Fusion GPS, the opposition research firm whose Democrat-financed Russia dossier fueled an FBI investigation into Donald Trump, pitched other stories about the Republican presidential candidate to Washington reporters, including an attempt to tie him to a convicted pedophile who was once buddies with former President Bill Clinton.

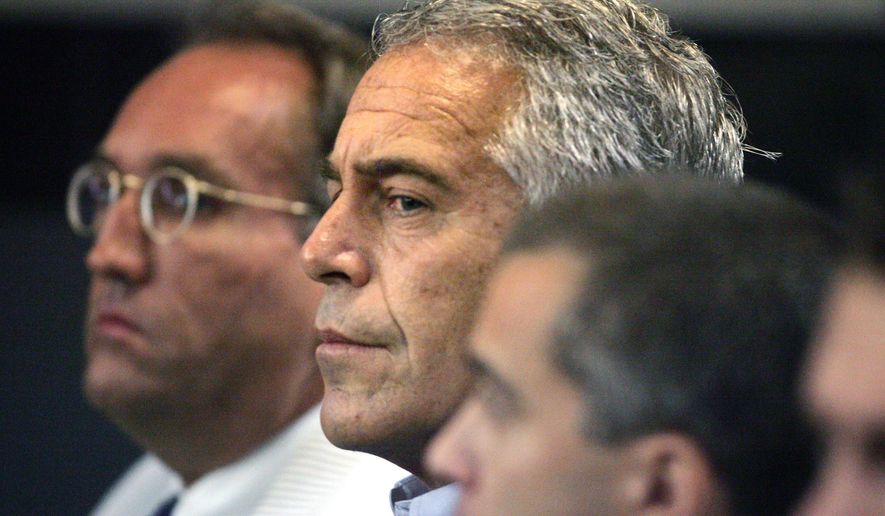

Journalist sources told The Washington Times that Fusion founder Glenn Simpson pushed the idea of a close relationship between Mr. Trump and Jeffrey Epstein, who pleaded guilty in 2008 to soliciting sex from an underage girl.

The Trump-Epstein link appears purely social, far short of Mr. Clinton’s 20-plus plane rides on Epstein’s “Lolita Express” private jet around the globe in the early 2000s.

Ken Silverstein, the reporter who ultimately wrote an Epstein-Trump report, confirmed to The Times that Fusion had sourced the story. Mr. Silverstein, founder and editor of WashingtonBabylon.com who wrote the story for Vice.com, defended Mr. Simpson as a solid source of information that must first be confirmed.

For years, Fusion GPS has been an influential hidden hand in Washington, with entree into the city’s most powerful news bureaus.

Behind the scenes, the private intelligence firm run by former Wall Street Journal reporters was particularly active last year working to defeat Mr. Trump. Fusion leader Mr. Simpson, who railed against sleazy opposition research as a reporter, harbored a strong desire to bring down the builder of hotels with, well, opposition research.

SEE ALSO: Democrats pursue Donald Trump prostitute story

Fusion representatives met with New York Times reporters during the Democratic National Convention in July 2016.

Ironically, it appears The Times was the first to out Fusion on Jan. 11 as the source of the scandalous dossier that BuzzFeed posted the previous day. BuzzFeed did the posting without identifying Fusion or dossier writer Christopher Steele, a former British spy.

“The New York Times, I know they work with Fusion,” said Mr. Silverstein, an investigative reporter who skewers the left and right. “Fusion works with a lot of big media organizations. That would give them influence in Washington.”

“I have worked with them,” he said. “I have gotten tips from them and stories from them. And every time I do, I go out and re-report … because I assume it is for a client and it is not 100 percent accurate. And I’ve never gotten anything from them that was 100 percent accurate. Not because they were slanting or lying or twisting. Every time I’ve gotten something from them, ’This is a report. You’ve got to check it out.’ I have a great relationship with those guys.”

During summer 2016, Fusion’s juicy tidbits enticed a number of elite journalists to heed Mr. Simpson’s call to meet Mr. Steele in person.

