The National Security Agency’s phone-snooping program ended six months ago this Saturday, but the government is still holding on to the mountain of data it piled up over the previous five years, worrying civil liberties advocates who say it’s time to start expunging the legally questionable information.

Government officials say they no longer access the information, but the intelligence community’s past behavior has some civil libertarians skeptical of those assurances. And the mere existence of the data, which includes the time, duration and numbers involved in phone calls, worries critics who say there’s no reason for it to be sitting under government control.

The intelligence community, though, says its hands are tied — chiefly by the very same advocates who are demanding that most of the data be expunged.

Some of those groups are helping pursue lawsuits seeking damages from the government’s snooping program, and courts have ordered all of the data to be preserved. That means the NSA can’t purge the information, even though it says it wants to.

“We take seriously the public’s concerns about the government’s retention of bulk telephony metadata collected under the now-terminated bulk metadata program,” said Timothy Barrett, spokesman for the Office of the Director of National Intelligence. “Retention of this data is necessary to comply with preservation obligations in civil litigation challenging that program, including court orders entered in two of those cases.”

The phone records program began under President George W. Bush and was kept in place by President Obama, based on powers claimed under the Patriot Act’s “business records” provision. The NSA demanded that phone companies turn over their records of calls, which were then stored in government databanks for five years.

Analysts queried the data when they had a number they believed associated with terrorism, and could pursue up to three “hops,” meaning they could see check numbers associated with the initial lead, all the numbers associated with that set and then all the numbers associated with the second set.

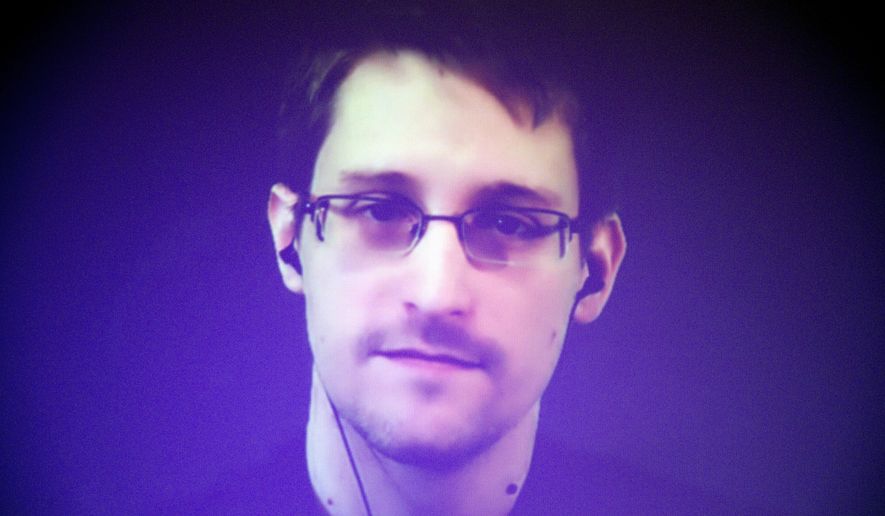

Former government contractor Edward Snowden revealed the program’s existence in 2013, spawning a massive public backlash that forced Congress to curtail the program. Lawmakers passed the USA Freedom Act last year, giving the NSA 180 days to shut down its own database and instead rely on private companies to keep the data, which the government could query under more strict circumstances.

The program expired on Nov. 28, and the government was to dispose of its data.

But the administration got an order from the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court allowing it to preserve all of the data, arguing that the government needs it to fight the 10 court cases challenging the defunct program.

The Electronic Frontier Foundation, which is assisting the plaintiffs in several of the key cases, said the government should find a way to get rid of most of the data.

“Talks are continuing about a plan under which the government would destroy the phone records — including those still lingering in its various databases — while ensuring that the courts can still consider our challenge to 14 years of NSA telephone records collection from millions of innocent Americans,” said EFF Civil Liberties Director David Greene.

But government attorneys say it’s impossible to cull the data to just the 10 ongoing cases. Indeed, the attorneys won’t even acknowledge what records they have or which phone carriers they have targeted — creating a legal morass.

The government is not holding on to only the metadata, but it also still has everything it derived from the data — the information it turned up in the “hops” when it investigated suspects’ phone numbers.

Mr. Barrett, the intelligence office spokesman, said they plan to expunge the query data once they are free to get rid of the metadata itself, with “narrow exceptions” laid out in a November order from the secret court.

The court order suggests those exceptions could be broad. The court said the government can retain “information derived from the metadata that has been previously disseminated,” as well as “select query results generated that formed the basis of such disseminations.”

Patrick C. Toomey, a staff attorney at the American Civil Liberties Union, said limits must be imposed.

“The government should purge the call records it collected illegally, including the results of its queries, and should retain only the data necessary to comply with its legal obligations,” he said.

But he said that’s not enough. “The NSA continues to search and store Americans’ private information in vast quantities under other spying programs, all without ever obtaining a warrant,” he said.

Not all of those challenging the NSA want the data expunged.

Larry Klayman, a conservative lawyer who won his case against the NSA in federal district court in Washington, says the data are needed so he can win a massive settlement from the administration.

“We basically want to show what it is that they have control over, and have had access to, to make our claim to damages,” he said.

Mr. Klayman also doesn’t trust the NSA to expunge the data even if it’s ordered to.

“To me it’s irrelevant, any kind of agreement you reach with them,” he said. “I want them to preserve all of it because I know even if they say they’re purging it, they’re not going to.”

He said the only acceptable solution is to have the federal judge in his case, Judge Richard J. Leon, oversee the NSA’s activities going forward.

• Stephen Dinan can be reached at sdinan@washingtontimes.com.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.