As the world mourns the passing of Muhammad Ali, the global icon, boxer and father of nine children, I am reminded of my own father’s love for “Cassius Clay,” as he was known at one time.

Some of my fondest childhood memories were of sitting in front of the television as my father watched “The Champ’s” fights. He would be transfixed, glued to the screen, exclaiming and gesticulating passionately at every punch and jab, every flurry, feint and magical display of speed, cunning, power and grace.

Ali’s prowess as a champion — the fact that he is almost universally considered the “greatest of all time” — was incredible, no less because of his performance against formidable opponents in the ring than his willingness to take on the powers that be. During an era in which black professional athletes were clamoring for mainstream acceptance in America, Ali stood out, not only as a graceful champion in a sport that was known for its brutality and shady dealings, but also as a forceful voice for change and progress in America’s battles for racial equality.

While baseball was considered America’s pastime and the National Football League dominated the college sports world — boxing had been, and still is, largely confined to athletes from the wrong side of the tracks who are often led to the sport because their violent behavior outside of the sport needs to be channeled into a more productive pursuit. The business of boxing is the world of the smoke-filled room, the backroom deal, the fix, the planned fall and the dim, bloody, spit-filled gym in the basement of an abandoned building.

Muhammad Ali brought boxing out of the darkness and onto the center stage. He used the platform he gained as a loud-mouthed, self-promoting kid from Kentucky to make a name for himself in the sport. As Cassius Clay, he was known as a brash, boastful upstart, always on the verge of writing a check with his mouth that many doubted he could cash with his fists. His early wins — decisive upsets against mountainous heavyweight champions including Sonny Liston and Floyd Patterson — marked him as a bad boy of the sport, with bloodthirsty sellout crowds assembling in hopes of seeing someone finally shut him up.

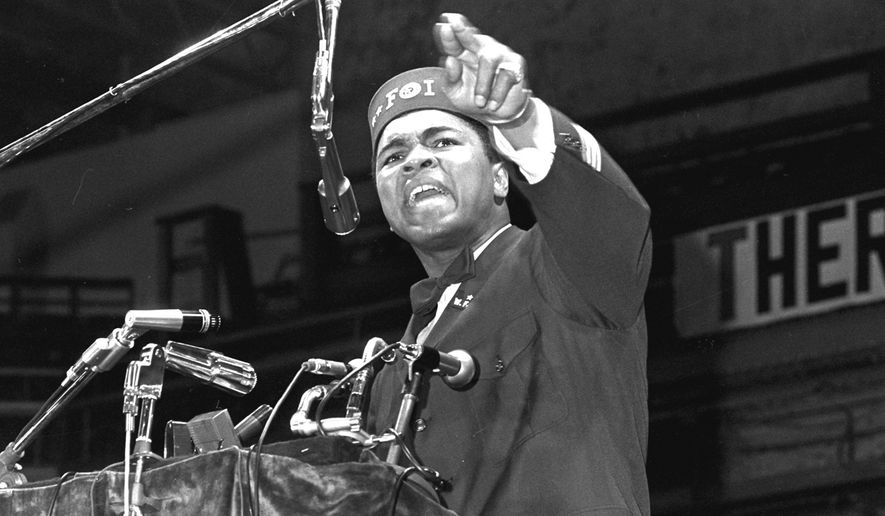

In the final analysis, it would take a far more formidable opponent than another boxer to quiet Ali. He ultimately rejected his “slave name,” as he called it, after an upstart movement called the Nation of Islam and made a religious conversion at the height of his fame and abilities. The man who emerged, Muhammad Ali, was still brash, boastful, clever and confident. He was still a consummate showman. But he did not restrict his battles to the ring. He joined the fray of the civil rights struggle, making racism a central focus of his ire and ridicule. In so doing, Ali went against the grain of American celebrities — particularly black celebrities — who largely stayed out of the political limelight and preferred to help the movement quietly from behind the scenes.

Not Muhammad Ali. He nurtured a public friendship with one of the most controversial civil rights figures at the time, Nation of Islam minister Malcolm X. When Malcolm himself got into trouble with the Nation of Islam for his comments following the assassination of President Kennedy, Ali stood firmly by his friend’s side, a stance that would ultimately take him down the road to perhaps his greatest of all fights: the fight against the U.S. government.

Ali’s decision to refuse to register for the U.S. military draft on the basis of a conscientious objection was undoubtedly one of the most critical turning points in his life. It marked the end of his rise to the top of the boxing world at that moment and the beginning of his transcendence into another realm altogether. Banned from the sport for five years, sued and threatened with imprisonment, Ali stuck to his principles and never wavered in his belief that the Vietnam War represented the hypocritical face of American imperialism abroad in the same way that Jim Crow laws and de jure segregation represented American hypocrisy at home. He raised the obvious question of how it was that blacks could be conscripted to go fight on a foreign land half a world away and yet could not fully enjoy the rights of citizenship here at home. “No Viet Cong ever called me n——r,” he said dismissively.

Ali’s position was, of course, completely at odds with U.S. government policy at the time, and the fact that he was such an influential figure within the black community — within the sports community at large — meant that his act of defiance had to be confronted. He was stripped of his championships belts by the Nevada Boxing Commission and barred from competing in the sport. Ali was not cowed; he dug in with the characteristic stubbornness of a pugilist who had been knocked out but refused to go down. He conceded nothing to his opponent.

But in the intervening five years that Ali was away from the sport, a lot occurred in America that would put his courageous stand in an entirely new light. The first was the realization that America’s global fight against the spread of communism would have to be more about winning the hearts and minds of the rest of the world than about a military battle against communist armies. That realization, prompted by acts of protest by Ali and countless others, by images on television of children being attacked by dogs and fire hoses for daring to assert their equality, finally wore down the intransigent stalwarts of racial segregation and subjugation. Ali himself — having no outside opponent to fight — also faced a struggle within.

Ali’s ultimate return to the ring was symbolic, not just of an evolution in the governing framework of America, but also of Ali himself. While he continued to display a brash demeanor, he seemed kinder, more magnanimous. At the end of his career, beaten and weakened by a few thousand blows too many, Ali retired with a grace that would have been uncharacteristic in the young Cassius Clay. While he was humbled by the early onset of Parkinson’s — a disease that would plague him until his death 30 years later — he accepted it with the resignation of someone who had finally come to trust in the will of a higher power. He realized that all he accomplished, both his challenges and his triumphs, served a greater purpose. And that was what made him truly a transcendent figure, not just in the world of sports, but also as an American ambassador of peace, good will and true greatness.

• Armstrong Williams is a nationally syndicated columnist and sole owner/manager of Howard Stirk Holdings LLC TV.

• Armstrong Williams can be reached at 125939@example.com.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.