OPINION:

Nearly a year after its passage, the nuclear deal with Iran — formally known as the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action — remains a political football in Washington. In response to pressure from Tehran, the Obama administration continues to seek ever-greater sanctions relief for the Iranian regime. The justification propounded by administration officials, from Secretary of State John Kerry on down, is that Iran has yet to reap real benefits from the deal and, therefore, a further sweetening of the pot is necessary to ensure its continued compliance with the terms of the deal.

In Asia, however, a very different picture is taking shape. Recent weeks have seen Tehran boost bilateral relations with countries such as South Korea and Turkmenistan on everything from trade to security cooperation in a clear indicator that, with the passage of the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action, the Islamic republic is now well and truly out of the sanctions “box.”

Of the nations seeking to re-engage Iran, however, by far the most significant is India. Long stifled by international sanctions, bilateral ties between Tehran and Delhi are now expanding rapidly — and doing so in ways that could reshape the Asian geopolitical order.

The most public sign of the unfolding thaw between the two countries was a high-profile, two-day state visit to Iran undertaken last month by Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi. The trip yielded a dozen new pacts on trade, telecommunications and transportation in what Mr. Modi and his Iranian counterpart, Hassan Rouhani, termed a “new era” in relations between the two countries.

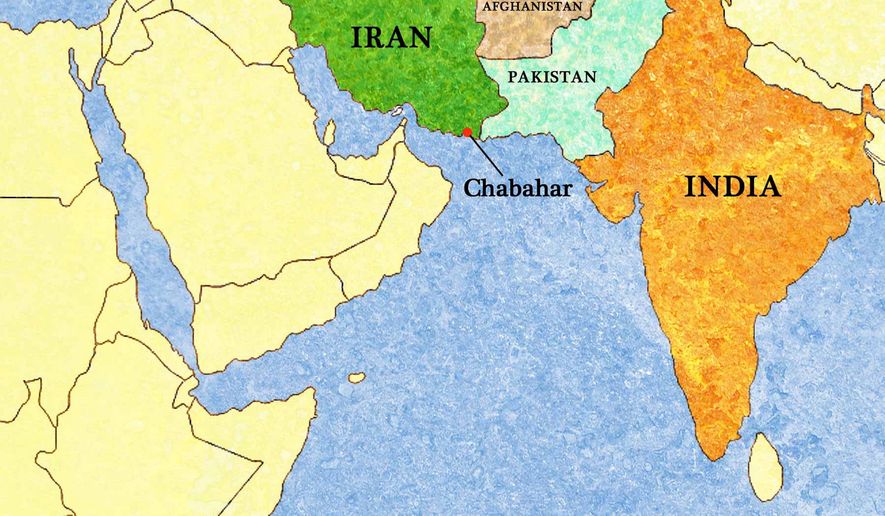

Key among these was the conclusion of a long-discussed agreement for India to build and operate Iran’s port of Chabahar. The multiyear, $500 million deal involves the development of two terminals at the southern Iranian port for Indian cargo destined for Middle Eastern and African markets. It was also a precursor to a trilateral pact that has since been signed between Iran, India and Afghanistan for the creation of a network of rail lines and roads throughout Southwest Asia, which will utilize Chabahar as a transit hub.

For India, the agreement represents something of a strategic coup. The country has long been constrained in its access to Central Asia and Afghanistan by dint both of its geographic location and its fraught relations with regional rival Pakistan, much to the chagrin of officials in New Delhi. Once operational, Chabahar and its associated transportation network will help solve that problem, allowing India to bypass Pakistan and deepen its direct political and economic involvement in both places.

For Iran, however, the deal promises to be even more decisive. In recent years, Iran has consistently sought to deepen its involvement in Asia as a way of counteracting widening Western sanctions, and in order to expand its global presence. This has included, among many other things, plans for the creation of an 800-mile natural gas “peace pipeline” stretching from eastern Iran through Afghanistan and into western Pakistan — a project that was effectively scuppered in 2013 when Iran withdrew half-a-billion dollars in financing for the energy route.

But the Islamic republic still dreams of being a major economic player in Asia, a desire that has been stoked anew by the removal of international sanctions. And the Chabahar port deal could bring it considerably closer to that goal. The agreement positions Iran to become a key transit route for Indian goods, and a significant stakeholder in India’s export strategy. It is also sure to revive Iran’s efforts to erect an alternative energy route stretching into Asia — something that, should it materialize, would create “an unbreakable long term political and economic dependence of billions of Chinese and Indian customers,” according to energy experts.

The Tehran-Delhi detente, meanwhile, continues to inch forward in other ways as well. India’s oil refiners, for example, have taken their cues from the Modi government’s opening to Tehran and are now reportedly preparing to render nearly $7 billion in outstanding debts to Iran — something that will give Iran’s energy-driven economy, now slowly struggling back to its feet, a significant added shot in the arm.

All this makes India’s reengagement potentially significant — and decisive. India’s ties to what is now Iran date back to antiquity, and those civilizational contacts have been buttressed in modern times by a shared distrust of Pakistan and a mutual interest in dislodging the Taliban from Afghanistan. Even so, until quite recently, Delhi was prepared to limit its interactions with Tehran in deference to American and European sanctions.

No longer, it seems. With the implosion of the international consensus over Iran’s economic isolation, India — like many other nations — is beginning to exploit new opportunities in the Islamic republic. In the process, it has provided Iran with an opening to build long sought-after economic bonds to Southwest and South Asia. And it has helped lay the groundwork for a sustained, long-term economic recovery on the part of the Iranian regime.

• Ilan Berman is vice president of the American Foreign Policy Council in Washington, D.C.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.