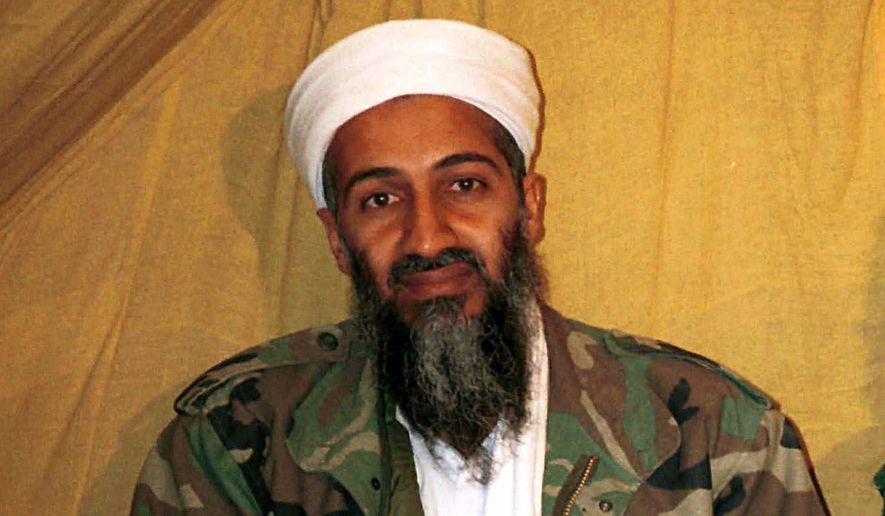

Osama bin Laden grew increasingly paranoid during the years leading up to his capture and death in 2011 — at one point expressing fears that Iranian dentists had planted a tiny tracking device in his wife’s tooth filling.

But the al Qaeda leader was also defiant and apparently believed right up to the end that his terrorist organization was winning in its jihad against the West. “Here we are in the 10th year of the war, and America and its allies are still chasing a mirage, lost at sea without a beach,” he wrote in a letter addressed to “The Islamic Community in General.”

Those are just a couple of the juicy takeaways from the U.S. intelligence community’s latest release of classified documents seized during the May 2011 Special Forces raid that killed bin Laden at his compound in Abbottabad, Pakistan.

The Office of the Director of National Intelligence on Tuesday published a tranche of 113 documents — dating mostly from 2009 to 2011 and translated from Arabic into English — on a website for public consumption.

Although U.S. intelligence has pored over the terrorist leader’s letters for nearly five years, their most haunting passages could yield new insights as Washington struggles to lead the global fight against a terrorist threat that has evolved dramatically and — by some accounts — grown since the horrific attacks of Sept. 11, 2001.

The U.S. and its allies “thought that the war would be easy and that they would accomplish their objectives in a few days or a few weeks,” bin Laden boasted in the general letter, which he is believed to have written sometime in the weeks or months just before his death.

“They did not prepare for it financially, and there is no popular support that would enable it to carry on a war for a decade or more,” he wrote. “The sons of Islam have opposed them and stood between them and their plans and objectives.”

Winning the war on terrorism?

The question in some national security circles Tuesday centered on the extent to which those “sons of Islam” continue to hold an edge — not only in Syria and Iraq, where al Qaeda’s jihadi rival, the Islamic State, has arisen and seized large swaths of territory in recent years, but also in bin Laden’s former stomping grounds of Afghanistan and Pakistan.

The documents were released Tuesday morning as news broke that two Pakistani employees of the U.S. Consulate in Peshawar had been killed in a roadside bomb attack.

The bombing put nerves on edge at the State Department and cast a shadow over a top Pakistani diplomat’s attempt to draw Washington’s attention to his country’s accelerated campaign against jihadis for the past 18 months.

Sartaj Aziz, the top national security and foreign policy adviser to Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif, told reporters on a Washington visit that Pakistan’s military has cut the number of terrorist attacks in the nation by half — from about 300 a year to roughly 150 over the past 12 months.

