OPINION:

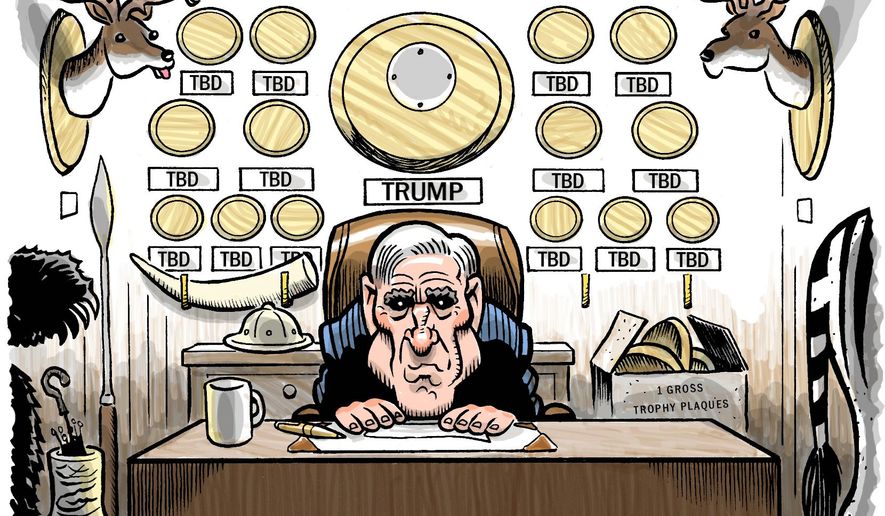

Robert Mueller, like virtually every special prosecutor or independent counsel preceding him, has embarked on what amounts to a witch hunt that will allow him to brag when it’s over that he indicted a bunch of those he went after — even if he never manages to unearth any evidence that the Trump campaign “colluded” with the Russians.

Those who don’t “cooperate” with Mr. Mueller’s team now know they can expect the treatment visited upon former Trump campaign manager Paul Manafort: early-morning raids, demands for millions of dollars as bail and multiple indictments. Those who agree to say what Mr. Mueller and his band of brothers and sisters seek, on the other hand, will be treated like retired General and former National Security Adviser Michael Flynn. Neither Mr. Manafort nor Mr. Flynn has been charged with “colluding” with Moscow to help Mr. Trump’s 2016 campaign, but each has seen what happens when prosecutors decided to “get” them.

In Mr. Manafort’s case, the charges stem from business activities predating his involvement with the Trump campaign. They may or may not be meritorious, but the activities for which he is being taken down have nothing to do with the reason Mr. Mueller was appointed in the first place. The fact is that the prosecutor wanted Mr. Manafort to help get others, and when he wouldn’t or perhaps couldn’t because what they wanted him to say simply wasn’t true, they decided to make him an example to others reluctant to cooperate.

Mr. Flynn was indicted not for anything he did during or after the campaign, but for “lying” to a federal agent. The conversations he had with Russian Ambassador Sergey Kislyak were perfectly legal, but he denied having them when initially approached by Mr. Mueller’s team. Dissembling or lying to a federal agent is a standalone crime and doesn’t need to have been uttered under oath. If an FBI agent can lead one into uttering an untruth, he’s got what he needs for an indictment.

Mr. Flynn apparently lied to cover up not a crime, but any contact with the Russians, presumably to deny Mr. Trump’s attackers from using a perfectly legal conversation with the Russian ambassador to further their collusion narrative. It was stupid and made him a vulnerable target who may now be prepared to tailor his testimony to conform with Mr. Mueller’s theories. If Mr. Mueller’s team is simply looking for scalps rather than evidence that anyone actually “colluded” with the Russians, they will get them, but measuring their success by counting indictments of this sort proves little about whether anyone actually “colluded” with Vladimir Putin’s Russia.

Americans like to hold our justice system up as the most just on earth and it may well be, but only because we are competing with some that don’t even deserve to be called justice systems. Prosecutors are all-powerful when they decide to go after someone. In Flynn’s case, prosecutors apparently threatened to indict not only the general, but his son unless he would cooperate.

Mr. Mueller’s gang is expert at this sort of thing. Consider the past performance of Mueller deputy Andrew Weissmann, who has proven time and again that he will go to any length to “get” his target. When he doesn’t like someone like, say, Donald Trump, he goes after his target like a mad dog, making up his own rules as he goes along. Mr. Weissmann was involved in the Enron prosecution and decided he wanted to “turn” 30-year-old Ben Gilsan against his superiors. He did so by indicting the hapless Gilson on 26 felony counts and forced him under threat of a lifetime behind bars to plead guilty to one. Mr. Gilsan agreed and was carted off to begin serving his sentence, but said he couldn’t testify to what Mr. Weissmann was really after. Mr. Weissmann wanted more and told associates, according to former federal prosecutor Sidney Powell, that he had a “hunch” he could turn Gilsan. To do this, Mr. Weissmann’s team had Gilsan thrown into solitary confinement for nearly two weeks, broke him and got him to say what Weissmann’s team wanted.

In another case, Mr. Weissmann had a young executive, through whose hands some of the paperwork in the case had passed, indicted and arrested, opposed bail for the young man and had him incarcerated in a particularly gruesome federal maximum-security transfer center hundreds of miles from his home and family. The poor fellow was there for eight months until a federal judge ordered his release. He was later exonerated completely, but according to Ms. Powell, he still won’t talk about what he endured while penned up with some of the most dangerous and violent felons in the country.

These sorts of activities remind one of the Soviet prosecutors during the Stalin era who forced prisoners to confess to crimes they hadn’t committed. Perhaps Mr. Weissmann and his boss picked up pointers reading Arthur Koestler’s “Darkness at Noon.”

• David A. Keene is an editor at large at The Washington Times.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.