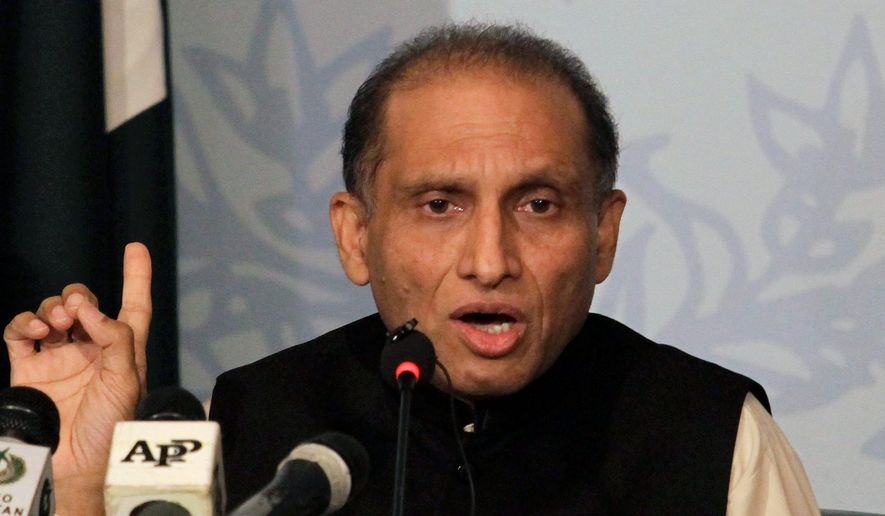

Ambassador Aizaz Ahmad Chaudhry said his country’s reputation as a source of instability and a haven for jihadis is badly out of date. He argued that Pakistan’s economy is on a sharp upswing and that relations with Washington are stronger today than at any other time since the covert American commando raid that killed al Qaeda founder Osama bin Laden in his Pakistani hideout six years ago.

“There are some perceptions which are not fully up to speed with the new reality of Pakistan, a reality that has changed only very recently,” Mr. Chaudhry told editors and reporters of The Washington Times. “We have reversed the tide of terrorism, which had come down heavy on us.”

Having just arrived in Washington in March, Mr. Chaudhry took care to neither openly praise nor criticize the Trump administration’s foreign policy. As “an honored guest” of the U.S., he is eager to deal with the man whom American voters chose as their president, he said.

At the same time, he said Pakistan was a strong supporter of the global Paris climate accord. President Trump withdrew the U.S. from the agreement last week.

“There are issues on which Pakistan has its own positions regardless of what the U.S. position is,” said Mr. Chaudhry, noting that Pakistan is at risk of flooding as Himalayan glaciers melt. “We supported the Paris talks. We committed to it.”

On another front, the ambassador went to lengths to credit China just as much as Washington for helping spur remarkable economic progress. Pakistan’s economy is on pace to grow at an annual 6 percent rate next year, and predictions say it could emerge among the world’s top 20 by 2030 — a dramatic rise from its current rank in the 40s.

The stock market in the predominantly Muslim nation of roughly 200 million people is booming, Mr. Chaudhry said.

The biggest foreign investment — some $60 billion in recent years — is from Beijing, which sees Pakistan as a key conduit for development in China’s mainly Muslim western region, he said. China has poured money into energy projects aimed at easing Pakistan’s electricity shortages.

But the boldest investment is the development of a major deep-sea port in Gwadar, designed to open Pakistan’s southern coastline to trade routes in the Arabian Sea and Indian Ocean, a critical link in Chinese President Xi Jinping’s “One Belt One Road” growth strategy for wider Asia and beyond.

Moment of stability

The Chinese investments have coincided with a rare moment of political stability in Pakistan, after the nation’s first-ever successful transition from one democratically elected government to another in 2013.

The transition of power, which brought back former Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif, followed decades of military coups, assassinations and other upheaval, including massive anti-corruption demonstrations that marred the nation’s 66-year history.

Over the past decade, the instability was spiked by a bloody campaign of suicide bombings and other attacks by al Qaeda and other jihadi groups on civilian and government targets. But an aggressive counterterrorism campaign launched by the Sharif government in the northwest Federally Administered Tribal Areas has sharply reduced such violence, Mr. Chaudhry said.

