SANTA MONICA, Calif. (AP) - During more than 50 years in the public eye, Tom Hayden went from firebrand college liberal to mainstream politician to elder political statesman. Through it all he remained the person he said he always wanted to be: someone dedicated to changing the world.

Hayden, who died Sunday following a long illness, was barely out of his teens and a student at the University of Michigan at Ann Arbor in the early 1960s when he came to national prominence as co-founder of the Students For a Democratic Society, a group critics at the time often dismissed as a band of rag-tag malcontents threatening the American way of life with their leftist ideas.

In the years that followed, he went on to take part in Civil Rights Freedom Rides through the South and helped organize the protests at the 1968 Democratic National Convention in Chicago that led to his and other members of the Chicago 7 being charged with, and eventually cleared of, inciting riots.

After that, he married actress Jane Fonda and ran for political office several times, serving 10 years in the California Assembly and eight more in the state Senate. He lectured frequently on politics and wrote 20 books, leading some of his contemporaries to brand him a sell-out who joined the mainstream culture.

But even as his hair turned white, he never escaped his past - or for that matter even tried very hard to.

As he wrote proudly in his memoir of forgoing an early opportunity at a career in journalism: “I didn’t want to report on the world; I wanted to change it.”

Like others who felt that way, he had come of age in America’s tumultuous 1960s, a decade of dissent marked by civil rights sit-ins, anti-war marches, the Chicago riots and scenes of kids being tear-gassed and clubbed on American campuses.

He spoke many times about the era that planted his name in the American consciousness as a radical firebrand, anti-Vietnam War protester and defendant in the Chicago 7 conspiracy trial.

“Rarely, if ever, in American history has a generation begun with higher ideals and experienced greater trauma than those who lived fully the short time from 1960 to 1968,” he wrote in his autobiography “Reunion.”

He did sometimes wish aloud that his early advocacy hadn’t alienated quite as many people as it did.

“I can’t get past that,” he said in 2008. “… I can be like 68 years old and I’m still trouble because (people are) thinking about something in Vietnam or they’re thinking about Jane Fonda.”

Less remembered were the books he wrote, the countless lectures, blog posts, the 100-plus legislative bills he shepherded to approval or his advocacy for the environment.

His story began in America’s heartland - Royal Oak, Michigan - where Thomas Emmet Hayden was born on Dec. 11, 1939, into a middle-class family. He attended the University of Michigan at Ann Arbor, a hotbed of student politics. It was there that he cast his lot with the counterculture movement.

He took up political causes, including the civil rights movement, wrote fiery editorials for the campus newspaper and contemplated a career in journalism. But upon graduation, he turned down a newspaper job in favor of trying to change the world.

In 1960, the year that he graduated, he was involved in formation of Students for a Democratic Society, then dedicated to desegregating the South. By 1962, he became one of the key authors of its landmark Port Huron Statement, a call to students on campuses everywhere to take up political protest.

“We are people of this generation, bred in at least modest comfort, housed now in universities, looking uncomfortably at the world we inherit,” began the statement, which outlined a plan for a revolutionary campus social movement.

Hayden was fond of comparing the student movement that followed to the American Revolution and the Civil War.

He went freedom riding for civil rights in the South and was beaten and briefly jailed in Mississippi and Georgia. He married a fellow activist, Sandra “Casey” Cason, and together they witnessed the violence of the battle against segregation.

Yearning for a more influential role, Hayden returned to Ann Arbor to work on the Port Huron Statement.

“I didn’t want to go from beating to beating, jail to jail,” he wrote. “… There was an entire generation to arouse, primarily about civil rights but also about the larger issues.”

The largest issue at the time was the Vietnam War. In 1965, Hayden made his first visit to what was then North Vietnam with an unauthorized delegation. In 1967, he returned to Hanoi with another group and was asked by North Vietnamese leaders to bring three prisoners of war back to the United States. With the prisoners suffering medical problems, the U.S. State Department thanked Hayden for his humanitarian action.

Firmly committed to the anti-war movement, Hayden participated in sit-ins at Columbia University, then began traveling the country to promote a rally in Chicago for the 1968 Democratic National Convention. It became a turning point in his life.

A single event galvanized him - the 1968 assassination of his friend, Sen. Robert F. Kennedy, in Los Angeles.

