ANALYSIS/OPINION:

It’s never as simple as us versus them. And even though America’s victory in her war of independence from Great Britain would eventually see her become the most powerful nation in the world’s history, the causes, factors and fallouts from that initial armed conflict are as complex as they are numerous.

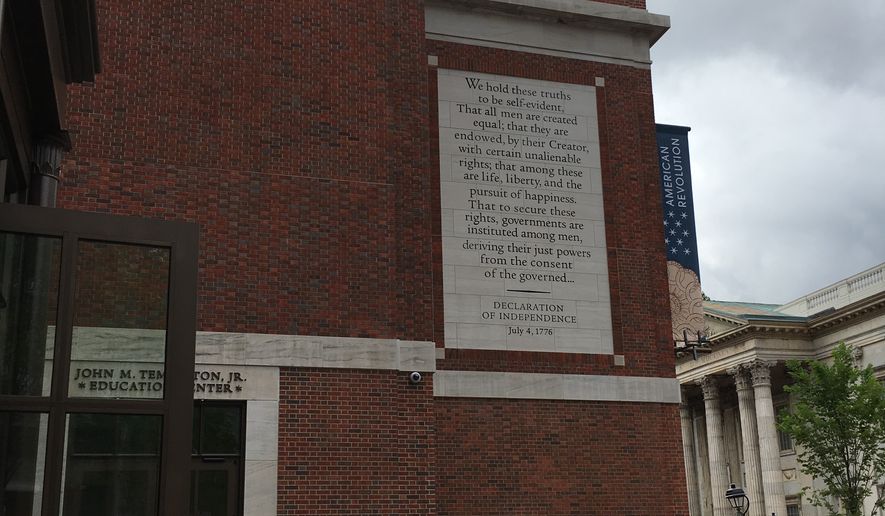

Thankfully, the new Museum of the American Revolution in Philadelphia has done a beyond-admirable job of explicating how not just decades but in fact centuries of events were as crucial — if not more so — to America’s fiery birth as the “Shot Heard Round the World” at the Battle of Lexington in Massachusetts April 19, 1775, marking the “official” outbreak of armed hostilities between the Colonists and King George III’s forces.

Upon entering the exhibit halls, you are encouraged to sit and watch the first film in the galleries. In less than 20 minutes, the professional-quality movie offers a primer on the conflict, from the Boston Massacre of 1770, on through Lexington and Concord, the signing of the Declaration of Independence not far from here on July 4, 1776, then on through seven more long, arduous years of war that saw its high point with Gen. Washington’s victory at Yorktown against Cornwallis Oct. 19, 1781.

And, finally, the singing of the Treaty of Paris Sept. 3, 1783, thereby recognizing the United States of America as a new nation entirely independent from the Crown.

The museum exhibits are helpfully subdivided into four distinct periods: 1760-1775 (“Road to Independence”), 1776-1778 (“The Darkest Hour”), 1778-1783 (“A Revolutionary War”) and 1783 to present (“A New Nation”). Each gallery warehouses helpful panels to explicate even the minutiae of the life, politics, religions and philosophies of early America, and showcase artifacts including uniforms, weaponry, maps, documents and various other precious relics of the late-18th century.

Too often forgotten, and here brought into the limelight, the stories detailing the contributions of both African-American and American Indian soldiers, citizens and activists from the time period are also presented. That blacks and Native Americans suffered terribly in the saga of early America — and, it must be said, since — is not in doubt, and the Museum of the American Revolution does a paramount effort at making sure that those lesser-known voices are heard. Videos and audio recordings of traditional American Indian ceremonies are heard, as are vintage tales and music that came from the slave culture.

Homage is also paid to the many, many blacks and American Indians who fought in the Revolution — and in every conflict since. (Some tribes cast their lot with the British, partly to keep French expansion into their territory at bay, but partly out of fear of the Americans. Furthermore, as they would do again in the War of 1812, British forces even offered freedom to enslaved African-Americans to fight against the Yankees.)

Furthermore, the term “American” in the 18th century was itself a misnomer. In addition to the “native-born” whites who fought against King George, immigrants from across Europe also took up arms in their adopted land. Exhibits also detail the areas of Germany from where the British hired mercenaries, known as Hessians, to bolster their forces in the New World — many of whom were embarrassingly, and drunkenly, surprised on the morning after Christmas in 1776 by Washington at the Battle of Trenton in New Jersey. Be sure to look for room-size reproductions of Emanuel Gottlieb Leutze’s famous 1851 painting, “Washington Crossing the Delaware.”

