Like all communist governments obsessed with finding every piece of tangible evidence to prove their all-around greatness, China has yearned to have genuine homegrown Nobel Prize winners to showcase the achievements of the vanguards of the Chinese proletariat.

Yet, several Chinese laureates later, Beijing is finding out that Nobel glory can also be a double-edged sword. In fact, China’s Nobel Dream has frequently become China’s Nobel Nightmare.

That’s because awarding of the prestigious Nobel Prize to Chinese nationals only highlights the country’s profound political backwardness and the regime’s major fault lines, fault lines that could someday undermine the foundations of the Communist Party’s monopoly of power.

Consider the case of the first native-born Nobel laureate for literature, Gao Xingjian, who won the prize in 2000. The government has systematically banned all of his writings and all references to him inside the Web’s “Great Firewall of China,” simply because Mr. Gao openly opposed the 1989 Tiananmen massacre and left China for France to continue his creative writing.

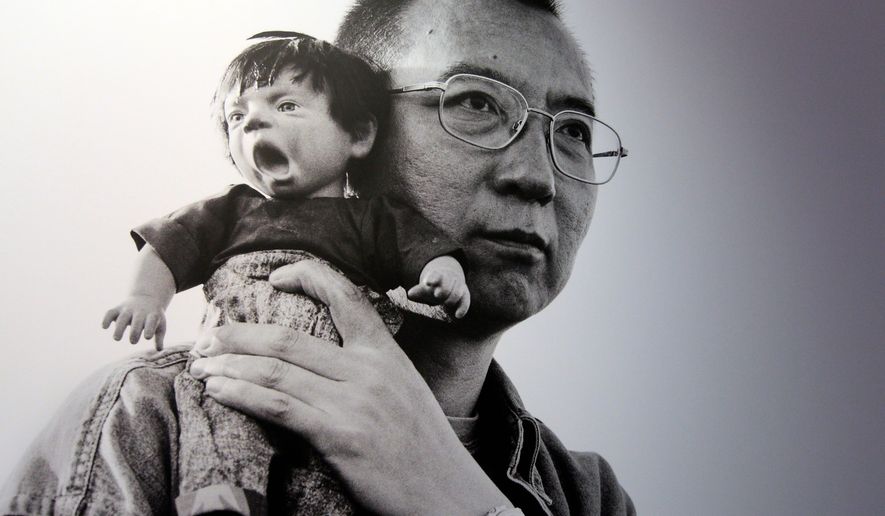

China’s most famous Nobel laureate is 2010 Nobel Peace Prize winner Dr. Liu Xiaobo, a literary critic and human rights activist who, instead of becoming a source of national pride, has become the symbol of China as a pariah state of oppression and dictatorship. Mr. Liu has been in jail since 2009, serving a 11-year term for championing constitutional democracy. By so doing, China is the world’s only country that still jails its own Nobel laureate.

In 2012, novelist Mo Yan, a party member, won the literature prize. But he has since been regarded with great caution by the party bosses, in part because his works are replete with violence, brutality, betrayal and international love twists during the Communist revolution, but mostly because Mr. Mo, whose Chinese name ironically means “do not talk,” was beginning to talk a bit too much, backed by the glow of the Nobel halo.

This week, scientist Tu Youyou shared the Nobel Prize for Medicine with two scientists from Ireland and Japan. Yet Ms. Tu’s honor has also served as an indictment of corruption and political influence within the Chinese scientist community.

Despite the tremendous international recognition for her discovery of the highly effective anti-malaria drug artemisinin, a discovery that has saved millions of lives in Africa and elsewhere, Ms. Tu, now 84, has never been admitted into the Chinese Academy of Sciences. The most prestigious scientific organization in the country, the academy is filled with many phony scientists whose full-time jobs are senior government officials, Communist Party secretaries, wealthy state-owned corporate executives and university presidents who are serial plagiarists, all roaming around the halls of sciences pretending to be thoughtful and accomplished.

The day after Ms. Tu’s Nobel award was announced, a deeply embarrassed government official, speaking to the People’s Daily, the party’s mouthpiece, asked the embarrassing question that was on the mind of the entire nation: “Why has Tu Youyou never been elected to the Chinese Academy of Sciences?” The failure to offer her membership long ago points out the nepotism and flawed election procedures within the academic institution.

Countless readers responded to the article by lambasting corruption in the academy as a microcosm of the corruption of the nation’s political structure as a whole.

It’s a fundamental contradiction: While the government always stresses collectivism, where all major scientific discoveries must be credited to collective efforts led by the all-knowing Communist Party, the Nobel Prize celebrates the triumph of individual achievement.

Ms. Tu embarked on her research following a call from Mao Zedong himself to find the drug for his North Vietnamese comrades in the late 1960s who were dying of malaria. She was part of an enormous secret search project, but in the end, she made the crucial contribution and discovery inspired by ancient Chinese medicinal wisdom, a breakthrough which also won her the 2012 Lasker Award, the medical profession’s top honor after the Nobel. Yet for many in Beijing, giving Ms. Tu the sole honor denies the role of the communist government and the collectivism it prizes.

The specter of collectivism is still haunting China. Hours after the announcement of her award, a reporter from the official Xinhua news agency was knocking on her door, and the first state media report blasted out the headline: “Tu Youyou: My Nobel award is the collective honor of all Chinese scientists.” That was in sharp contrast to 2012, when she rigorously defended her singular contribution to the discovery of artemisinin as the reason she won the Lasker Award.

“Tu Youyou’s award is not only her own glory but also the glory of all Chinese scientists involved in the project,” proclaimed the website of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, the very group that had denied her membership three times in the past. “It is the glory of all of our nation’s medical professionals. It is the glory of the our great motherland, our great people.”

• Miles Yu’s column appears Fridays. He can be reached at mmilesyu@gmail.com and @Yu_miles.

• Miles Yu can be reached at yu123@washingtontimes.com.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.