Ask D.C. Delegate Eleanor Holmes Norton what “affordable housing” means, and she will quickly tell you, “There isn’t any.”

But give her a minute, and she will explain that any housing poor people can afford in the District is diminishing rapidly — and soon will be gone because of gentrification.

“I just think that is one of the great dilemmas of American society. I don’t think it has been solved,” Ms. Norton said at a recent job fair she hosted in Northwest. “I’m not sure how you solve this dilemma. And I have never heard of anyone who had” a solution.

In a growing city where homes sell for millions of dollars and rents for downtown apartments can range from $1,500 to $15,000 a month, determining what constitutes “affordable housing” can depend on whom you ask and where you look.

The District’s overall median home value is $551,300, but the median for Ward 3 is $823,800 and for Ward 8 is $229,900, according to 2015 U.S. census estimates at CensusReporter.org.

Still, Ms. Norton, the District’s nonvoting representative in Congress, paints a bleak picture of affordable housing, which D.C. Mayor Muriel Bowser has made a hallmark of her agenda. Miss Bowser’s office notes the delivery of 3,937 affordable units since January 2015.

“The mayor is working for our families by being the first mayor to invest $100 million annually into the Housing Production Trust Fund — which is more than any city per capita in the country,” Bowser spokeswoman Latoya Foster said in an email. “In 2016 alone, we invested $106.3 million towards 19 projects that will produce or preserve more than 1,200 affordable housing units. We will not waver from our commitment to create and preserve affordable housing.”

Indeed, the D.C. government has provided, and is providing, affordable housing units in each of the city’s eight wards.

But affordable units in Wards 7 and 8, the city’s poorest, are more densely packed than those in other wards, especially those in the western part of the District.

Wards 1 and 2, respectively, host 11 and 16 affordable units per housing development, while Ward 7 has 44 and Ward 8 has 54 such units per development, according to data from the Economic Intelligence Dashboard on the D.C. government’s website.

“You will find that the farther east you go, the more affordable housing there is because they haven’t been gentrified yet,” Ms. Norton said.

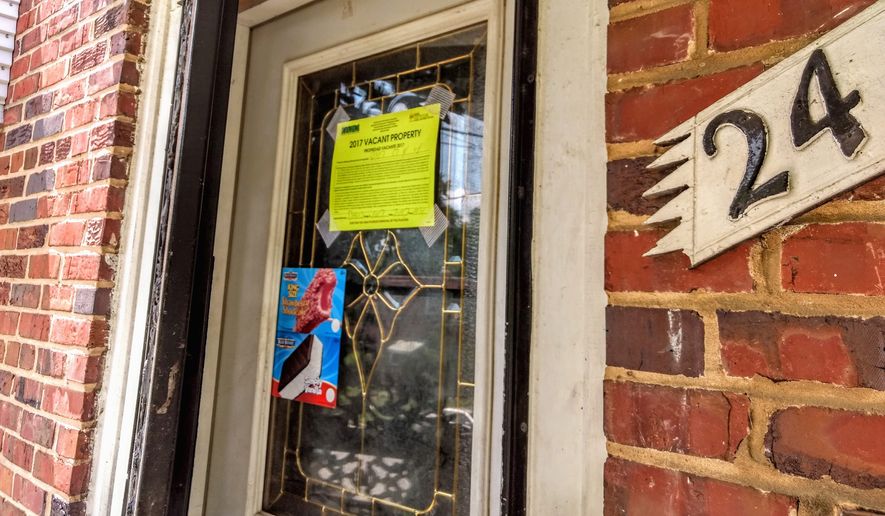

Neglected, run-down sections of the city are ripe for redevelopment, which attracts retail and other commercial interests. As once-abandoned buildings are refurbished and hard-hit communities are renewed, rents and mortgages rise along with property values.

And as property values rise, so do property taxes — and suddenly longtime residents find themselves unable to afford the homes where they have lived for years.

The District’s median home value has risen about 46 percent over the past six years, from $376,000 in 2012 to $551,000 in 2017, according to the real estate website Zillow.com. The median is expected to rise 1.9 percent next year, to $561,000.

Meanwhile, the city’s median annual income is $75,728, up from $67,000 in 2012. But the median income in Ward 3 is $112,873, while that in Ward 8 is only $30,910, according to 2015 U.S. census estimates at CensusReporter.org.

What is considered affordable apparently would vary from ward to ward. It’s something the D.C. Department of Housing and Community Development must contend with.

“We have a policy: When we dispose of our land and it’s residential 30 percent of the units produced have to be affordable, 75 percent of them have to be at 50 percent of the area median income and 25 percent of them have to be at 30 percent AMI,” a city official told The Times on background.

