Kathryn Steinle’s death in San Francisco in July has done little to break a years-old stalemate over sanctuary cities, which continue to operate under a haze of complex federal rules, competing court decisions and tricky political recriminations — but without very much data on either side of the debate.

Indeed, as the Senate prepares for a make-or-break vote Tuesday, the main attribute of sanctuary cities is just how little is actually known about them, and whether they work to bring down crime rates or, as critics charge, serve as hot-spots for criminal illegal immigrants eager to gain a foothold in the shadows of the U.S.

The two sides can’t even agree on how many there are.

U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, the federal agency that polices immigration in the interior of the country, counts some 340 jurisdictions, according to the Center for Immigration Studies, a think tank which maintains a map with most of those cities and counties listed.

But police and sheriffs in many of those municipalities are stunned to find themselves listed, insisting they do what they can to help federal authorities, while trying to balance that with the need to focus on the crimes that most plague their communities.

“I think we’ve got a lot of passion around the issue. I don’t know we’ve been able to have an in-depth dialogue,” Police Chief Richard S. Biehl of Dayton, Ohio, told The Washington Times in a telephone interview. “No one is willing to wrestle with complexity, and this is a very complex issue. My approach here was try to find a reasonable path through complexity in the absence of any guidance at the national level.”

Varying levels of sanctuary

Taken broadly, sanctuary cities are jurisdictions that have policies or limiting cooperation with federal immigration agents.

At their most extreme, cities and counties order their officers not to communicate with federal officials trying to pick up illegal immigrants for deportation. Other jurisdictions cooperate to some extent, but refuse to honor “detainer” requests that ask for immigrants to be held beyond their usual release date, so federal agents can eventually come get them.

The Homeland Security Department says local authorities ignore about 1,000 detainer requests every month, which means agents then have to go track those immigrants down in the community at large — a much more dangerous, time-consuming and expensive operation, department officials say.

Only about 30 percent of the illegal immigrants released were eventually apprehended, according to the Center for Immigration Studies, citing internal Homeland Security reports, leaving thousands of dangerous wanted criminals out on the streets.

One of those is Juan Francisco Lopez-Sanchez, an illegal immigrant who’d been deported five times and snuck back after each removal. He’d been serving a federal prison sentence but was released to San Francisco County authorities on a years-old warrant, which local prosecutors then decided not to pursue.

Rather than turn him back over to federal authorities, the sheriff released the man, and he now admits to shooting Steinle on July 1 as she walked on Pier 14 — though he says it was an accident.

A national debate ensued, and Republicans in Congress have moved to crack down on sanctuaries.

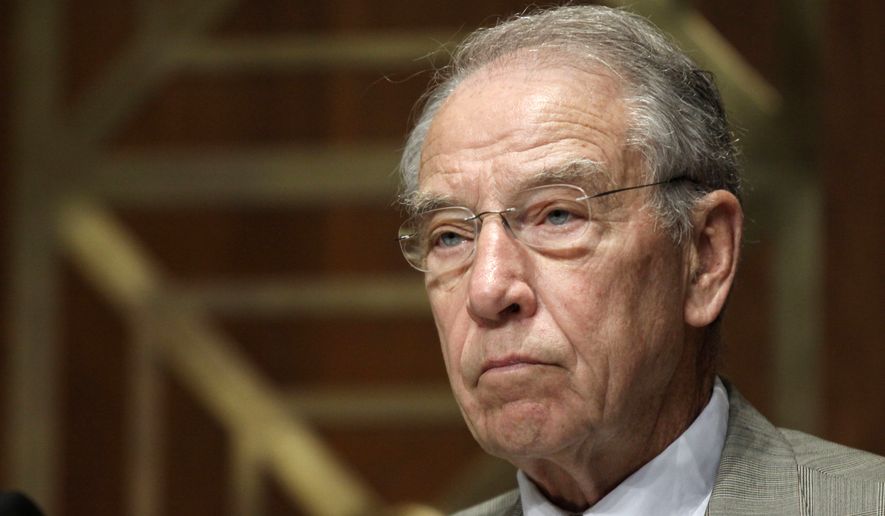

“The suspect in Kate’s death admitted that he was in San Francisco because of its sanctuary policies,” said Senate Judiciary Committee Chairman Charles E. Grassley, Iowa Republican.

He and fellow Republicans are pushing legislation that would affirm local officials can legally cooperate with federal detainer requests. It would also strip sanctuary cities of some federal grant money and dole it out to other jurisdictions that do cooperate.

