A Canadian man who was arrested and charged last year for failing to give authorities the password to his cellphone pleaded guilty Monday to violating the federal Customs Act and was ordered to pay a $500 fine.

Alain Philippon of Montreal risked the possibility of prison time and upwards of $25,000 in penalties had he been convicted of “hindering” under section 153.1 of the Customs Act.

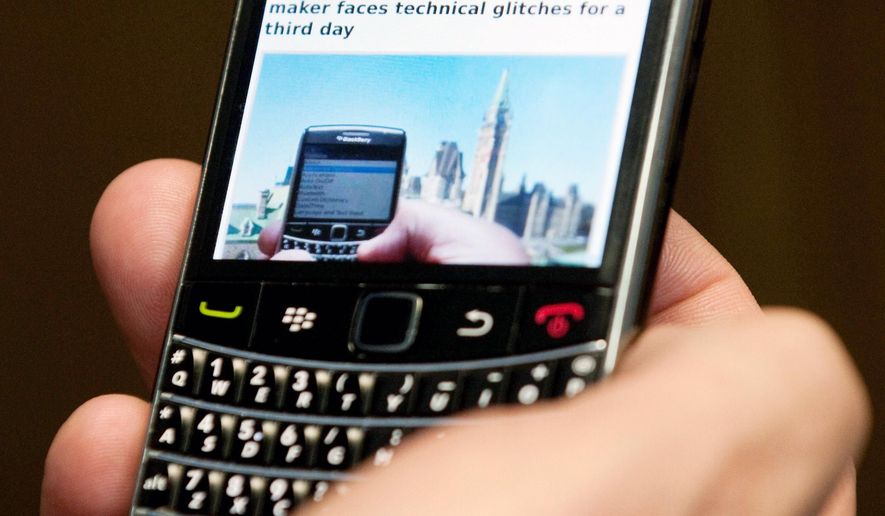

Mr. Philippon, 39, was arrested in March 2015 after returning to Canada from the Dominican Republic. He was approached by officers with the Canada Border Services Agency upon arriving at Halifax Stanfield International Airport and was asked to provide authorities with access to his personal Blackberry. When he refused to give up the password needed to unlock the device, officials charged him with hindering, or preventing an officer from doing his job.

Specifically, the section 153.1 of the Customs Act states: “No person shall, physically or otherwise, do or attempt to do any of the following: (a) interfere with or molest an officer doing anything that the officer is authorized to do under this Act; or (b) hinder or prevent an officer from doing anything that the officer is authorized to do under this Act.”

Mr. Philippon initially pleaded not guilty upon being arraigned last year, but unexpectedly changed his plea during a hearing this week on the eve of a scheduled trial.

A statement of facts read before the court Monday and agreed upon by Mr. Philippson and the government acknowledged that he was carrying two cellphones and $5,000 in cash upon returning to Canada, and that a subsequent swab scan of his luggage tested positive for traces of cocaine.

Mr. Philippon spent a night in custody upon being arrested at the airport, and the seized Blackberry reminds to this day in CBSA’s possession, the National Post reported Monday.

Robert Currie, the director of Dalhousie University’s Law and Technology Institute in Halifax, said Monday’s plea deal represents a “missed opportunity” that could have been used to explore the rarely-discussed legal aspects of Canadian authorities’ ability to compel citizens for access to their personal devices.

“We’ve got case law around the Customs Act, going back in time, which says essentially that you have next to no privacy at the border,” Mr. Currie told the Post. “On the other hand, we’ve got very recent case law from the Supreme Court of Canada, starting in about 2010, that says you’ve got an intense amount of privacy in your electronic devices.

“What we have not seen to date is a case where a court has really wrestled with all of this and tried to put it all together,” he said.

Mr. Currie said previously that the case, had it gone to trial, would have been the first of its kind to be heard in Canadian court.

• Andrew Blake can be reached at ablake@washingtontimes.com.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.