Filmmaker Barak Goodman is a student of history. He in fact majored in the subject in college but, by his own admission, didn’t care for the field at the time “because of the way it was taught.”

“But when you become a professional storyteller, which is what a documentary filmmaker is, and you can look at history as a sort of narrative, then it’s a whole other thing,” Mr. Goodman told The Washington Times.

Accordingly, Mr. Goodman’s new film, “Oklahoma City,” returns to the site of the horrific April 19, 1995, bombing of the Alfred P. Murray Federal Building, resulting in the deaths of 168 men, women and children and the maiming of dozens more.

Mr. Goodman’s film, which premieres Tuesday on PBS’ “American Experience,” takes a three-part narrative structure. It begins with the armed confrontation between federal agents and white supremacist elements at Ruby Ridge in Idaho before segueing into the standoff in Waco, Texas, between the Branch Davidians and federal agents.

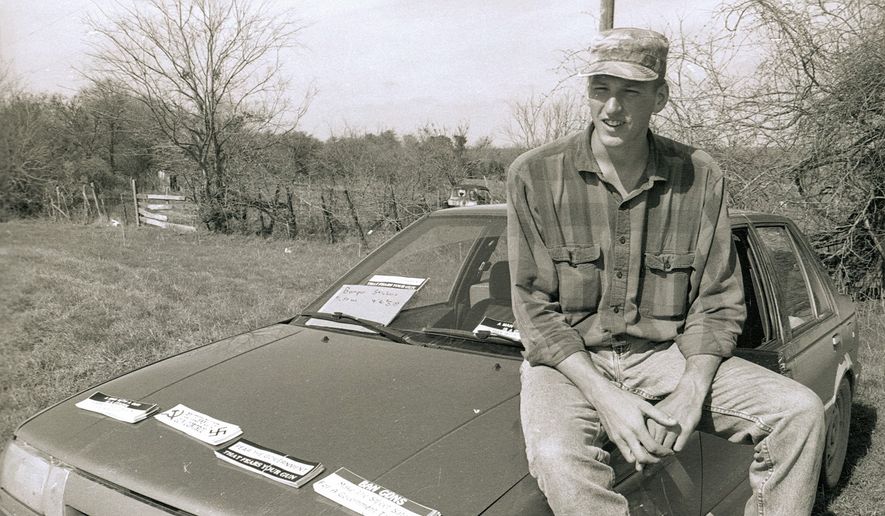

A young man, an Army veteran, is seen at Waco in archive news footage decrying the federal government.

His name was Timothy McVeigh. And after the disastrous end to the Waco siege, the stage was set for his plan to blow up a truck bomb in Oklahoma City alongside co-conspirator Terry Nichols.

Mr. Goodman, who counts fellow documentarians Ken Burns and Errol Morris among his heroes, said that his aim with “Oklahoma City” was not to show the story of the bombing’s planning, execution and aftermath in black-and-white terms, but rather to show all sides of not only how it happened, but why it happened.

“It’s more interesting for a film to embrace complexity than it is to have an argument,” he said, adding that documentary filmmakers should “be open” to finding the story rather than imposing their preconceived narrative on the film.

Mr. Goodman, who was Oscar-nominate for his 2000 documentary “Scottsboro: An American Tragedy,” spent many months researching his subject, including visiting the site of the bombing and its attendant memorial. “Oklahoma City” traces in much detail how McVeigh and Nichols carefully chose their target in Oklahoma City, then made plans to deliver what they hoped would be a crushing blow to the U.S. government and stoke racial animus at the same time.

McVeigh and Nichols were ultimately caught and convicted of the bombing. McVeigh was executed in 2001, and Nichols remains in a supermax facility in Colorado for life without the possibility of parole.

In addition to showing the investigation and trail that led to their convictions, Mr. Goodman spends as much time interviewing federal workers at the Murrah Building, first responders and law enforcement officials who, not even knowing if more bombs awaited, continued to pull survivors from the wreckage.

Even now, nearly a quarter-century after the incident, some subjects still would not discuss the tragedy on camera.

“With first responders it’s so palpable and fresh to them,” Mr. Goodman said, adding that one interviewee even canceled on the day he was to be filmed. “But generally we got pretty good cooperation,” the director said.

Nearly 22 years after the incident, Mr. Goodman said part of his aim was to shine a spotlight on not only the horror, but also the heroic efforts of first responders, law enforcement and ordinary people who came to the add of both their neighbors and complete strangers.

Furthermore, his motivation was to “bring to light the fact that there is a movement, going back to the founding of the republic, that holds the federal government in such contempt that violence is permissible,” he said, noting that such elements continue to operate throughout the United States even today.

“Oklahoma City was a moment where it just sort of burst out into the open. And then it kind of recedes again,” he said, adding that actors such as Dylann Roof appear every few years to remind that the violent anti-government movement lives on. “There are a lot of people out there who have these views of the world, and they’re willing to act violently.

“This movement has never gone completely away; it kind of waxes and wanes throughout American history,” Mr. Goodman said. “I want to remind people that these domestic terror events are part of the fabric of life.”

Furthermore, Mr. Goodman says he hopes that viewers take away the fact that the federal government, such as that represented in Oklahoma City, is not a “monolithic thing” but rather comprises people simply going about their days to do their jobs.

“McVeigh completely lost sight of that,” Mr. Goodman said. “We hope to enlighten people that … human beings are the federal government.”

Mr. Goodman advises other documentary filmmakers to seek out stories that are not clear-cut but rather entail an element of “moral grayness.”

“Go for the ambiguity,” he said. “Don’t show things as black and white because they never are.”

“Oklahoma City” airs Tuesday on PBS.

• Eric Althoff can be reached at twt@washingtontimes.com.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.