OPINION:

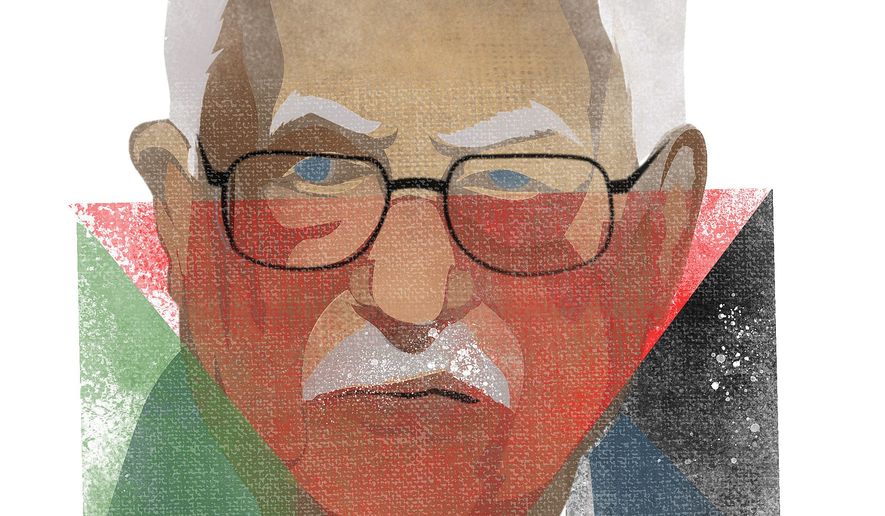

One man, one vote, one time: In 2005, Mahmoud Abbas was elected to a four-year term as president of the Palestinian Authority. He hasn’t bothered to run for re-election since.

He also is president of Fatah, a political movement with past ties to terrorism and the dominant faction within the Palestine Liberation Organization. The PLO was founded in 1964 — three years before Israelis were in Gaza or the West Bank. Mr. Abbas is chairman of the PLO, too.

What all this means is that despite Mr. Abbas’ declining popularity — two-thirds of Palestinians would like him to resign, according to a recent poll — no one has been able to successfully challenge his power on the West Bank.

And last week, at the Seventh Fatah Congress, held at the Muqata’a, his fortified headquarters in Ramallah, Mr. Abbas further solidified his position. With members of rival factions barred from attending, and no other candidates on the ballot, Mr. Abbas was handily re-elected Fatah president. “Everybody voted yes,” Fatah spokesman Mahmoud Abu al-Hija assured reporters who had not been permitted to witness the event.

Mr. Abbas, who also goes by the nom de guerre, Abu Mazen, is 81 years old and not in sparkling good health. He has not named a successor. Nor has he shaped a process likely to lead to a peaceful succession. Dimitri Diliani, a member of Fatah’s Revolutionary Council, told Grant Rumley, a research fellow at the Foundation for Defense of Democracies who covered the meeting: “We used to call Arafat a dictator, but compared with Abu Mazen, Arafat was a champion of democracy.”

What does Mr. Abbas intend to do with the power he possesses in the time he has remaining? I think it’s clear that he doesn’t see himself shaking hands with Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu on the White House lawn. He understands only too well that a “two-state solution” — meaning two states for two peoples peacefully coexisting — would be unacceptable to many within Fatah and the PLO, and to everyone in Hamas, the Islamic State, al Qaeda, Hezbollah and, of course, the Islamic Republic of Iran which, at least for now, is the rising power in the Middle East, a regime whose red lines you don’t cross with impunity.

What Mr. Abbas wants instead is for a Palestinian state to be recognized at the United Nations in the absence of a peace treaty with Israel. Would such a state include Gaza under the rule of Hamas, a jihadi organization openly committed to Israel’s extermination? How would such a state achieve economic viability? Or is the plan to have it remain dependent on the international “donor community” indefinitely? And, most consequentially, who will provide for its national security?

Most of those who call themselves pro-Palestinian focus their attention and anger on the fact that Israelis maintain a presence on the West Bank. They pretend not to comprehend that were the Israelis to bug out tomorrow, it would be only a matter of time before Hamas took over, probably through violence. On more than one occasion, the Shin Bet, Israel’s internal security service, has uncovered Hamas cells plotting Mr. Abbas’ assassination.

In 2005, you’ll recall, Israelis relinquished Gaza. Two years later — two very bloody years later — Hamas established its control. Would putative pro-Palestinians really be content to see Ramallah become like Gaza City? Or worse: Without Israeli security cooperation, who would prevent Ramallah from becoming like Raqqa, Aleppo or Mosul?

The French are said to be working on a U.N. Security Council resolution that, I’ll wager, will ignore such questions and instead demand concrete concessions of the Israelis in return for vague promises by the Palestinians.

In the past, the United States has always blocked such resolutions. But Secretary of State John Kerry, at a Saban Forum on Sunday, implied that might not be the case if the resolution comes up for a vote during the final days of the Obama administration. Why not? Because Israel, he said, is “heading to a place of danger” and needs “a better path to pursue.” And he has “spent a lot time looking at this thing.” (Does he suppose Mr. Netanyahu has not?)

A final word about Mr. Abbas: At the Fatah Congress, he defended his attendance at the funeral of Shimon Peres, the former Israeli president and prime minister, as well as his decision to send firefighters to help Israelis put out blazes, many of them set by anti-Israeli arsonists. “I am not sorry that I went to President Peres’ funeral,” he said. “Representatives of 70 nations participated, and why not us? I’m also not sorry, and don’t need to apologize to anyone, for sending our firefighters to help our neighbors to put out the fire. I feel very strongly as neighbors this is a human obligation.”

But he could not bring himself to acknowledge who those neighbors are: the Jewish nation; people who, as historian Barbara Tuchman once pointed out, are living in the same land, speaking the same language and worshipping the same God as did their ancestors 3,000 years ago.

It may be useful to recall that in June 2002, President George W. Bush offered a “vision” of “two states, living side by side in peace and security.” But to achieve that, he said, would require “a new and different Palestinian leadership,” one willing to “embrace democracy, confront corruption and firmly reject terror.”

Almost 15 years later, such a Palestinian leadership is not in place. That could change. But until it does, there’s no good alternative to the status quo, frustrating as that may be for those who seek peace or at least a process that could lead to that elusive destination.

• Clifford D. May is president of the Foundation for Defense of Democracies and a columnist for The Washington Times.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.