OPINION:

Given our current strategy, many have understandably criticized the idea of doing more to address the war in Syria. For the United States, many of the options on the table — no-fly zones, arming insurgents, stepping up the use of American commandos — promise only gradual and partial battlefield gains. They hardly seem adequate to the task of achieving stated U.S. goals: simultaneously defeating the Islamic State, or ISIS, while displacing President Bashar Assad in favor of a multisectarian government of national unity. Given the risks of quagmire, and of direct U.S.-Russia conflict, a minimalist approach in which the United States contents itself with gradually weakening ISIS may seem the best option.

Yet this approach is also too cynical for a war that now rivals the lethality of Rwanda’s genocide and dwarfs the ethnic cleansing operations of the Balkans wars of the 1990s. It ignores the fact that defeating ISIS in Syria without a credible plan for addressing the civil war may simply fail. Or, even if it succeeds at first, it may leave in place the kinds of sectarian divisions that allow a successor movement to arise in the future. Implicitly, it probably assumes that Mr. Assad will largely win the war and remain in power in Syria. But he can never again be a stable and stabilizing leader for that country, given the brutality he has orchestrated since 2011 and the hatred he has engendered throughout the Sunni Arab world. This minimalist approach also demonstrates far too much insouciance about the stability of key regional friends and allies like Turkey, Jordan and Lebanon. It assumes that the extreme refugee crisis of 2015 that did so much to destabilize Europe and contribute to phenomena like Brexit is somehow permanently solved just because refugees are further from today’s headlines.

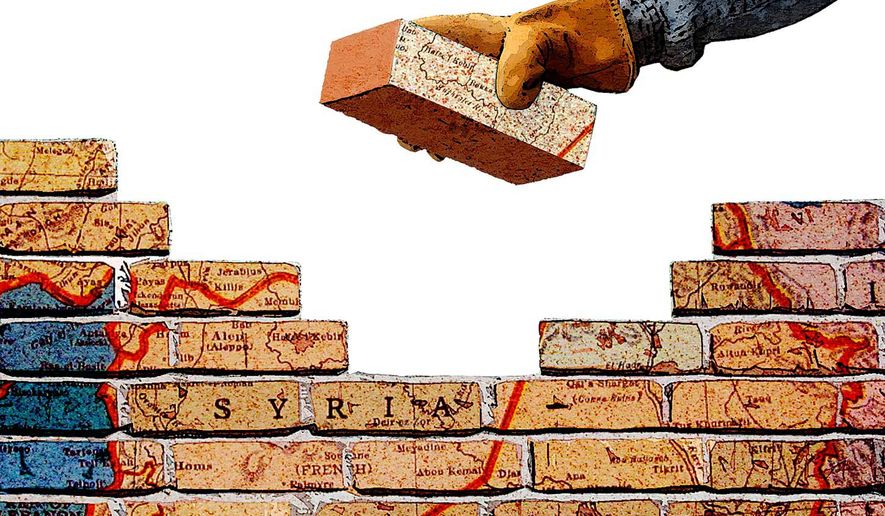

Fortunately, there is a plausible path out of this conundrum. Rather than try to stitch Humpty Dumpty back together again, rather than aim for a strong successor central government in Syria once Mr. Assad is somehow magically displaced, it recognizes that the Syria we once knew is gone — at least for now. It aims for a Bosnia-like confederation, but perhaps with a half-dozen autonomous zones rather than just three, each with its own government, local security forces and economic reconstruction plans. A new central government would have limited and largely diplomatic roles. This approach would still require the defeat of ISIS, but could tolerate Mr. Assad remaining in charge of one sector of the country predominately inhabited by his fellow Alawites and Christians.

A number of other scholars and practitioners have come to a similar conclusion about Syria. Yet the critics of a confederal concept for the country are legion. To be sure, the practical challenges associated with negotiating and implementing a Syrian confederation are considerable. But in fact, each can be addressed. Given the impracticality of any solution for Syria that does not devolve power from the center, it is important to do so. Consider these counterarguments to the critics of confederation:

• Confederation can work. Some point to Bosnia and Kosovo today and claim that their economic and political troubles prove confederation doesn’t make sense, in the Balkans or anywhere. But the latter missions, for all their flaws and their inability to date to foster true reconciliation across sectarian lines, have been unmitigated successes at keeping the peace.

• Confederation can protect minority rights. As Ed Joseph and I showed in a lengthy paper in 2007 about Iraq, there are mechanisms to protect minority rights in any negotiated deal setting up confederation. The latter need not, indeed cannot, create “pure” zones of just one ethnicity or confessional group. Governments, as well as the police forces and courts of the various autonomous regions, should be multi-ethnic in character.

• Confederation can reconcile core Russian and American interests. Moscow’s commitment to Syria is now so strong that it will be difficult simply to defeat Russian interests there. However, Russia’s core interests — retaining access to its port at Tartus, its airfield at Latakia, its promise of loyalty to long-standing friends in the Syrian regime, its desire to defeat ISIS and al-Nusra and other extremists — are all compatible with confederation. Arguably, they are better served by confederation than pursuit of complete victory for Mr. Assad, because the latter is almost surely impossible (even if neither Moscow nor Damascus has fully realized that fact yet). Indeed, Russian forces could remain in a peacekeeping role in Alawite-Christian sectors of the country under such an approach.

• Turkey may well ultimately support confederation. Many believe that Turkey, with its adamant opposition to anything trending toward Kurdish independence, would never tolerate a confederal model in Syria. But Kurdish populations could be divided into two zones, divided as they are today by a Turkish military presence (as part of a future peacekeeping force), to impede any such Kurdish aims. Moreover, the spigot of international development aid and other economic incentives could be conditioned on Kurdish compliance with the understanding that Kurds in Syria would never seek independence.

• Confederation is viable even for Syria’s mixed central cities. Under any confederal model, some cities such as Aleppo would have to be divided into two parts, or perhaps governed as single special multisectarian zones.

• Confederation is enforceable. Any negotiated confederation for Syria would require the deployment of international peacekeepers. These forces would monitor and locally uphold the terms of any deal, and help ensure the safety of those who wish to sell their property and relocate their families to a different part of the country. Such a mission would, to be sure, be harder and more dangerous than those conducted for so many years in Bosnia and Kosovo. In Syria, any deal would face would-be spoilers. As such, the United States and other militarily powerful countries would need to be part of the mission. But American forces could concentrate on logistics, intelligence, communications, air operations and commando action against extremists — GIs would not have to patrol the streets of Aleppo or Damascus.

• Confederation in Syria need not be permanent. Recognizing that Syria as a strong unitary state is gone for now need not mean it is gone forever. A peace deal that allowed for confederation could build in a 10-year and 20-year review of the basic legal underpinnings of the confederal model, authorizing in advance a new constitutional convention at one of those future dates, which could consider re-establishing a stronger central government.

None of the above is easy. All of it would eventually require painstaking diplomacy — and before that, substantial U.S.-led security efforts to change the balance of battlefield forces so Mr. Assad and Russia will see the need for reasonable compromise. So we need to get after this plan soon. There probably is no other viable choice.

• Michael O’Hanlon, senior fellow at Brookings, is author of the new study, “Deconstructing Syria.”

Please read our comment policy before commenting.