Australia and Britain have been held out as examples of foreign countries that moved quickly to impose gun restrictions in the wake of national tragedies as the United States grapples with what — if any — policy reforms could prevent future mass shootings like the recent attack in Oregon.

Both countries saw a drop in gun-related crimes after imposing restrictions, though analysts debate whether the laws deserve credit.

But all sides agree the moves Britain and Australia took — far-reaching schemes that many equate to gun confiscation — have zero chance of being accepted in the U.S., where the Constitution offers firm protections for the right to bear arms.

Still, the comparisons are tempting for gun control advocates who envy other countries’ quick response to just a single mass shooting with strict laws.

“Friends of ours, allies of ours — Great Britain, Australia, countries like ours,” President Obama said in the aftermath of the shooting at Umpqua Community College. “So we know there are ways to prevent it.”

Australia was spurred to action after a 1996 shooting in Port Arthur, where a gunman killed 35 people and wounded about two dozen others, prompting a government gun buyback and other measures tightening the requirements for gun ownership.

SEE ALSO: Democrats divide deeply over guns in debate

British authorities, meanwhile, moved to ban certain types of guns after shootings in 1987 and 1996. And both countries now require would-be owners to demonstrate a need, beyond mere self-defense, to justify having a firearm.

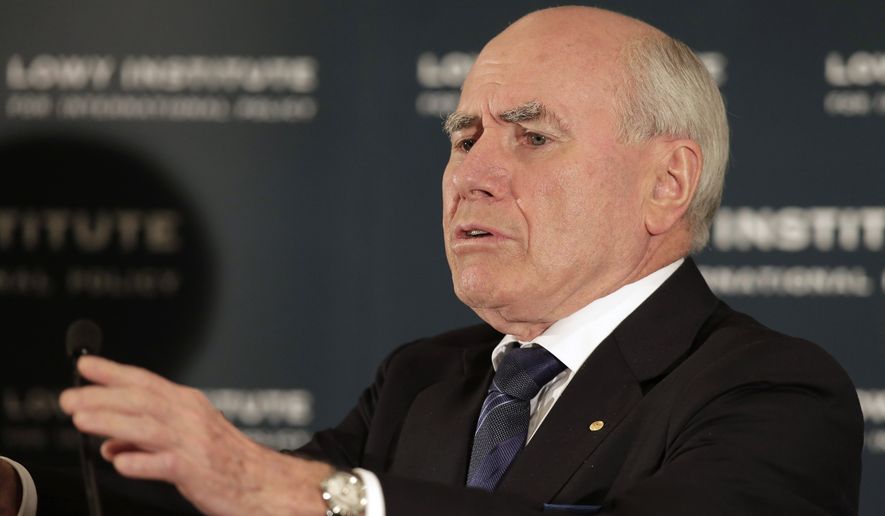

Former Australian Prime Minister John Howard, who helped shepherd the laws with broad public support amid conservative opposition, actually held out the U.S. as an example of what not to do on gun laws, and said at a forum last month the figures are “undeniable” that gun-related deaths have fallen and that a referendum would have carried “overwhelmingly” had the question been put to the states.

Indeed, the number of gun deaths in Australia fell from 674 in 1988 to 226 in 2012, according to the website GunPolicy.org, hosted by the Sydney School of Public Health at the University of Sydney.

“There’s no doubt that a key element remains the almost universal Australian public and political determination not to ’go the American way’ regarding guns,” public health professor Philip Alpers, the site’s editor and founding director, said via email.

Mr. Alpers estimates that more than 1 million guns have been captured and destroyed through the buyback program, with public enthusiasm so strong that in many of the cases, the owners didn’t even get paid for relinquishing their firearms.

The professor said other influential changes after Port Arthur included a ban on all private sales and transfers, universal firearm registration, police-inspected home security for both guns and ammunition storage, background checks requiring proof of a “genuine reason” for gun ownership and mandated police removal of firearms in “stressed” situations, notably domestic violence.

