Civil liberties advocates and federal prosecutors will face off Tuesday in the D.C. Court of Appeals over the city police department’s warrantless use of secret cellphone tracking technology to locate a sexual assault suspect.

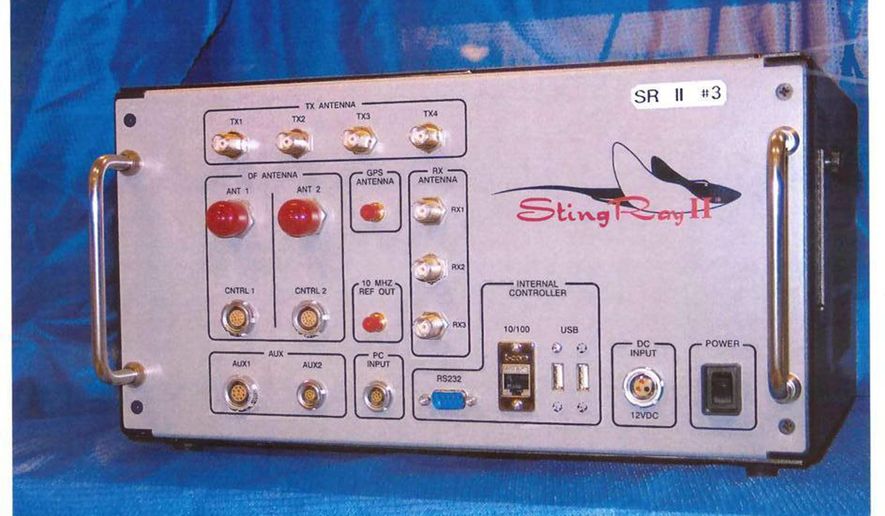

The case represents the first time the Metropolitan Police Department’s use of the technology, a cell site simulator known by the brand name Stingray, has been challenged at the appellate level. The case has attracted the attention of the American Civil Liberties Union and the Electronic Frontier Foundation — groups waging legal battles nationwide to rein in law enforcement agencies’ use of such surveillance.

Defense attorneys have appealed the robbery and sexual assault convictions of Prince Jones, arguing that the police department violated his Fourth Amendment privacy rights by deploying a Stingray to track cellphones in his possession and ultimately to locate and arrest him.

Prosecutors from the U.S. attorney’s office for the District of Columbia say it was unclear whether the technology was used to track Jones’ cellphone or a cellphone taken from one of the victims — in which case Jones’ claims to privacy violations would no longer be relevant.

But they argue in briefs filed in the case that even if police tracked Jones’ phone, they still could have located him by tracking the victims’ phone. They also note that when officers zeroed in on Jones, he was on a public street and not in a home, where privacy protections might have come into play.

Privacy advocates began unearthing use of the surveillance technology by local police departments over the past few years, but since then only a handful of appellate courts have had the chance to weigh in on Stingray use by law enforcement.

A D.C. Court of Appeals ruling on the case wouldn’t be binding outside of the nation’s capital, but it will carry influence when other courts consider similar issues, said ACLU attorney Nathan Wessler, who will present arguments Tuesday against warrantless use of cell-site simulators.

The devices work by mimicking cell towers to trick cellphones to connect to them, enabling investigators to obtain identifying information about the phones and their precise locations. Under nondisclosure agreements with federal law enforcement, local police departments in possession of such technology have fought to keep secret their use of the equipment — even going to the extreme of dropping charges to avoid disclosing their use.

The D.C. Public Defenders Service, which is representing Jones, notes in its brief that in the time since the appeal was filed, two other courts “have held that the Fourth Amendment requires the government to get a warrant before using a cell site simulator to track a person’s location.”

The Maryland Court of Special Appeals ruled last year that police must establish probable cause and get a warrant before using cell-site simulators. Meanwhile, a Manhattan-based federal judge ordered that evidence be barred from a case in which the Drug Enforcement Administration failed to get a warrant before using a Stingray to track a phone to the apartment of a suspected drug dealer.

Jones was sentenced to 66 years in prison in 2014 after he was convicted of sexually assaulting two women who were contacted for escort services through Backpage.com.

MPD first began tracking his whereabouts by retrieving the phone number used to call the women from the escort ads, who were forced at knifepoint to perform oral sex and then robbed of their belongings. Court records indicate that investigators used data supplied by telephone companies to ping the phone as well as one of the victim’s stolen phones, and discovered that they were in the same general area near the Minnesota Avenue Metro station in Northeast.

Police deployed a cell-site simulator to pinpoint the exact location of the phones, but officers said during Jones’ trial in a lower court that they could not recall which cellphone was tracked by the device. The simulator eventually zeroed in on Jones, whom officers found sitting in his car with his girlfriend outside the Metro station. After officers stopped Jones, they found in his possession the phone used to contact the women, their stolen cellphones and a folding knife.

Prosecutors argue that rulings by the Maryland and New York courts are not relevant to the Jones case because they both involved tracking of cellphones inside defendants’ homes.

“The simulator revealed appellant’s location in plain view on a public street,” prosecutors wrote in their brief filed in the case. “Accordingly, the police did not obtain any information pertaining to the private contents of appellant’s home, or any other area as to which appellant had a reasonable expectation of privacy.”

The Public Defenders Service states that the issue came up in the Maryland case and that the court “concluded that because police cannot know in advance whether the target phone is in a public or private space, the only workable rule is a bright-line requirement that police must obtain a warrant every time a cell site simulator is used.”

Prosecutors pushed back against claims this type of surveillance is a violation of the Fourth Amendment, arguing that the police department’s use of a cell-site simulator does not amount to what the Supreme Court has defined as “trespassory search” of constitutionally protected areas including people, houses, papers and effects.

They argued that using the technology to find the phone “did not violate appellant’s reasonable expectation of privacy” in part because cellphone users have no expectation of privacy when their phones are on and are transmitting signals and location data to wireless companies and cell towers.

Mr. Wessler said the argument runs contrary to cellphone users’ assumption that they are not consenting to have their movements tracked by the government just because they carry cellphones.

Given the large number of bystanders, whose cellphone information is also swept up when law enforcement deploys Stingrays, Mr. Wessler said judicial oversight should be required.

Though some states have mandated that law enforcement obtain warrants before using the technology, and Justice Department guidance now indicates that federal law enforcement agencies obtain warrants in most cases, it is unclear what policies guide the vast majority of departments’ use of the technology, Mr. Wessler said.

“There has been some steady movement for greater protection but the kind of patchwork nature of the protections speaks to the need for Congress to step in and for courts to address the issue,” he said.

The three-judge panel hearing the case Tuesday is comprised of Judge Corinne Beckwith, an appointee of President Obama; Judge Phyllis D. Thompson, an appointee of President George W. Bush; and Judge Michael William Farrell, an appointee of President George H.W. Bush.

• Andrea Noble can be reached at anoble@washingtontimes.com.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.