By then, Fusion had amassed a deep database on Mr. Trump, his contacts, his holdings and his deals.

“Fusion has filed a ton of [Freedom of Information Act] requests on Trump, especially in New York,” said the journalist source who asked not to be named and has had contact with the firm.

A Washington Times inquiry found that Mr. Simpson and crew were dishing out other supposed dirt on Mr. Trump and friends not contained in the 35-page dossier. Some of those tips have proved to be as shaky as Mr. Steele’s election collusion charges.

Besides the Jeffrey Epstein dump, Fusion pushed the story that a special email server existed between Trump Tower and Moscow’s Alfa bank, the journalist source said. The report has failed to catch on. Internet sleuths traced the IP address to a marketing spam server located outside Philadelphia.

Pre-dossier, readers rarely had seen Fusion’s hand in sourcing stories even though it may have instigated and framed scores of them over the years.

Fusion unmasked

Today, Fusion’s cover has been blown. It feels the sting of unwanted publicity in both the liberal and conservative press and intense scrutiny from Republicans on Capitol Hill. Senate and House committees demanded that Fusion produce representatives for hours of closed-door testimony.

Devin Nunes, California Republican and chairman of the House Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence, signed subpoenas forcing Fusion to disclose who pays it and whom it pays. His probe unmasked the Hillary Clinton campaign and the Democratic Party as dossier financiers.

Why such intense intrusion into a secretive opposition research firm?

The unmasking agent was Fusion’s own product: Mr. Steele’s dossier. It has proved to be so unfounded on its core collusion charges yet so influential in prompting investigations of the president that Republicans demanded to know its roots.

Those roots are: After Democrats paid Fusion through a middleman law firm, Mr. Simpson in June 2016 hired Mr. Steele with Clinton campaign cash. Mr. Steele in turn handed out money to unidentified Kremlin operatives who sullied Mr. Trump and associates.

As Mr. Steele churned out dossier chapters during the summer campaign, Mr. Simpson peddled them to Washington’s mightiest journalists.

Mr. Steele wrote in July, the month he briefed the FBI and it began its probe, of an “extensive conspiracy between Trump’s campaign team and the Kremlin.”

After the BuzzFeed posting, The New York Times outed the dossier duo of Fusion and Mr. Steele.

Democrats began to cite the dossier’s unconfirmed Trump charges at hearings and on TV.

As the charges remained unconfirmed into the spring, Republicans started focusing attention on a firm whose livelihood relies on a cloak of confidentiality.

Republicans, including Mr. Nunes and Senate Judiciary Committee Chairman Chuck Grassley of Iowa have been conducting investigations into how the dossier influenced the FBI to start one of the most important criminal investigations in U.S. history.

As Fusion fends off pursuers and gets ensnared in libel lawsuits against Mr. Steele and BuzzFeed, its costs are mounting.

Three Russian businessmen-bankers are suing Fusion for libel, creating a second legal front. Fusion is paying at least two law firms to fend off Mr. Nunes’ incursion in U.S. District Court.

“They’re under the weather because of their legal bills,” the journalist source said.

Part of Fusion’s defense is that it enjoys First Amendment rights just like its founders’ days at The Wall Street Journal.

Fusion jealously guards the list of its journalistic recipients and, in turn, is treated as a confidential source to the point that there are rarely Simpson fingerprints on its investigative products.

But the dossier’s disclosure broke the code of silence. In one of three libel lawsuits, Mr. Steele has been forced to explain how he and Fusion worked together.

In a court filing in London, he named names: In Washington in September, Mr. Steele met with The New York Times, The Washington Post, Yahoo News, The New Yorker and CNN — a who’s who of America’s liberal media establishment.

The next month, Mr. Steele said, he delivered a second briefing to The New York Times, The Washington Post and Yahoo News.

Before Mr. Steele’s D.C. visit, Fusion turned to old colleagues at The Wall Street Journal. In July, a reporter contacted Carter Page, a Trump campaign volunteer. Mr. Steele had spun a web of deceit and lawbreaking by Mr. Page on a trip he took to Moscow to deliver a public speech at a university.