“I went from Robert Kennedy’s coffin into a very bleak and bitter political view,” Hayden recalled in an Associated Press interview in 1988. “I think it confirmed for me that there was no future and brought out a lurking belief that this was a really violent country and that I was headed into apocalyptic times.”

Police assaults on student demonstrators in Chicago seemed to confirm his belief. The violence resulted in the circus-like Chicago 7 trial.

“In 1968, I thought it was reasonable to anticipate a police state,” he recalled. “But in 1972, the people who were running the Democratic Party four years before were out and the people who were in the streets were in. In the next year, the people who wanted to put me in jail began the road to jail themselves with Watergate.”

“The radical pressure caused the reforms,” Hayden said. “But it’s fair to say the system reformed itself.”

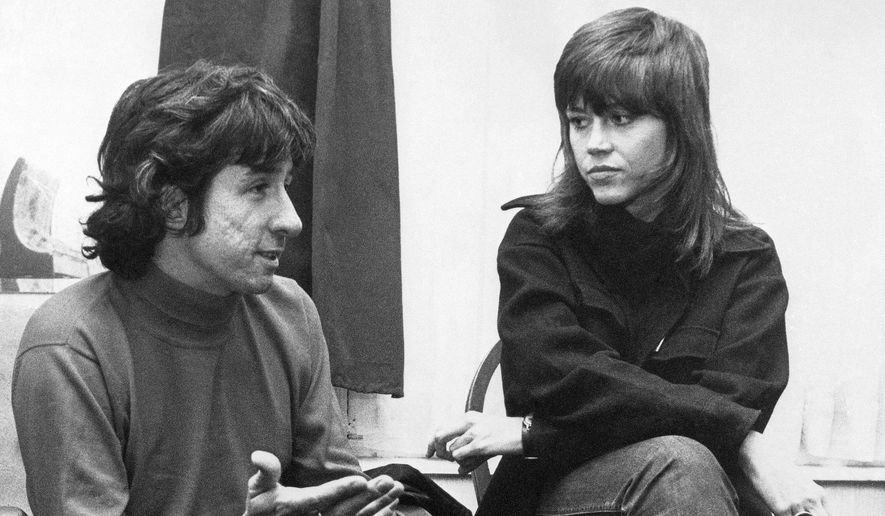

In 1971, Hayden met Jane Fonda who was a latecomer to the protest movement.

“She came from the orbits of fame, power and success. A popular actress and the daughter of Henry Fonda, she burst like a dislocated star onto the movement scene … but came only slowly and haltingly into my life,” he wrote.

After he heard her give an eloquent anti-war speech in 1972, Hayden said they connected and became a couple. He was divorced from Cason by then and Fonda was divorced from director Roger Vadim and had a daughter, Vanessa Vadim.

“I was 32, she 34, both of us were starting over,” he wrote. “The passion of our common involvement no doubt caused our involvement in passion for each other.”

He acknowledged ruefully that their marriage in 1973 may have appeared to some as “a remake of ’Beauty and the Beast.’ “

He was a rumpled longhaired activist who still cast himself as an outsider. She was a glamorous, world-famous movie star and heiress to a Hollywood dynasty. They were married for 17 years and had a son, Troy.

Both Hayden and Fonda were demonized by the political right after she visited North Vietnam in 1972 and was photographed posed on a North Vietnamese anti-aircraft gun. It took many decades to minimize her “Hanoi Jane” moniker.

Hayden once expressed regret about his past. In a 1986 piece he wrote for the Los Angeles Times, he said: “I regret most of all that I compounded the pain of many Americans who lost sons and loved ones in Vietnam. … I will always believe the Vietnam War was wrong. I will never again believe that I was always right.”

In the late 1970s, Hayden plunged into mainstream politics, winning election to the California Assembly. He also served in the state Senate before stepping down in 2000. He ran unsuccessfully for Los Angeles mayor and California governor.

In later years, he focused on writing, teaching and lecturing. Hayden married actress Barbara Williams, and they had a son, Liam.

He acknowledged contentment with his later life but confided that nothing would ever match the excitement of his early years.

“Whatever the future holds and as satisfying as my life is today,” he wrote, “I miss the ’60s and I always will.”

___

Deutsch is a retired AP special correspondent who contributed to this report. Hamada contributed from Phoenix.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.