OPINION:

Which side are you on, the presumption of innocence or a boss’ right to fire for sexual harassment, without furnishing proof?

This question is not as easy as you may think.

When employers of late went public with each sexual-harassment head-chopping, it may have looked to some as if all that’s required to cost a man his reputation and career is an accusation.

It appeared to some skeptics that all the employer needed to hear from an accuser was that the employee, by word or deed, had brought pain and embarrassment to her. Or to him, in the case of the once-revered ex-Metropolitan Opera conductor James Levine who stands accused of homosexual abuse, and the actor and self-proclaimed homosexual Kevin Spacey who is also accused.

Remember Minnesota Public Radio saying it fired Garrison Keillor, 75, based on an accusation of “inappropriate behavior” by an unnamed person who worked with him on “A Prairie Home Companion.” That was it. An accusation. No proof. No conviction in a court of law.

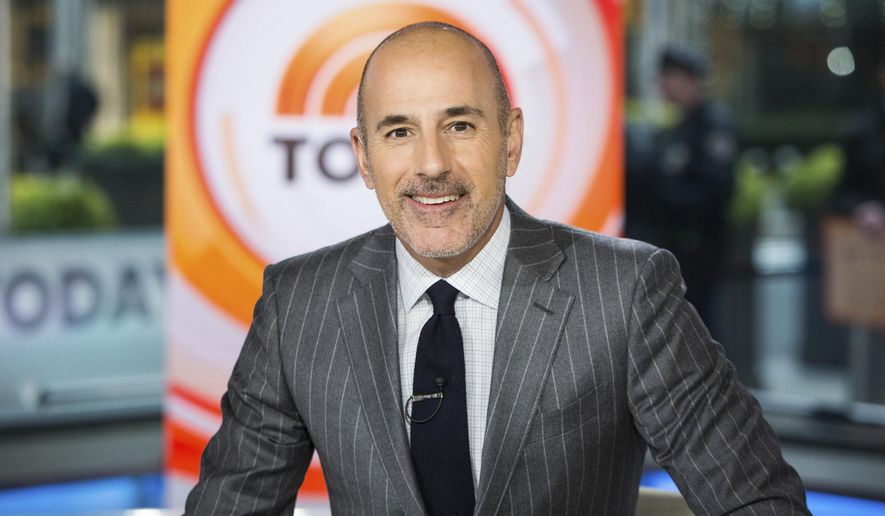

Same with the firing of “Today” show’s Matt Lauer, the biggest fish in audience reach to get fried so far.

Turns out he was a sexual predator who used his position in the NBC hierarchy to force sex on women subordinates, according to women who went public about him after NBC bounced him. The women’s stories don’t rise to the “Exhibit A” level of courtroom evidence, but he doesn’t deny them.

We know that now but didn’t know it when his employer, without offering evidence of misdeeds, announced the firing in this tweet:

“Matt Lauer has been terminated from NBC News. On Monday night, we received a detailed complaint from a colleague about inappropriate sexual behavior in the workplace by Matt Lauer. As a result, we’ve decided to terminate his employment.”

People for whom the presumption-of-innocence rule is preeminent thought it a bit worrisome that, on the basis of one complaint about him in his 20-some years with NBC, he got booted. What happened to the rule of law, the nation’s foundation? What’s changed?

The change is a newfound willingness of the sexually aggrieved to speak up about old transgressions that they once had feared to make public. Precisely why that fear suddenly has transformed to a compelling desire to speak out will be probed and debated.

What hasn’t changed is the right of private employers to pink-slip anyone for any reason or no reason. It’s been that way since Benjamin Franklin and his friends gave us a republic and challenged us to keep it.

Now, this right to fire does have exceptions, some of them statutory. You can’t toss someone for race, or gender, or for exercising the right to testify truthfully in a court of law — even if they’re testifying about what a cheat and scoundrel you are.

This private-sector right to fire without cause is as it should be. You can’t run your businesses right as the owner or CEO if you can’t drop from your payroll workers you think are nincompoops, or underperformers, or simply redundant.

For one thing, I can imagine a competitor across the street — or in Beijing — getting his operatives on your payroll. They’d turn your business belly up before any proof of guilt could squeeze through the appeals-laden legal system.

For another thing, imagine being forced to substitute a court of law for your own judgment about trimming your workforce. And by the way, the First Amendment bars only governments, not private businesses — like, say, NFL teams — from firing employees for the views they express in words or in the knees they take.

So a newspaper or TV network owner or boss can kick you out the door for expressing a view he doesn’t like. Such firings are not free-speech issues.

So there’s little in the harassment firings that threatens the rule of law.

From Harvey Weinstein and Charlie Rose to Mark Halperin, Kevin Spacey and Louis C.K. — it developed that the employers who fired the alleged offenders did know more than they disclosed initially. They were following the advice of counsel and were confident they had the goods on the accused.

Meanwhile, the accused stated sputtering defenses that sounded shady at best.

Neither denying nor confirming anything, Mr. Keillor word-knotted his response into an indecipherable something that wobbled between an apology and an apologia. He was “fired over a story that I think is more interesting and more complicated than the version MPR heard.” By way of non-explanation, he added, “I cannot in conscience bring danger to a great organization I’ve worked hard for since 1969. I am sorry for all the poets whose work I won’t be reading on the radio and sorry for the people who will lose work on account of this.”

Say what?

In a similarly airy arrangement of words, Mr. Lauer said he was sorry for any pain that might have been felt by those who thought he had caused them pain.

“Some of what is being said about me is untrue or mischaracterized, but there is enough truth in these stories to make me feel embarrassed and ashamed,” the former $25-million-a-year man said.

Mr. Keillor, Mr. Lauer and CBS-PBS intellectual-sounding interviewer Mr. Rose aren’t claiming their respective employers dumped them on the basis of fake news.

So, yes, it’s understandable to have felt uneasy initially about those announced firings unaccompanied by evidence.

The truth is this: Not only is it a good thing that private and not-for-profit organizations may fire at will — unless of course you’re the one that got busted. But it’s also comforting that any employer with normal survival instincts doesn’t jettison employees for harassment unless he and his legal team have the evidence.

Fear of bad publicity, public outrage and defamation suits tend to focus a boss’ mind on the merits of honesty.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.