OPINION:

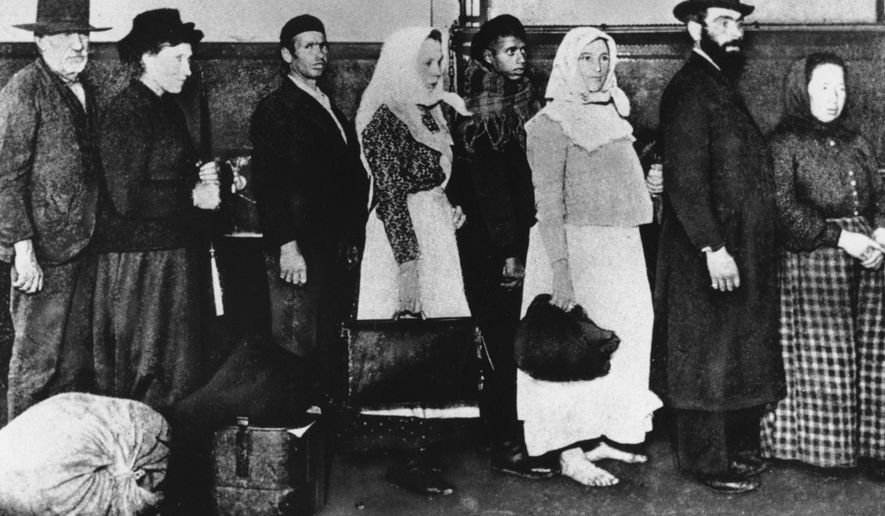

The little kid and his dad struggled to make heads or tails of what the Ellis Island customs agents were saying.

Those agents struggled just as hard, finally making “Hallow” out of “el-Hilou” — the family name the kid and his father were trying to convey. The kid would, much later, be my dad.

The 19th century had just turned into the 20th. My dad was 8 years old and had blessed himself, with thumb and two fingers together in the Syrian Orthodox manner, as the Statue of Liberty passed astern of the last of several vessels that had borne the two Hilous from Syria across the length of the Mediterranean Sea and the breadth of the Atlantic Ocean. Dad came fully equipped with a third-grade education — in Arabic. English was Greek to him.

My mother had a similar Ellis Island arrival from Syria with her parents when she was 3 years old.

Eventually Dad and Mom met, married and had me. That made me a native-born American with a privileged citizenship I cherish all the more for knowing that timing is everything. A few years after my parents’ arrival, immigration law tightened enough to keep out the likes of my parents. Time passed and the laws opened up again.

Soon you may hear the grinding of our immigration doors as they narrow the opening for newcomers. Two Republican senators have introduced a bill to move to the front of the line those foreigners with qualifications not possessed by my mom and dad or by their parents.

If you can flash a college diploma, boast a skill that promotes our national interests, mouth English with credible clarity and have a job awaiting you in, say, Cleveland, immigration officials will greet you with thumbs up and a smile. George W. Bush tried to add merit as an immigration criterion in 2007.

President Trump likes the current effort bill.

I should hate it. I don’t.

My father and mother loved America because, in their minds, it provided the greatest opportunity on earth. They loved that America aspired to believe in the ultimate worth of the individual. That is huge in the history of ideas. Each and every individual is worth more than the society as a whole. This was, and is, a crucial distinction from other cultures and explains American exceptionalism.

You could argue — I will, if you won’t — that “rugged individualism” is the ultimate antidote to the totalitarianism that professional race-baiters and white-privilege hysterics claim to see behind every Bush and Trump tee.

Call it “communism,” “fascism,” “statism” — totalitarianism is the practical application of the notion that a government may govern without the consent of the governed.

The “ultimate worth of the individual” antidote is in America’s blood because the people who settled the colonies came from that handful of societies on the planet — Britain foremost among them — that had developed but not fully implemented such views. That’s not nativism or ethnocentrism but a simple fact of history.

John Adams, Benjamin Franklin Thomas Jefferson, Alexander Hamilton (born on one of Britain’s Caribbean island-colonies), James Madison, George Washington and their crew were uniquely equipped to hold and institutionalize ultimate worth, along with freedom of speech, association, religion and the rest. And they were able to start fresh, their new nation unencumbered by a history of divine monarchy.

After the colonies united, they experienced the arrivals, in bursts and trickles, of new people, some of whom came from societies unacquainted with the ultimate worth of the individual, governance by consent of the governed and the freedoms enumerated in our Constitution.

They came seeking economic opportunity and freedom, religious and otherwise — a concept little known outside of Western Europe in America’s early days. Newcomers from countries hostile to, or ignorant of, these freedoms learned them through assimilation — that certain something that gradually turns you from being Syrian, Serbian, Japanese, Chinese, Nigerian or whatever into thinking of yourself as American and therefore of ultimate worth as an individual and willing and eager to defend the right of your neighbor to disagree with you and your religion.

Immigrants unschooled in personal freedom, tolerance, the rule of law and English (a single language being any nation’s crucial binding agent) were too few in numbers to avoid at least some interaction with, and influence from, the broader society.

Besides, Pilgrim, if you didn’t learn English, you’d have a harder time earning money to put food on the table and a roof over your head.

But something’s giving the willies to many descendants of foreign-born parents here. There’s this creeping concern, like a tooth just beginning to loosen, that too many newcomers from cultures hostile to the ideas of Adam Smith and John Locke may be impeding or crippling assimilation. Same for the feared (though unproven) effect of automated telephone greetings and answering messages in multiple languages, TV channels in multiple languages, public school classes in multiple languages.

When you throw down the welcome mat for more unskilled or underskilled newcomers to an American economy insatiably hungry for the most highly skilled workers, you may impede improvement in living standards for all but the fabulously rich. No, that’s not a scientific fact, but it is a legitimate concern.

I want what is likely to best preserve American exceptionalism in every one of its aspects. I think that means for now a shift in immigration priorities and cutting in half the total legal immigration allowed.

The priorities now favor relatives — regardless of skill, education and language — of people who are already here and who may or may not be assimilated. The new priorities should smile for now on hotshot physicists and computer supertechies with an audible grasp of English.

Yes, this shift would have kept my parents in Syria, where they did not have a God-given right to emigrate to the U.S. No foreigner anywhere does. Rather, the people of the United States, through their elected representatives, have a God-given right to determine who gets to come across our borders and what we want them to contribute.

You get a shot at remaining in the shining city on the hill by keeping the lights burning.

⦁ Ralph Z. Hallow, the chief political correspondent of commentary, served on the Chicago Tribune, Pittsburgh Post-Gazette and Washington Times editorial boards, was Ford Foundation Fellow in Urban Journalism at Northwestern University and resident at Columbia University Editorial-Page Editors Seminar.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.