OPINION:

The Affordable Care Act is in a “death spiral,” warns Aetna CEO Mark Bertolini. Premiums have doubled since the end of 2013, and yet insurers are rapidly exiting the individual market, leaving consumers in many parts of the nation at risk of having no coverage.

Washington politicians have 10 weeks to produce a remedy. That’s the deadline for insurers to announce their 2018 health plans and premiums.

Sadly, congressional Republicans are bickering like firefighters arguing over the best route to a burning house. House Speaker Paul Ryan proposes subsidies from Uncle Sam for people to buy private health plans. Conservative lawmakers such as Sen. Rand Paul reject that idea as Obamacare-lite, warning the nation can’t afford another entitlement.

The way out of this political logjam is to lower premiums in the individual market so substantially that buyers don’t need a subsidy.

Mr. Ryan’s plan will do the opposite, pushing premiums even higher. Just look at how federal college loans and aid have pushed college tuition to the stratosphere. Expect insurance subsidies to do the same.

Americans want lower premiums and deductibles, every poll shows. The remedy is funding care for the 5 percent sickest people separately, through high-risk pools, instead of relying on premiums paid in by healthy people. Premiums will drop by hefty double digits the first year. The healthy will be able to buy coverage on their own — just like they did before Obamacare.

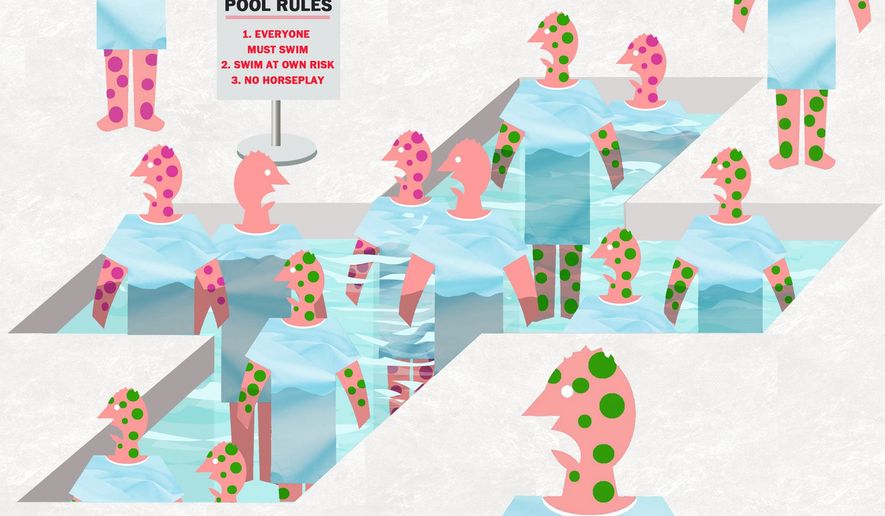

Obamacare’s fatal defect is well known. It forced two groups — the healthy and the chronically ill — into the same insurance pool at the same price. A person with pre-existing conditions on average consumes 10 times as much health care as a generally healthy person.

Healthy people would pay premiums but never meet their deductibles. Instead, the premiums would be used to pay for the sick.

The healthy could see it was a ruse and refused to sign up, causing insurers to lose $2 billion a year and abandon the market.

As Mr. Bertolini explained, at Aetna “the top 1 percent to 5 percent of our members, depending on the marketplace, are driving 50 percent of our overall cost structure.”

No surprise here. The sickest 5 percent of Americans account for 50 percent of health care spending.

It’s basic math. The fair way to deal with skewed health needs is for Congress to subsidize coverage for the very sick with taxpayer dollars, instead of making healthy people overpay. Congress can do this quickly, funding high-risk pools (or reinsurance funds) in every state as part of its current budget legislation. Paying for people who develop chronic and costly illnesses separately will remove the largest costs from the individual insurance market, lower premiums, and save the market from collapse.

There are, at most, 500,000 people in the individual market who would need high-risk coverage — not the millions Democrats claim. In the years before Obamacare, only 250,000 people were turned down each year by major insurers because of pre-existing conditions, according to government reports. Enrollment in state and federal high-risk pools serving the uninsurable peaked at 340,000. Even taking into account that some may have needed the help but not applied, the number is still under half a million.

Covering each of them will cost at least $32,000 a year, based on recent risk-pool experience. All in all, that’s $16 billion or more a year. It’s a small price compared with the $56 billion the nation currently shells out on Obamacare subsidies.

Federally funded high-risk pools will target money directly to the sick, instead of paying healthy people to buy overpriced insurance. (Mr. Ryan claims to use high-risk pools but his plan provides a mere $2.5 billion a year, not enough to make them work.)

Voters sent Republicans to Congress to repeal Obamacare and make insurance affordable again. High-risk pools will halt the insurance “death spiral” and substantially lower premiums. Lawmakers have 10 weeks to get it done.

• Betsy McCaughey is a senior fellow at the London Center for Policy Research.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.