A first vote on the bill is expected Tuesday, though Democrats are expected to filibuster it.

Democratic resistance

On Monday, Sen. Richard J. Durbin, Illinois Democrat, countered that the problem in the Steinle killing wasn’t San Francisco’s sanctuary policy, but rather bad communication. He said federal prison officials should never have released Lopez-Sanchez to San Francisco on a years-old warrant that was unlikely to be pursued.

He also said the consequences of the GOP bill could be disastrous for Chicago, facing a spike in violence, which gets about $30 million in grants that could be docked because the city is a prominent sanctuary.

Mr. Durbin said local police also fear illegal immigrants won’t report crimes if they believe local police are involved in immigration enforcement.

Studies, however, are hard to find on either side of the issue — which is not surprising given that estimates of the illegal immigrant population itself are hotly debated, and jurisdictions don’t ask the legal status of people who dial 911.

Some research suggests immigrants are already less likely to report crimes for fear of ending up on immigration authorities’ radar, but other research suggests no major changes in service calls when cities have enacted policies either way.

No need for study or time for ’BS’

Austin Police Chief Art Acevedo says there’s no doubt his city’s policies, which have earned it the label of “sanctuary,” have helped with his policing. He bristles at Congress’s efforts to try to force more cooperation, which he says risks turning local police into an arm of federal immigration enforcement.

“I don’t need a study, I don’t need data, I’ve got real life experience after 29 years on this job that tells me this is bad policy,” he said. “I don’t have time for BS, and it really upsets me that I have to spend time combatting bad policy that’s really playing on people’s emotions.”

He said the same folks who complain about politicization of mass shootings are the ones arguing that Steinle’s death should be a call to action on immigration.

Chief Acevedo also vehemently objects to descriptions of his city as a sanctuary, saying he and his officers “fully” cooperate with federal authorities. He also points to record deportations from central Texas and wonders how that squares with Austin and surrounding Travis County being sanctuaries.

But he minces no words in saying he sees no use in wasting resources on cases he says should not be priorities, such as “your cooks, your nannies, your day laborers.”

Conflicting legal guidance

Trapped in the middle of the debate are police chiefs and sheriffs who do see illegal immigrants as a potential safety threat and who are trying to figure out how to policy their communities as best they can with confusing guidance from the federal courts, Homeland Security and Congress.

Sheriff Justin Smith of Larimer County, Colo., says he wants to cooperate, but he and other sheriffs in Colorado have been told by their lawyers that they could face lawsuits if they hold illegal immigrants for pickup by federal authorities, because they would be holding someone without reason — a potential violation of the Fourth Amendment.

For those being released after prison or jail sentences, it’s not so difficult: The release time is usually set, and federal authorities can be notified to be there for a handover.

But for someone being processed after an arrest, release times often depend on how quickly a judge moves, or when someone posts bail — making it much tougher to coordinate a handoff to federal authorities.

“We can’t do anything to slow down that process or we end up in that Fourth Amendment seizure issue,” Sheriff Smith said.

He said he even explored whether he could turn someone over to ICE early, before their sentences were completed at the local level, but his judges told him that wasn’t allowed under their interpretation of Colorado law.

While Republicans in Congress threaten sanctuary cities with the stick approach, Homeland Security Secretary Jeh Johnson — who has been critical of the jurisdictions — has settled on the carrot approach. He’s changed his own policies to try to convince local authorities he’s only targeting the worst of the criminals, not rank-and-file illegal immigrants.

Known as the Priority Enforcement Program or PEP, it has lured some major jurisdictions back to cooperating to some extent.

Chief Biehl in Dayton says he’s more comfortable with the PEP program, which has clear guidelines delineating when ICE requests to be notified of someone’s release, versus a request that someone be detained for pickup.

But Sheriff Smith in Colorado says the program ends up letting the federal government hide the extent of the illegal immigration problem, because all of the information is controlled at the federal level.

“This has made it effective for them to drive down the numbers, which is exactly what it’s intended to do,” he said.

Sheriff Smith said the Obama administration’s moves are driving a wedge between enforcement-minded authorities such as himself, and the voters and activist groups that want to see a crackdown on illegal immigration.

“Instead of us both pointing at PEP and pointing at Jeh Johnson and the president and this very poor plan of enforcement, we’re busy pointing fingers at each other,” he said.

• Stephen Dinan can be reached at sdinan@washingtontimes.com.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.