OPINION:

“The Middle East is the graveyard of predictions” notes the left-wing writer and editor Adam Shatz. That’s partly because it’s so volatile (no one in 2014 imagined the revival of an executive caliphate after 11 centuries) and it’s perverse (Turkey’s President Recep Tayyip Erdogan started a near-civil war against the Kurds to win constitutional powers he already enjoys).

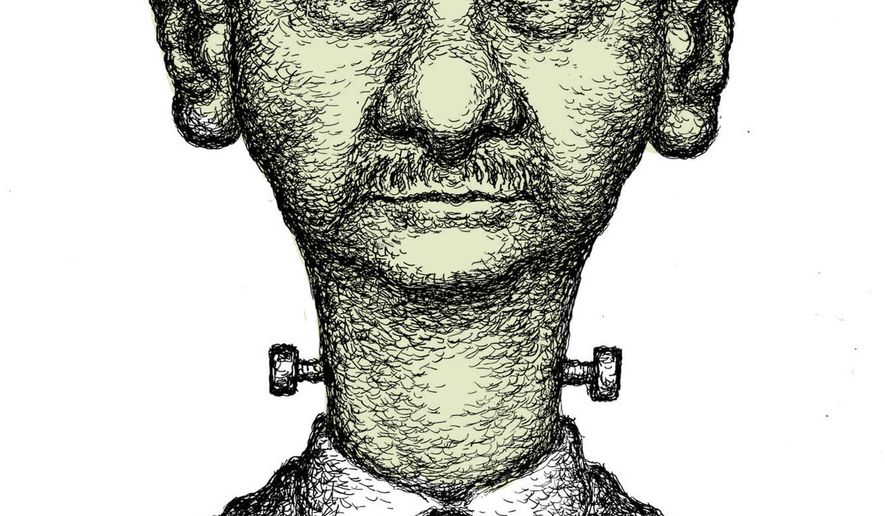

In part, too, predictions fail because of the general incompetence of the specialists in the field. Too often, they lack the common sense to see what should be self-evident. Case in point: the collective swoon upon the accession of Bashar Assad to the presidency of Syria in 2000.

Some analysts of Syrian politics expressed skepticism about a 34-year-old ophthalmologist’s ability to manage the “desolate, repressive stability” that he inherited from his dictatorial father, who had ruled for 30 years. They suggested that the “deep tensions in Syrian society could explode after the long-time dictator’s demise.”

But most observers divined in the young Mr. Assad a decent fellow if not a closet humanitarian. David W. Lesch, an academic who rejoices in the title of Ewing Halsell Distinguished Professor of Middle East History at Trinity University in San Antonio, Texas, led this particular pack. Mr. Lesch befriended the young strongman, enjoying what his publisher calls “unique and extraordinary access to Syria’s president, his circle, and his family.”

Those long hours of conversation led to a 2005 book, “The New Lion of Damascus: Bashar al-Asad and Modern Syria” (Yale University Press) plus a cascade of praise from fellow academics: Moshe Ma’oz of the Hebrew University found it “very informative and perceptive.” Curtis Ryan of Appalachian State University called it “revealing.” James L. Gelvin of UCLA praised it as “an extraordinarily readable and timely account.” A prestigious Washington think tank hosted a discussion of the book’s findings.

But the passage of a dozen years, half of them consumed by Mr. Assad’s monstrous brutality in the region’s most lethal civil war of modern times, provides a very different perspective from which to gauge Mr. Lesch’s scholarship.

Mr. Assad responded to the peaceful demonstrations against his regime that began in March 2011 not with reforms but with vicious force. The total number of dead is about 450,000 out of a pre-war population of 21 million. Mr. Assad’s personal barbarism has throughout been the key to this conflict. For example, exploiting his control of the skies, Mr. Assad’s troops have perpetrated an estimated 90 percent of the war’s fatalities.

According to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, more than 5 million Syrians have been internally displaced and about 6.3 million have fled the country. Their large numbers have caused crises in such disparate countries as Jordan, Lebanon, Turkey, Greece, Hungary, Germany and Sweden.

In light of this appalling record, Mr. Lesch’s account contains many passages of extreme gullibility and poor judgment. He assessed Mr. Assad roughly as he might a university colleague, deploying such adjectives as “compassionate,” “principled,” “unassuming,” “innocent” and “morally sound.” He described Mr. Assad as “a man of great personal integrity” with “appealing sincerity” with “a vision for the future of his country.” He tells us that those who meet Mr. Assad are struck by “his politeness, his humility, and his simplicity.” Turned around, “The thuggish behavior that was associated with his father is not in Bashar’s character.”

On the private level too, Mr. Assad is an exemplar: “He changes diapers, gets up in the middle of the night to calm a crying child. During the entire first year of [his son’s] life, Bashar did not once miss giving him his daily bath.”

He’s also a cool cultural figure for Westerners: “As well as liking music by Phil Collins, he enjoys Kenny G., Vangelis, Yanni, some classical pieces, and 1970s Arab music. He loves classic rock, including the Beatles, Supertramp, and the Eagles, and he has every album by the Electric Light Orchestra.”

As for his wife Asma, she “certainly seems to share her husband’s calling to do everything in his power to make Syria a better place for their children and grandchildren.”

To his credit, Mr. Lesch recognizes the possibility of an implosion, “with regime instability leading to a potential civil war.” But he rejects this scenario because “The opposition to the regime within Syria is divided and relatively weak.”

Not surprisingly, “New Lion,” a monument of scholarly humiliation, has gone out of print and has vanished from Yale University Press’ website.

• Daniel Pipes is president of the Middle East Forum.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.