The call blindsided Mr. Page, a New York energy investor who had no idea a dossier time bomb lay ready to destroy his life. The call also showed that Fusion can summon the top of Washington’s journalism food chain to run down its tips.

The Wall Street Journal did not run a story at that time. Mr. Page, who lived in Moscow in the 2000s and knows scores of Russians, said the dossier sections on him are fabrications.

Mr. Steele said he warned journalists that they must confirm his intelligence before reporting. Mr. Steele “understood that the information provided might be used for the purpose of further research, but would not be published or attributed,” his attorneys said.

Two journalists did write stories.

Yahoo News’ Michael Isikoff wrote of the charges against Mr. Page, attributing them not to the dossier but to a Western intelligence source. The story blazed across the internet and became red meat for Clinton campaign surrogates.

Mr. Page has filed a libel lawsuit against Yahoo News.

On Oct. 31, 2016, a second dossier story appeared, this one by David Corn in the left-leaning magazine Mother Jones. He is also a co-author with Mr. Isikoff of “Hubris,” a book on the Iraq War that is critical of former President George W. Bush.

Mr. Corn conducted perhaps the only published interview with Mr. Steele during the election campaign, though he hid the ex-spy’s identity as a “former senior intelligence officer.” The story refers to Fusion but not by name.

Mr. Steele’s quotes conveyed an energized source as he bragged about his ability to get the FBI to accept his memos beginning in early July and then starting an investigation into the Trump campaign.

The FBI has refused to publicly answer dossier questions. The Mother Jones story is among the best-known evidence that the bureau began investigating the Trump campaign based on a Democratic Party-financed scandal sheet that remains unconfirmed.

Epstein-Trump

In January 2016, as candidate Trump scrambled to stitch together a presidential campaign against 16 Republican opponents, Vice.com ran a story on his ties to Epstein, the billionaire sex offender who owns a Caribbean island called Little St. James.

Reporters have confirmed Mr. Clinton’s visits to the island aboard Epstein’s “Lolita Expres,” based on court records.

Mr. Trump’s ties to the fellow Florida billionaire appear to be more social — some dinner parties, two plane trips, and hanging out at Mr. Trump’s Mar-a-Lago resort in Palm Beach, Florida.

A woman filed a lawsuit saying Mr. Trump raped her when she was a teenage acquaintance of Epstein’s. “Jane Doe” dropped her lawsuit a few days before the election. Mr. Trump’s people vigorously denied the whole scenario.

Mr. Silverstein, who wrote the Vice.Com story, was asked by The Washington Times if Fusion pushed the Epstein-Trump story.

“Since you asked, yes, they helped me with that,” Mr. Silverstein said. “But as you can see, I could not make a strong case for Trump being super close to Epstein, so they could hardly have been thrilled with that story. [In my humble opinion], that was the best story written about Trump’s ties to Epstein, but I failed to nail him. Trump’s ties were mild compared to Bill Clinton’s.

“I said Fusion could not have been happy with the Epstein story,” he added. “What I mean is that I never proved a really sleazy connection, so frankly I was disappointed too, I thought there was more (and still wonder). But Fusion never pressured me to write anything untrue, and they never told me anything about ties between DT and JE that was false. That’s important. Their work has been solid if not 100 percent accurate in their reports, just as I periodically make mistakes. I have never seen malice or anything less than the best effort to be accurate.”

The fact-checking system also applies to the dossier.

“I don’t think anyone really nailed them because I don’t think they did anything wrong,” Mr. Silverstein said. “I think they were chasing money like all these firms do. Maybe they were chasing too hard. But I haven’t seen them breaking the law. … The reporters have to vet it and verify it. … A private intelligence firm working for a private client, you can’t assume you are getting something that is 100 percent accurate.”

Mr. Silverstein takes delight in taking the left and right to task.

In a Dec. 8 story in WashingtonBablyon.com, he wrote of the latest CNN goof: “Well, well, well. A central ’fact’ of the whole Russia-Trump collusion story turns out to be fake news. The original ’fact’ was reported by CNN, President Donald Trump’s favorite Fake News Network, so Trump is going to be popping corks on champagne bottles this weekend. Nice job, CNN!”

