OPINION:

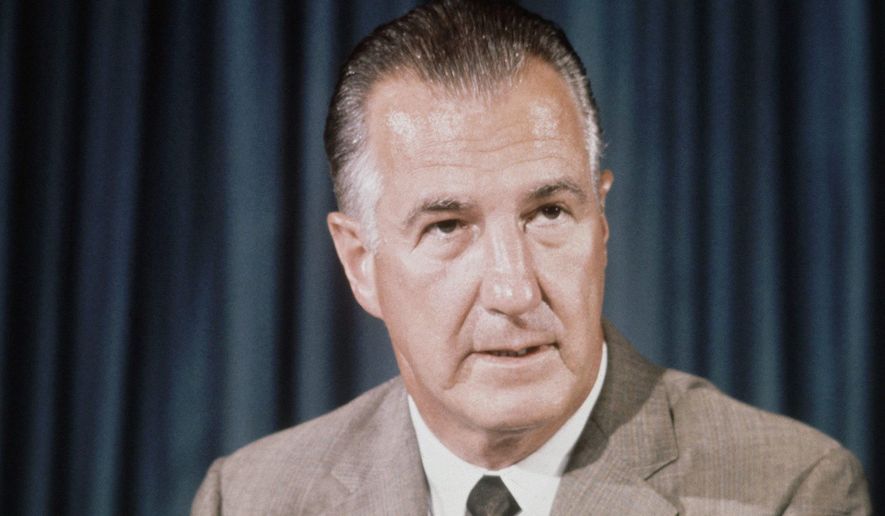

On Nov. 13, 1969, Spiro T. Agnew walked to the podium in Des Moines, Iowa, to deliver perhaps the most famous speech ever by a U.S. vice president. It was, of course, the famous “Des Moines Speech” in which Mr. Agnew for the first time took on broadcast media commentators in a way that must make President Trump green with envy.

The speech, crafted by Mr. Agnew and President Richard Nixon’s conservative speech writer, Pat Buchanan, attacked what has since come to be known as “media bias,” thrilled Republicans and conservatives who had long before concluded that the media was unfair and infuriated the liberal and journalistic establishments of the day.

The vice president was warned by many, including former President Lyndon Johnson, that it was foolhardy to take on the media because it was a battle that couldn’t be won, the same advice showered on President Trump today.

Mr. Agnew then, like Mr. Trump today, focused his criticism on television’s talking heads and news readers, describing them as “a tiny and closed fraternity of privileged men, elected by no one and enjoying a monopoly sanctioned and licensed by government.” The impact of the speech was immediate. The White House and the networks on which he focused received tens of thousands of telegrams in that pre-Twitter era with most agreeing with the vice president. NBC reported that more than 85 percent of those contacting the network supported Mr. Agnew’s views and the vice president quickly became the overnight hero of millions of Americans whose views coincided with his.

It was, however, in some ways at least, a gentler time. Today, commentators call out our current president as a liar, psychotic or Russian agent, and print columnists don’t hesitate to call the man a “pig.” But in the ’60s, before The New York Times argued that reporters have some sort of divine obligation to take down politicians with whom they disagree, bias was more subtly expressed. Mr. Agnew charged, “A raised eyebrow, an inflection of the voice, a caustic remark dropped in the middle of a broadcast can raise doubts in a million minds about the veracity of a public official or the wisdom of a governmental policy.” The problem then was the homogeneity produced by the bubble in which commentators worked. As Mr. Agnew observed in trying to explain the day’s bias, “these commentators and producers live and work in the geographical and intellectual confines of Washington, D.C. or New York City. Both communities bask in their own provincialism, their own parochialism. We can deduce that these men thus read the same newspapers, and draw their political and social views from the same sources. Worse, they talk constantly to one another, thereby providing artificial reinforcement to their shared viewpoints.” Little has changed since other than that the atmosphere within the bubble in which these folks live has become even more toxic than it was then.

Mr. Agnew charged that “a narrow and distorted picture of America often emerges from the televised news.” Anyone who ventures far from New York or Washington would have to agree with those words today. The issues that consume the commentariat have little resonance in Peoria, Des Moines or Redding. Television’s talking heads are ready to impeach President Trump over issues that most Americans care little about or believe are the rantings of conspiracy theorists with little connection to reality.

Little has changed in the interim except that back then, the media elite claimed its critics were lying because journalists and commentators were unbiased seekers of truth; today they wear their prejudices like badges of honor as they attack those with whom they disagree.

In the aftermath of the Des Moines speech, polls showed that vast majorities of Americans agreed with the vice president, but wished things would quiet down. He never backed down, but knew that the public eventually backs away from combatants who do little other than attack their opponents. As a result, he shelved plans to deliver a follow-on speech targeting the print media, arguing that while raising the issue was important, it was dangerous to talk about nothing else. That is something that neither the Democrats and journalists who do little other than attack Mr. Trump these days — nor Mr. Trump himself — have yet learned.

• David A. Keene is editor at large at The Washington Times.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.