OPINION:

Democratic presidential nominee Hillary Clinton had her first news conference this year on Aug. 5, and the big topic — you guessed it — emails. It’s reminiscent of another candidate for the White House with his letters. That nominee was a Republican, James G. Blaine, the election year was 1884, and the campaign by Democrats concentrated on missives that Blaine sent to railroad officials detailing his congressional favors in return for big bucks. Both Mrs. Clinton and Blaine were veteran politicians: Blaine, representing the state of Maine, served in the House from 1863 to 1876, as speaker from 1869 to 1875 and in the Senate from 1876 to 1881. Also like Mrs. Clinton, Blaine served as secretary of state.

Unlike Mrs. Clinton, Blaine was a captivating orator, dubbed the “Magnetic Man” by congressional colleagues. Like Mrs. Clinton, he was obsequious to his party’s presidents, especially, the scandal-ridden Ulysses S. Grant. And like her, he bought a big house in Washington D.C. during his congressional service, as well as a mansion back in Maine.

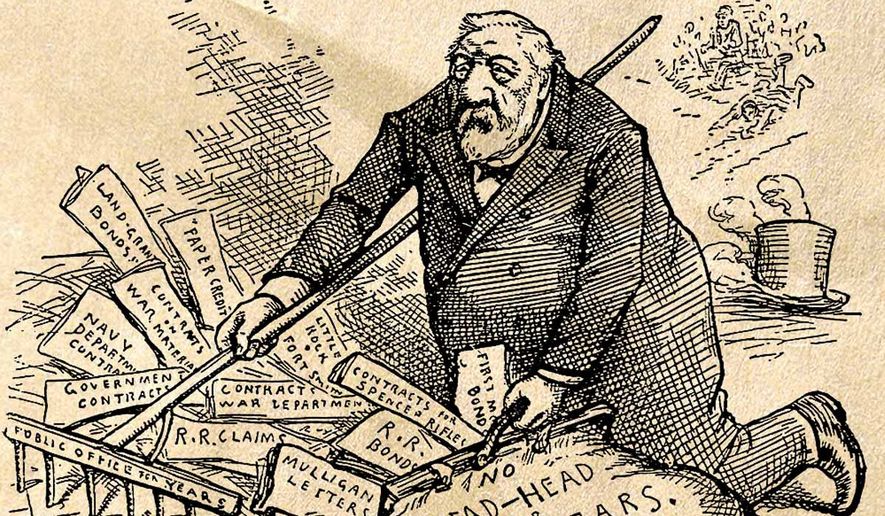

Perhaps the biggest similarity is that Blaine couldn’t shake the controversy over his character. In 1872 he was accused of receiving bribes in the Credit Mobilier scandal in which railroads got favorable congressional treatment. Although no damning evidence was found then, four years later when his name was bandied about as a presidential candidate, clear-cut evidence was found that Blaine received $64,000 that the Union Pacific Railroad paid him for worthless bonds. Blaine’s defense was that he actually had lost money on the deal.

When Blaine finally achieved the GOP presidential nomination in 1884 in his race against Democrat Grover Cleveland, governor of New York, Blaine felt his day had arrived. No Democrat had won the White House after the Civil War, and Blaine was one of the best-known men in the nation. But then some bad baggage appeared, first arising in 1876 when James Mulligan, a Boston clerk who had served as an intermediator between railroad lawyers and Blaine, announced that he had some of Blaine’s letters. But a House investigating committee then went on to clear Blaine of any wrongdoing with respect to the letters. Yet just a few days before Blaine testified before that committee, Blaine had written two letters via Mulligan to one Warren Fisher, a railway attorney.

During the 1884 campaign, Mugwumps — disgruntled Republicans — came up with 20 Mulligan letters, including the two letters to Fisher, which the Boston Herald published on Sept. 15. The first was a false one Blaine had composed for Fisher to send back to him exonerating him from any misdeeds. The second read, in part: “This letter is strictly true, is honorable to you and me, and will stop the mouths of slanderers at once. Regard this letter as strictly confidential … a favor I shall never forget … . Kind regards to Mrs. Fisher. Burn this letter!”

Well, the Democrats had a field day with the revelations, but they had problems of their own. It turned out that Cleveland had sired an illegitimate child when he was sheriff of Buffalo, N.Y. He admitted the transgression, indicating as well that he was providing full financial support for the mother and child.

Disgruntled Republicans had a real problem, but they finally settled on voting for Cleveland in one of the closest elections in history. As for their rationale: “We are told that Mr. Blaine has been delinquent in office but blameless in private life, while Mr. Cleveland has been a model of official integrity, but culpable in his personal relations. We should therefore elect Mr. Cleveland to the public office which he is so qualified to fill, and remand Mr. Blaine to the private station which he is admirably fitted to adorn.”

Perhaps the best similarity between Blaine and Mrs. Clinton, now facing calls from some House Republicans for a perjury investigation, is the Democratic slogan against Blaine: “Blaine, Blaine, James G. Blaine, the continental liar from the state of Maine. Burn this letter!”

• Thomas V. DiBacco is professor emeritus at American University.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.