BUCHAREST, Romania — Romanian leaders believe they have found a solution to the low pay and corruption that are driving doctors out of this impoverished Eastern European country: legalized bribery.

Among a raft of proposals floated by Prime Minister Victor Ponta to improve Romanian health care, legalized bribery would prohibit doctors from making their services contingent on extra money but would let them accept “gifts” after treating patients as long as they declare the income on their tax returns.

“Better than having all the doctors investigated, I prefer to let them know what is sanctioned and what is not,” Mr. Ponta said in a recent interview with Romanian TV.

The proposal is the latest effort to crack down on the corruption that has flourished in Romania since the fall of communism. The new attitude could be characterized as: If you can’t beat corruption, legalize it.

Mr. Ponta himself is in court fighting charges of forgery, money laundering and tax evasion. Bucharest Mayor Sorin Oprescu, himself a surgeon, was suspended in office this month after he was arrested on charges of accepting bribes from city contractors. Former Prime Minister Adrian Nastase ended his prison term last year after serving 500 days for bribery, blackmail and campaign finance convictions.

In February, the respected Romanian news website Gandul found that 52 out of a total of 564 lawmakers — nearly one in 10 — were either convicted of, investigated for or indicted on corruption charges, or were accused of conflicts of interests.

Bribery, often referred to as “the envelope,” is especially widespread in Romanian health care. The typical doctor earns $369 per month, slightly less than the average Romanian’s salary of $398, according to the country’s National Institute of Statistics.

About 28 percent of Romanians said they have given bribes to doctors, compared with an average of 5 percent in the 27 other European Union countries, according to a 2013 Eurobarometer study.

“It would be completely far-fetched to argue that ’the envelope’ didn’t exist in our lives,” said Florin Chirculescu, chief of thoracic surgery at Bucharest’s Emergency University Hospital. “Let’s not be hypocrites.”

Dr. Chirculescu admitted that he took bribes until August, when the Romanian Supreme Court declared that doctors are civil servants and cannot legally accept bribes.

Bribery convictions carry sentences of two to seven years in prison, but few if any doctors are ever brought to trial.

The few prosecutions of physicians illustrate their desperation. Early this year, Romanian anti-corruption investigators indicted Dr. Csiki Csongor, an oncologist in the city of Miercurea Ciuc, on charges of accepting bribes of as little as $13 in exchange for consultation and writing prescriptions.

However, many Romanian doctors are horrified by the prospect of legal bribes.

Elena Copaciu, an anesthesiologist at the Emergency University Hospital, launched a Facebook group as a clearinghouse for opponents of Mr. Ponta’s idea. The group’s 33,000 members believe the government should be reforming medicine, not institutionalizing black-market health care, Dr. Copaciu said.

“Such a proposal is unacceptable and profoundly undemocratic,” she said.

One-third of doctors gone

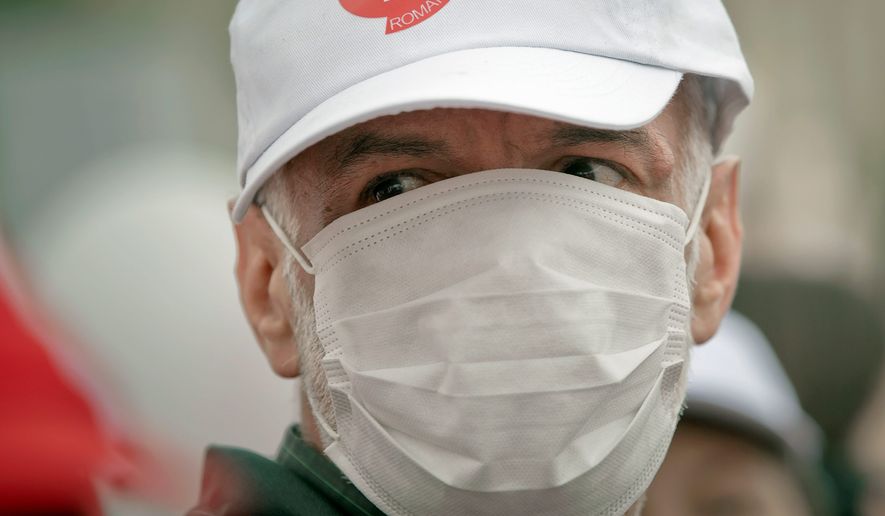

Mr. Ponta also boosted doctors’ salaries by 25 percent Thursday as part of his reforms. Health Minister Nicolae Banicioiu has proposed letting doctors perform work on the side for additional income.

“The doctors and the medical staff can work in the state system after hours, using hospital infrastructure so they will be able to obtain additional, taxed income and so would their teams,” Mr. Banicioiu said in an email to The Washington Times.

Dr. Chirculescu doubts those measures will be enough.

“I don’t know if this more than modest growth that the government offered will fill the absence of the envelope,” he said.

Corruption is a symptom of other problems in Romanian health care, said Nistor Calin, deputy chief prosecutor of the Romanian government’s National Anticorruption Directorate.

“It means overpriced acquisitions, illegal drug reimbursements, unsanitary spaces in hospitals and, not least, a sick population,” he said, noting that the country’s health care budget has increased annually without improved health metrics.

The situation is driving doctors out of Romania in droves. More than 7,000 doctors, a third of the total, left the country in 2011 and 2012, according to the Romanian College of Physicians. EU rules make it easy for them to find jobs in wealthy countries such as Britain, France and Germany, where physicians are required to care for aging populations.

Laura Stefan, an analyst for the think tank Expert Forum, said Mr. Ponta’s proposal reflects how the government has capitulated to corruption rather than pursuing genuine reforms.

Legalized bribery in medicine could spread to the rest of the economy, she said. The exodus of doctors gave Romanian health care professionals leverage in lobbying the government to legalize bribes and increase their income, but other professions could make the same argument, she said.

“Why is it OK for the doctor to accept a bribe and for the professor it’s not?” Ms. Stefan said.

A Romanian doctor who found work in Bielefeld, Germany, after she had completed her residency said she left home this summer for a host of reasons. Her monthly salary, which would have been $330 in Romania, was only one of the reasons, said Dr. Mihaela, who asked to be identified with a pseudonym.

“The operating room was actually a small room with a dirty bed where everyone used to wear the same shoes as outside,” she said. “Lots of dirt. The nurses would steal the cleaners and the food from patients. It was the same in all the hospitals I went to, because we needed to go to different hospitals during residency.”

Germany welcomed her with open arms.

“The deficit of doctors is high here, and they want Romanians because they are hardworking,” she said. “It’s full of Romanians.”

Please read our comment policy before commenting.