But John R. Lott Jr., president of the Crime Prevention Research Center, said gun-related homicides and suicides were declining in Australia even before the restrictions were imposed, and the trend simply continued after the new laws.

“It’s really hard to look at Australia and find anything that goes and supports the clamor of gun control advocates,” he said.

Mr. Lott said that while many guns were relinquished, ownership rates are now back to about the same as before the new restrictions, suggesting that the number of firearms doesn’t determine the rate of gun crimes.

Difficult comparisons

For Australians, however, the conclusions remain solid.

“The vast bulk of Australians have the same view on this issue,” Mr. Howard said at last month’s forum, hosted by Gun Control Australia, according to The Sydney Morning Herald. “My sense is that this is something the Australian public thinks we got right.”

U.S. advocates also point to the United Kingdom, where gun controls were imposed in waves: The Firearms Act banned certain kinds of rifles in 1988 after a gunman killed 16 people in Hungerford a year earlier; then a 1996 shooting at a school in Dunblane, Scotland, spurred tighter restrictions on gun ownership and a buyback program akin to Australia’s.

Since then there has been just one prominent mass shooting in the U.K., when a gunman killed 12 people in Cumbria in 2010.

Mr. Lott, though, said the homicide rate in the U.K. was already low compared to the U.S., and a more than 14 percent increase in police officers on the streets could account for the further drop in gun crimes.

“That’s a pretty hefty increase,” he said. “I think police matter — I think they matter a lot.”

The desire among gun control advocates to respond was evident at Tuesday’s Democratic presidential candidates debate, though two of the five candidates onstage — Sen. Bernard Sanders of Vermont and former Sen. Jim Webb of Virginia — said voters, often from rural areas, who believe in the fundamental right to own a gun must be respected.

“As [a] senator from a rural state, what I can tell Secretary Clinton [is] that all the shouting in the world is not going to do what I would hope all of us want,” Mr. Sanders said in response to criticism on the issue from front-runner Hillary Rodham Clinton.

Mr. Sanders said he supports measures like expanding gun purchase background checks and touted his D- rating from the National Rifle Association, illustrating that Democrats aren’t even unified on the hot-button issue in the face of near-unanimity among Republicans and groups like the NRA.

In a 2013 survey of other countries’ gun laws, the Library of Congress found that illegal handguns were still “easily purchased” despite stricter laws; in the two years following the U.K.’s 1997 handgun ban, the number of crimes in which a handgun was involved actually increased 40 percent.

More broadly, however, the Library of Congress found that low gun ownership did correlate with low gun crimes.

China, where civilian ownership is generally prohibited, reported just 500 gun crimes in 2011 — in a country with a population of more than 1.3 billion people. Japan, which had 271,100 licensed guns in 2011, reported only eight gun violence victims that year.

Whether those countries are valid models for the U.S. is hotly debated.

The 2013 Library of Congress survey, which looked at nearly 20 other countries, concluded that only the U.S. and Mexico enshrined the right to own firearms in their constitutions. Many of the countries had national firearm registries.

Mr. Alper, the Australian professor, said imagining the U.S. could cut gun ownership by a third — as Australia did with its buyback program — is inconceivable.

“I can’t imagine that the U.S. could at any time in the imaginable future duplicate Australia’s destruction of one-third of its national gun stock,” he said. “That would require the smelting of more than 90 million firearms. We and other nations (U.K., Argentina, Brazil, South Africa, etc.) took action before it became too late.”

Israel, which has stringent gun controls for civilians despite its compulsory military service laws, actually decided to loosen restrictions this week in the wake of recent violence.

Public Security Minister Gilad Erdan said Wednesday that those trained to use weapons have stepped up as a line of defense, and he wants to encourage that.

“Many civilians in recent weeks have helped Israeli police neutralize terrorists who carried out attacks,” Mr. Erdan said, according to The Jerusalem Post.

• David Sherfinski can be reached at dsherfinski@washingtontimes.com.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.