OPINION:

Some years ago, the Conservative Political Action Conference, or CPAC, honored former Sens. James L. Buckley of New York and Eugene McCarthy of Minnesota. Jim Buckley is the late Bill Buckley’s brother and a staunch conservative who in 1970 miraculously won a New York Senate seat on the Conservative Party line and Gene McCarthy was the man who in 1968 forced then-President Lyndon Johnson out of the White House. We were honoring them, however, for the role they played in upholding the First Amendment by successfully challenging the 1974 campaign reforms.

As McCarthy, always pungently honest and outspoken, rose to the applause of a thousand conservatives, he looked out over his audience and said, “You are in real trouble as a movement.” He said that as he walked the halls that day he’d heard people talking about “paleo,” “neo” and a dozen or so other “brands” of conservatism. “I’ve been there,” he warned, “when a movement reaches the hyphenated stage, it is in real trouble. It happened to American liberalism in the ’60s and ’70s and it’s happening to you now.”

McCarthy had a point. The modern conservative movement was bound together from different strains of thought — classical liberal economics, a Burkean concern for order and tradition, a belief in both the wisdom of the American Founders and American Exceptionalism combined with a growing concern about U.S. security in the wake of what most saw as the existential threat posed by an aggressive Soviet Union. The factions quarreled over much, but joined together to form a powerful political movement thanks to the herculean efforts of William F. Buckley Jr. and his colleagues at National Review. Those efforts led to the election of Ronald Reagan in 1980 and domination of one of the nation’s great political parties in the decades since.

Conservatives are by their nature a fractious bunch, but through time they have consistently rallied around certain shared values. At times, national defense questions have dominated the national debate and the debate within the movement while at other times, social or economic issues have seemed to define the movement. In fact, however, while the public focus has changed based on circumstances, the basic views of all these hyphenated conservatives have never varied. The organizers of CPAC have for two decades polled attendees as to their core beliefs and have found a consistent belief in free markets and limited government as the dominant definer of the movement.

It’s time for conservatives who share these values to begin questioning the wisdom of the current fascination with Donald Trump. It is true that the man is successfully channeling the conservative frustration with our elected leaders and the media elite. Applauding his willingness to stand up to the false gods of political correctness is understandable as is the outrage at the way the oh-so-comfortable establishment has reacted to him and his rhetoric, but none of that can possibly justify elevating the man to the presidency of the United States. In fact, based on his public statements he is far more philosophically inconsistent or, dare we say it, “liberal” than any of the “establishment” candidates that so frustrate us.

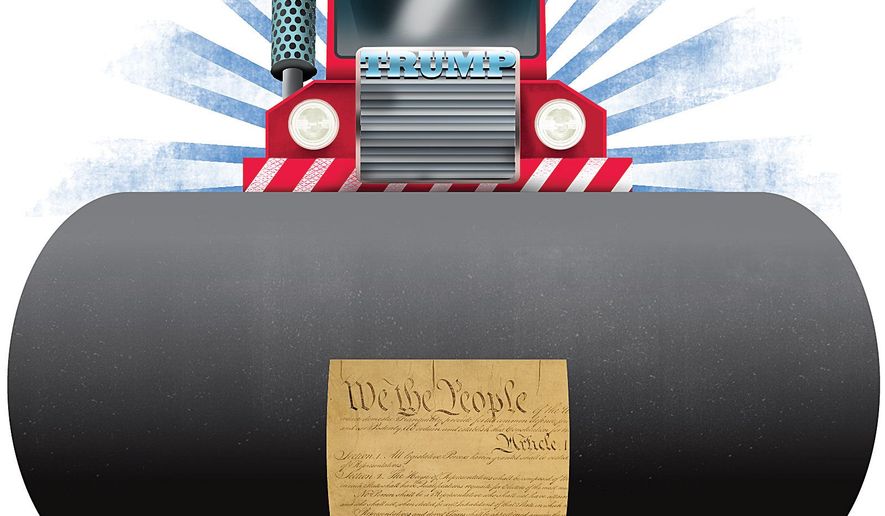

More important perhaps is the matter of temperament. There is always a lot of talk about the “judicial temperament” required of judicial nominees, but the temperament of those we consider elevating to the presidency is even more important. A president’s inclination to abide by the constraints imposed on the office by the Founders is, as we have learned in recent years, directly related to his own concept of his place in the world. The current occupant of the Oval Office finds constitutional limits roadblocks to be bypassed or ignored. Listening to the Donald, one cannot escape the conclusion that he, too, sees himself as too important to be constrained by the scribblings of a bunch of dead white men. That alone is a reason to be skeptical about the man.

One only need go back to his reaction to the Supreme Court decision in the 2005 Kelo case giving government the power to expand the eminent domain power to allow the taking of private property not to build highways, but to give it to others so they can make money and the government can collect more tax money. The decision was radical enough to upset even the militantly progressive Nancy Pelosi, but it didn’t trouble Mr. Trump, one of the few public figures in the country to publicly praise it. “I happen to agree with it 100 percent,” he said while conservatives around the country were tearing their hair out to find ways to restore the balance between individual property rights, government power and the public good.

Mr. Trump’s position then was predictable. He often entered into “partnerships” with local governments and got them to use their power to go after homeowners standing in the way of yet another Trump Tower, park or monument, and he couldn’t understand why private citizens should be able to stand in his way. A man who thought that way then and continues to think that way, regardless of whether he deserves applause for his positions on this or that issue is not one to be trusted with the awesome power of the presidency.

• David A. Keene is Opinion editor at The Washington Times.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.