“The number of terrorist incidents, which used to be very high, up to 150 terrorist incidents per month on the average right up to 2014, is today down to single digits,” the ambassador said. “That has sent a very positive wave all across the country.”

Mr. Chaudhry said hopes are high that foreign investment will grow amid prospects for another smooth transition after elections next year.

Pakistan’s improving economic picture means that “the Koreans, the Turks, the European and corporate America are also coming in,” with energy plants being built along the nation’s southern coastline. “The next phase for us is to build a series of industrial zones,” he said. “We are expecting and attracting investments, and many of the European countries are particularly keen.

“So with our labor, the Chinese want to bring in capital, and if the technology can come in from the West, I think it would be an ideal combination for everybody,” the ambassador said.

The U.S. has sent roughly $2 billion a year in aid to Pakistan in the past two decades. The majority of the money was aimed at supporting the Pakistani military. But Mr. Chaudhry said corporate America is beginning to sense opportunities.

“I think they are able to see what, perhaps, you and I are not able to see,” he said.

General Electric Co. recently won a project bid to generate 3,600 megawatts of electricity in Pakistan, and Exxon Mobil Corp. has put together a consortium to spend roughly $800 million to build a liquefied natural gas terminal and “gasifying plant” near the new southern seaport.

“[It’s] why Procter and Gamble is there, why PepsiCo is there, why many companies are going there,” Mr. Chaudhry said. “They’re not going because they want to put their money at risk; they are going there because they can see that there is some money to be made.”

The trouble next door

But the ambassador stressed that all of Pakistan’s regional and economic ambitions could be derailed if the situation continues to deteriorate in neighboring Afghanistan, where the number of attacks by extremists, including the Islamic State, is on the rise.

On Wednesday, a massive truck bomb rocked the heavily fortified diplomatic quarter of Kabul, killing 90 people and underscoring the challenge facing Afghan leaders and American and Pakistani officials seeking to stabilize the war-torn country, Mr. Chaudhry said.

“How does the United States want to deal with their huge investment in Afghanistan, both militarily and economically? We are waiting for it,” the ambassador said. He was referring to a highly anticipated shift in U.S. strategy that the Trump administration has said will be announced in the coming weeks.

“We think that the United States also wants to stabilize Afghanistan,” he said. “Why? Because you have invested hugely in blood and in treasure for the last 15 to 16 years [there].”

One plan reportedly being circulated through the White House and the Pentagon calls for up to 5,000 more U.S. troops, with a matching commitment from NATO, which could bring to roughly 15,000 the total number of foreign troops in Afghanistan.

Mr. Chaudhry did not take an explicit position on a proposed troop increase but said any use of military force should be tied to a push for a political solution to the conflict in Afghanistan. Such a push, he said, should include the pursuit of a peace process with the Taliban.

The jihadi insurgent group, which once harbored al Qaeda and bin Laden in Afghanistan, has extended its grip on territory since U.S. forces ended their combat mission in Afghanistan in 2014.

A “modest surge” of American forces now, said Mr. Chaudhry, might pressure the Taliban to embrace peace talks with the U.S.-backed government in Kabul that have stalled for years. “Once [the Taliban] are weakened, they will come to the table,” the ambassador predicted, but he said the Afghan government should lead the peace process.

Pakistan’s proximity to the situation is delicate. Despite its internal success against jihadi groups over the past three years, Islamabad faces accusations that its intelligence services are clandestinely backing certain extremist groups inside Afghanistan.

Pakistan also harbors millions of Afghan refugees. The ambassador said Islamabad hopes they will be allowed to return home soon.

Afghan intelligence officials claimed that one that of those groups, the Haqqani network, was responsible for the attack in Kabul last week.

Mr. Chaudhry vehemently rejected the accusation during his interview with The Times. “Pakistan has absolutely nothing to do with the Haqqanis and the Taliban,” he said. “They do not represent the views of my people and we have squeezed the space on them” in Pakistan.

• Carlo Muñoz can be reached at cmunoz@washingtontimes.com.

• Guy Taylor can be reached at gtaylor@washingtontimes.com.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.