OPINION:

As he methodically laid out the case against Hillary Clinton for her use of a private, unsecure server and email accounts to carry out all of her official government business as secretary of state before declining to recommend criminal charges, FBI Director James B. Comey left out one major piece of evidence. It’s the one piece of the puzzle that truly nails her, since it demonstrates consciousness of guilt.

She fired an ambassador serving under her for doing eerily similar, but far less damaging, things.

There has been a lot of chatter about the “lack of criminal intent” since Mr. Comey’s announcement. Consider that “gross negligence” and not “intent” was the standard, and that she asked top staff to remove classified markings from documents sent to her, and that despite her original pronouncement that “there is no classified material,” the FBI found more than 100 classified documents, including several designated Top Secret/SAP. And consider that she instructed her aides to “design the system we want,” one that would prevent “the personal” from being “accessible.”

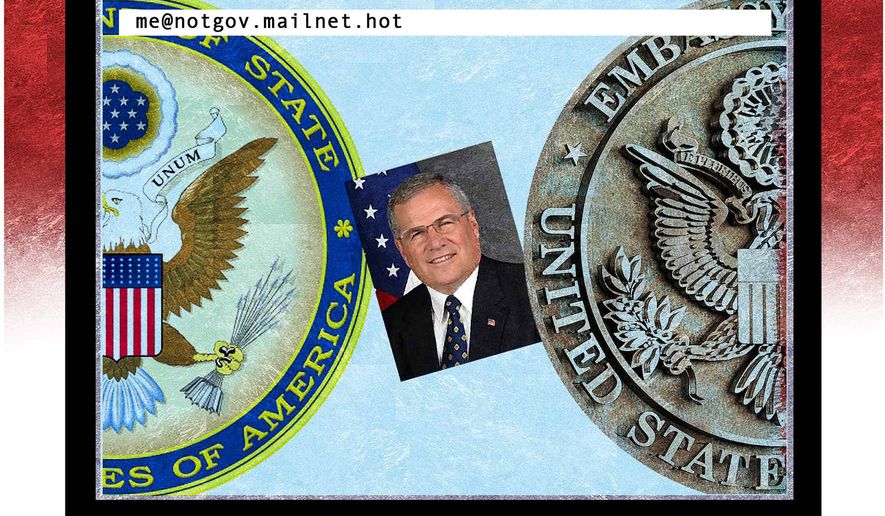

She knew what she was doing. But perhaps the ultimate demonstration of intent was her June 2012 decision to force the resignation of Scott Gration, U.S. Ambassador to Kenya, for, in part, setting up and using an unapproved private email system in 2011.

The matter got scant attention, even after the department’s inspector general’s report was issued shortly after his resignation and after news of Mrs. Clinton’s use of a far more sophisticated private server arrangement broke last year.

“Very soon after the Ambassador’s arrival in May 2011,” the report stated, “he broadcast his lack of confidence in the information management staff. Because the information management office could not change the Department’s policy for handling Sensitive But Unclassified material, he assumed charge of the mission’s information management operations. He ordered a commercial internet connection installed in his embassy office bathroom so he could work there on a laptop not connected to the Department email system. He drafted and distributed a mission policy authorizing himself and other mission personnel to use commercial email for daily communication of official government business. During the inspection, the Ambassador continued to use commercial email for official government business.”

It specifically called him out for willfully violating departmental information security policies, demonstrating his “reluctance to accept clear-cut U.S. Government decisions.”

When Mrs. Clinton’s far more dangerous use of a private, unsecure server came to light, her defenders rushed to fuzz up the issue by pointing to other issues for his dismissal. (At least he just got fired. His fate under this particular boss could have been worse. See: Ambassador Stevens, Christopher.)

But the inspector general’s report made clear that his use of an unauthorized private email system was the primary reason for his firing, stating outright that his unwillingness to obey governmental security policies was his “greatest weakness.”

Following the report’s disclosure, Mr. Gration took criticism from all sides, with leftist publications leading the charge. As the Federalist website detailed last March, The Washington Post recounted Mr. Gration’s various security violations as U.S. ambassador, noting that he had “repeatedly violated diplomatic security protocols at the embassy by using unsecured internet connections.”

A 2012 story in The New Republic noted that Mr. Gration’s email scheme “put classified information about the U.S.’s operations in East Africa at a higher risk for exposure.”

The New York Times wrote that Mr. Gration “preferred to use Gmail for official business and set up private offices in his residence — and an embassy bathroom — to work outside the purview of the embassy staff.”

Mr. Gration’s case takes on urgent importance in light of Mrs. Clinton’s excuses for having done worse: that she made a mistake, that the rules weren’t clear, that the guidelines had changed after she left State, that everyone knew she was using private email accounts.

All lies. And all now excused by the FBI.

Mr. Gration’s case demonstrates that she clearly knew what the rules were — and deliberately chose to violate them.

But Mr. Comey rejected that. She put classified information on a server that she knew was not secure. She caused it to be put there. By way of deferring to her, Mr. Comey chose to invoke the euphemism “extremely careless” rather than legal standard of “gross negligence”.

She obviously knew that her actions jeopardized national security and ongoing operations. And she knew these things because she terminated an ambassador for committing similar but lesser violations. His firing demonstrates more than gross negligence on her part. It shows clear intent and awareness of her own guilt.

Mr. Comey’s decision proves that what was good for the goose is not good for the gander — particularly if the goose’s last name is Clinton.

• Monica Crowley is editor of online opinion at The Washington Times.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.