Romney and VanderSloot

Until the dossier’s splash, Fusion’s secrecy tradecraft was nearly watertight. Its sparse web home page is mostly white space around a two-paragraph mission statement and an “info” email address.

But a few leaks have happened, such as its investigations — some would say hit jobs — of big donors to Republican Mitt Romney in his 2012 bid to unseat President Obama.

The Obama campaign listed eight megadonors as bad people. One of them, Idaho businessman Frank VanderSloot, donated $1 million to a pro-Romney PAC.

The Wall Street Journal editorial page reported during the election that someone was rummaging through Mr. VanderSloot’s divorce files. The paper traced the operative to Fusion GPS. Mr. Simpson defended the dirt-gathering on grounds that Mr. VanderSloot’s wife contributed to a campaign against same-sex marriage.

Then there is Fusion’s own Russia connection. While Fusion is exposing supposed collusion between the Trump campaign and Russia, its operatives have been working for Russians to dishonor Bill Browder, a prominent opponent of President Vladimir Putin.

The web of connections is complex: Russian money is funding Fusion to destroy the reputation of Mr. Browder, a U.S.-British banker, for his work to persuade Congress to enact the 2012 Magnitsky Act. The act is a sanctions law against Moscow, and the Putin regime wants it repealed. Mr. Browder told the Senate Judiciary Committee that Fusion received Russian money via the law firm BakerHostetler to launch “a smear campaign against me.”

In another case, Fusion allowed Planned Parenthood to identify it as the firm that analyzed hours of secret video taken by the pro-life group Center for Medical Progress. The group said it captured Planned Parenthood leaders talking about selling fetal body parts.

Fusion issued a report saying the videos were not accurate. The pro-life group’s own analysis showed no manipulation.

The irony in all this is that Mr. Simpson once condemned smutty opposition research as a scourge on the body politic.

He co-wrote a 1996 book, “Dirty Little Secrets: The Persistence of Corruption in American Politics,” with celebrity University of Virginia politics professor Larry J. Sabato.

“Most opposition researchers claim to pay attention mostly to legislative votes and floor statements to see if their opponent’s words jibe with his or her record,” Mr. Simpson and Mr. Sabato said in quotes unearthed by RealClear Investigations. “Without question, many abide strictly by this unwritten code. Yet many of their brethren also examine highly personal information, with the result that issues often surface that are only marginally related, or even completely unrelated, to the office being contested.”

In an interview with C-SPAN’s Brian Lamb, Mr. Simpson bemoaned the use of “push polls” to spread unfounded rumors about candidates.

The “highly personal information” Mr. Simpson condemned 21 years ago certainly can be found in the salacious Trump dossier or his promotion of a Trump-Epstein alliance.

Mr. Simpson and Fusion did not reply to messages.

In a sense, the dossier was a failure in that Mr. Simpson could not persuade a large number of reporters to spread its smut during the election campaign. The dossier’s 35 pages ultimately subjected Fusion to an unwanted limelight, a congressional investigation and steep legal fees.

In January, The New York Times described the failure to confirm the dossier’s charges before Nov. 8.

“Fusion GPS and Mr. Steele shared the memos first with their clients, and later with the FBI and multiple journalists at The New York Times and elsewhere. … Many reporters from multiple news organizations tried to verify the claims in the memos but were unsuccessful.”

But in another sense, the dossier — with all its unproven and far-fetched tales — has been a political success for Trump haters.

It influenced the FBI to launch a counterintelligence investigation into the Trump campaign that has grown into a full-blown special counsel inquiry with nearly 20 prosecutors and scores of FBI agents.

The dossier created thousands of social media devotees who are convinced its felony charges against the president and his aides are true.

Back in London, Mr. Steele can take pleasure in a special counsel investigation that could dog the Trump White House, the president, and current and former aides for months, maybe years.

• Rowan Scarborough can be reached at rscarborough@washingtontimes.com.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.