OPINION:

It appears to be accepted that North Korea will have an intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) capability with a suitably miniaturized warhead in the next three to four years, along with the capacity to deliver that weapon to the West Coast of the United States.

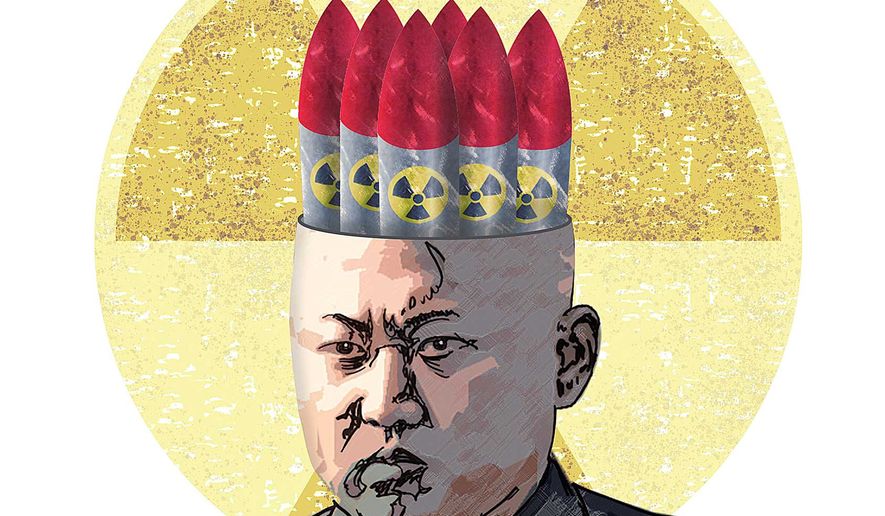

Pyongyang has already announced it is prepared to take any action necessary to “deter U.S. aggression.” At this point, the only apparent non-military action to stop or impede such an evolution is Beijing’s diplomatic intervention with the leader of North Korea. However, the recognized unstable character of leader Kim Jong-un makes even such a seemingly influential entreaty relatively unenforceable no matter the degree of pressure Beijing places on Pyongyang. Thus, barring a complete reversal of Mr. Kim’s current behavior, the United States must plan to destroy North Korea’s nuclear and long-range missile sites sometime in the next several years — and perhaps within the next two.

At the same time, it must be expected that the American action would trigger the North Korean military to instinctively launch a full-scale retaliatory strike against the Republic of Korea (ROK) along the armistice line of the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ), whether or not Mr. Kim remains alive. With that as a given, the United States must prevent such an event by launching, simultaneously with the initial attack on the North Korean nuclear and ICBM facilities, a full-scale offensive against the North’s positions along the DMZ. There can be no delay in this U.S.-ROK offense, for it is essential to preclude North Korea’s own counteroffensive against the South.

Currently, there is a hopeful analytical view that Mr. Kim is using his well-announced nuclear program simply as a defensive device to deter any attempt to threaten Pyongyang into actions counter to his interest in maintaining dominance over his nation. In other words, Mr. Kim is merely seeking to prevent an attack rather than preparing to attack. That reasoning certainly hasn’t been his motivation for executing scores of ranking officers and political personalities who tended to disagree with him, including his uncle-in-law, originally thought of as his mentor.

Hopes that the Chinese will have greater success through promises or threats to deter Mr. Kim’s ambitions seem to fly in the face of reality. The last time Beijing tried to alter his desires was in 2013 when Beijing sent Vice Foreign Minister Fu Ying to Pyongyang to talk the clearly unstable leader out of launching a satellite. The result was a very swift and undiplomatic rebuff that sent the Chinese official unceremoniously packing.

For any strategic planner to count on a reasoned approach from Mr. Kim motivated by a commitment to a posture of deterrence lacks logic. Ultimately, such an analysis is a bet that any experienced opponent simply could not afford to take. If President Trump had as good an exchange with China’s President Xi Jinping as has been reported, this was certainly communicated, as was any commitment by the Chinese leader to give the desired effort to restrain Mr. Kim the “old college try.”

Equally, it did not have to be explicitly stated that the United States would have no alternative but to take the necessary action to “inhibit” the North Korean leader’s eventual ability to launch a nuclear attack on the American West Coast. Beijing is both highly strategic and pragmatic in its thinking. The Chinese know what the future holds if Mr. Kim is not restrained. There may be slightly more than a couple of years left to await final action — but not much more. China knows that, and so do the Russians. One can only hope the Western Alliance members are also that realistic. Unfortunately, it appears the American press and public do not seem to be as aware as the situation demands.

• George H. Wittman has spent 45 years in operations and analysis in the field of international security affairs.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.