“If you look at the rest of the world, the incidents of terrorism are growing and Pakistan is under control. So I think we could almost venture to say we are turning the corner, but I’ll wait for a few months before we say that because I think we are still in the process,” Mr. Aziz said.

Secretary of State John F. Kerry condemned the Peshawar attack, which could result in further deepening of U.S.-Pakistani counterterrorism relations, which have been rocky over the past decade but have warmed over the past two years.

Officials on both sides say relations are stronger today than at any other point since the bin Laden raid, which was carried out without Islamabad’s knowledge. As a result, acrimony soared and bilateral dialogue was suddenly halted.

After much hand-wringing on both sides over the extent to which Pakistan may have known the al Qaeda leader was hiding in their midst, the two sides resumed their strategic dialogue in 2013. Mr. Aziz was in Washington this week for the latest round of talks with U.S. officials.

Terrorist’s will

Among the more interesting findings in the bin Laden document dump were those portraying the al Qaeda leader’s growing paranoia and his vision for a seemingly endless terrorist war against the West.

The Associated Press, which received advanced access to the records, noted that in one document — a handwritten will — bin Laden claimed he had about $29 million in personal wealth, the bulk of which he wanted to be used “on jihad, for the sake of Allah.”

The al Qaeda leader planned to divide his fortune among his relatives but wanted most of his estate spent to support the Islamic terrorist network behind 9/11.

Even as bin Laden bragged that the U.S. war against his followers was failing, the documents show how the threat of sudden death was on his mind years before the fatal raid in Pakistan.

“If I am to be killed,” he wrote in a 2008 letter to his father, “pray for me a lot and give continuous charities in my name, as I will be in great need for support to reach the permanent home.”

An opening in Libya

Publication of the documents marked the second declassification of materials from the U.S. raid on the compound in Abbottabad, not far from the most prestigious Pakistani military academy.

An initial batch released in May showed bin Laden had spent the final years of his life pleading with followers to stay focused on carrying out large-scale, 9/11-style operations against Americans and avoid getting sucked into the regional wars and Muslim-on-Muslim violence that have come to define so much of the global jihadi narrative since his death.

The first records also showed a bin Laden discouraging jihadi offshoots from forming an Islamic State and warning that small wars to topple governments in the Middle East would distract from the big-picture goal of striking the U.S.

Reuters, which also got advanced access to Tuesday’s trove, reported that bin Laden and other al Qaeda leaders were increasingly worried about spies in their midst, drone attacks and secret tracking devices reporting their movements as the U.S.-led war against them ground on.

In one document, bin Laden instructs al Qaeda members holding an Afghan hostage to be wary of tracking technology attached to the ransom payment. “It is important to get rid of the suitcase in which the funds are delivered, due to the possibility of it having a tracking chip in it,” he wrote.

In another document, bin Laden, writing under the pseudonym Abu Abdallah, expressed alarm over his wife’s visit to a dentist while in Iran. He worried that a tracking chip could have been implanted with her dental filling.

“The size of the chip is about the length of a grain of wheat and the width of a fine piece of vermicelli,” he wrote. The letter ended with this instruction: “Please destroy this letter after reading it.”

President Obama has repeatedly stressed how drone strikes and other counterterrorism operations have depleted al Qaeda’s original leadership core in Afghanistan and Pakistan. But the organization has proved more resilient from Afghanistan to North Africa, while the rival Islamic State has emerged in Syria and Iraq and continues to expand its network of affiliates.

U.S. officials have cited particular concern about the Islamic State’s growing foothold in Libya over the past year.

Shortly before his death, bin Laden hailed the overthrow and death of Libyan strongman Moammar Gadhafi in a U.S.-backed military operation. In a Feb. 25, 2011, letter addressed “to our people in Libya,” he wrote that al Qaeda had triumphed over Gadhafi.

“Praise God, who made al Qaeda a great vexation upon him, squatting on his chest, enraging and embittering him, and who made al Qaeda a torment and exemplary punishment upon him, this truly vile hallucinating individual who troubles us in front of the world!” he wrote.

• This article is based in part on wire service reports.

• Guy Taylor can be reached at gtaylor@washingtontimes.com.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.