(New Jersey happens to be my home state, and every Christmas, weather permitting, there is staged a recreation of Washington and his troops rowing across the Delaware from the Pennsylvania side to land at the appropriately named Washington Crossing State Park.)

As important to the men who served on the fields of battle were the contributions of America’s early women to the cause of freedom. Tribute is paid in various exhibits not only to such known figures as Martha Washington, Abigail Adams and Mary Ludwig Hays, aka “Molly Pitcher,” but also to slave Elizabeth “Mumbet” Freeman, the first person to successfully petition the state of Massachusetts for her freedom in 1781.

I also learn that the initial constitution drawn up for New Jersey, my home state, briefly granted women’s suffrage — though only to certain property owners — from 1776-1796. Despite such a forward-looking measure, it would be another 124 years until the Constitution finally granted all voting-age women the franchise.

And while the image of a united America fighting against British occupation is indeed convenient, it is far from truthful. Loyalists to London, those who hustled back across the Atlantic before the war and those who stayed, earned the scorn of their neighbors, and there were many disputes as to how the war with England should be carried out — if at all. Prejudices among the Colonists were rampant, not just against minorities and Indians, but against other regions of the Colonies. There were several times that even Washington himself feared loss was imminent.

That a cohesive strategy ever resulted, or that victory was its conclusion, remains awe-inspiring, especially considering the mostly nonprofessional forces mustered to take on the titanic might of His Majesty’s professional armies.

As war is necessarily a two-sided affair, rightful prominence is given to the English perspectives too. Letters and diaries of English generals, politicians, soldiers and peasants tell of the golden age of empire, when the Union Jack represented the most powerful realm in the world up to that time. Career soldiers were sent to quell rebellion in the Colonies not because they were malicious, but because it was their job to do so as ordered by their sovereign.

The 13 Colonies were the possessions of King George, and armed anti-insurgency was necessary to keep them.

As it so happens, my girlfriend Victoria is from the U.K. As we walk the museum together, I am somewhat surprised to learn from her that the American Revolution bears almost no mention in English history classes. Mulling this tidbit over, it begins to make a little more sense from both a historical and cultural perspective: It was the first war the world’s greatest military had truly ever lost (#nationalpride) and, perhaps even more importantly, American history entails barely 400 years, whereas the history of Britannia goes back millennia.

Ergo, this little dustup with a rebellious satellite of the empire, in the grand scheme of British history, likely merits but a footnote.

That said, Victoria is thoroughly pleased with the museum today, and as her knowledge of the conflict between her home country with the nation where she now lives was so little taught in her youth, she’s grateful for the better understanding the museum gives her — and from both sides.

We all learned about Betsy Ross’ flag in elementary school, but be sure to take a gander at the various other standards that were designed and briefly used as America’s national symbol.

And make sure to sit through the video describing Gen. Washington’s field tent, at the conclusion of which, the screen rises to reveal the 200-plus-year-old fabric. It’s a precious artifact, and thus no touching or photographs are permitted, but simply to behold the humble quarters of the general and America’s first president is a humbling sight indeed.

Furthermore, an exhibit explains that Washington, upon being elected the first president, eschewed the proposed title of “His Excellency” in favor of “Mr. President,” the honorific still in use. Also cognizant of breaking from European-style rule for life, Washington stepped down in 1797 after two terms in office — long before term limits were mandatory.

And in step with a swords-to-plowshares tradition harking back all the way to the Roman Cincinnatus, Washington, the career soldier and reluctant politician, returned to his estate at Mt. Vernon in Virginia, where he would pass into history but two years later — mere miles from the site of the future capital city that bears his name.

It’s a lot to take in, and don’t feel badly if you can’t see it all in one visit. But do make sure to visit the interactive dress-up room to don some vintage 18th century clothing.

I did.

The Museum of the American Revolution is located at 101 S 3rd St, Philadelphia, Philadelphia, 19106 (steps from both Independence Hall and the Liberty Bell and the nearby Penn’s View Hotel) and is open daily from 9:30 a.m. to 7 p.m. Visit AmRevmuseum.org for more information and tickets.

• Eric Althoff can be reached at twt@washingtontimes.com.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.