’Eye of the beholder’

The area median income for the greater D.C. region, which includes the Virginia and Maryland suburbs, is $109,200 for a family of four. Thirty percent of the area median income is $32,760 — $1,850 more than the median income for Ward 8.

Claire Zippel, a policy analyst from the D.C. Fiscal Policy Institute, told The Times that a large number of low-income residents remain underserved by the District’s affordable housing initiatives.

“Only a very small portion, around 15 percent of the new rental units that the city has created, has been available to folks who make under 30 percent of the area’s median income,” said Ms. Zippel.

“People making around minimum wage can afford around, say, $800 a month. A lot of the new apartments the city is subsidizing are maybe $1,100 a month. So that’s obviously out of reach of the typical minimum-wage worker or someone who relies on Social Security or disability payments,” she said. “And these are the folks who not only are most likely to be homeless, but are more likely to have to leave the city.”

The District’s $11.50-an-hour minimum wage amounts to about $24,000 a year.

According to the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, people who spend more than 30 percent of their income on housing are officially considered cost-burdened and are eligible for vouchers and other government programs.

But Leah Brooks, an economist and public policy professor at George Washington University, said the 30 percent rule is not one-size-fits-all.

“I think it is true that Americans have been spending gradually larger and larger fractions of their incomes on housing over time. So what the right number is is just not obvious,” said Ms. Brooks. “Really, affordable housing is in the eye of the beholder.”

The proposed creation of affordable housing at the Barry Farm public housing complex in Southeast provides an interesting look at the tensions redevelopment can bring. The D.C. Housing Authority is moving forward with plans that will require 513 residents to leave their homes for temporary shelter before construction can begin, promising them they can return if they choose.

The current 432-unit housing complex is to become a mixed-income property with 1,400 new units. Of those, 344 units will be set aside for residents whose income is 30 percent of the AMI or lower — the federal definition of “affordable.” A total of 918 units (including the 344) will be set aside for residents whose income is 80 percent of the AMI or lower — the District’s definition of “affordable.”

Some Barry Farm residents are refusing to leave because they are not confident that they will be able to return after the redevelopment. Paulette Matthews is part of Occupy Barry Farm, which demands that reconstruction on the complex begin while residents stay in their homes.

“It’s about property, it’s about reclaiming stuff, it’s about having control over people,” Ms. Matthews told WAMU about the $13 million project.

Expectations

The D.C. government has responded to the concerns of displaced residents by implementing the Tenant Opportunity to Purchase Act, which helps tenants buy the properties they live in if their landlords decide to sell them.

The Office of the Deputy Mayor for Community and Economic Development grants public land to builders who include a certain percentage of affordable units in new developments.

Ms. Norton said Miss Bowser’s efforts to create more affordable housing will “take a small slice out of it [but] in terms of the kinds of housing in the District of Columbia that’s affordable that is not available.

“Affordable housing means if you’re making a good deal of money. For example, in some of the projects I’ve even brought to the District — that’s going to be all kinds of housing,” the congressional delegate said. “But I wouldn’t dare use the words ’affordable housing’ on it.”

Ms. Zippel said gentrification is only going to advance through the District.

“We’re going to continue to see neighborhood after neighborhood be transformed in a way that leaves poor residents and residents of color behind and pushes them out of their communities,” she said. “That’s not the kind of city that I think most D.C. residents want to live in.”

David Meadows, a spokesman for at-large D.C. Council member Anita Bonds, said lower-income residents ought to grab any housing they find that they can afford.

“Everyone has their own definition, but the problem is when housing becomes nonexistent for a large part of your population,” Mr. Meadows told The Times. “In D.C., you’re finding that 50 [percent to] 60 percent of income is being spent on housing alone, which leaves no money for health care and other needed services. If they can find something at 20 percent of their income, get it.”

D.C. officials maintain that affordable housing can be found anywhere in the city. But one official, who spoke on background, said lower-income residents simply have to adjust to what’s available.

“Part of the process is measuring expectations,” the official said. “Everyone has that individual journey as far as measuring their expectations. The job of the government is to provide options even if they still have to make trade-offs. We all have to do that.”

Nonetheless, Ms. Norton said the future of affordable housing’s promised expansion isn’t bright.

“D.C. is doing some good work here, but the notion of expanding affordable housing, particularly in relation to the housing that’s going up and is being built, is just not happening. I don’t expect it to happen,” she said. “We shouldn’t pretend that we know what the answer is.”

Please read our comment policy before commenting.