Alaska officials have put the final kibosh on the infamous “bridge to nowhere” — a $400 million project tucked into the federal transportation plan 10 years ago that became the symbol of Washington pork, spawned massive voter outrage and forever changed the way the government does business.

State officials concluded late last month that the project was too expensive and too extravagant for now, bringing to an end a 40-year push by locals in Alaska’s far southwestern corner to construct a permanent link between the city of Ketchikan and the airport that serves it.

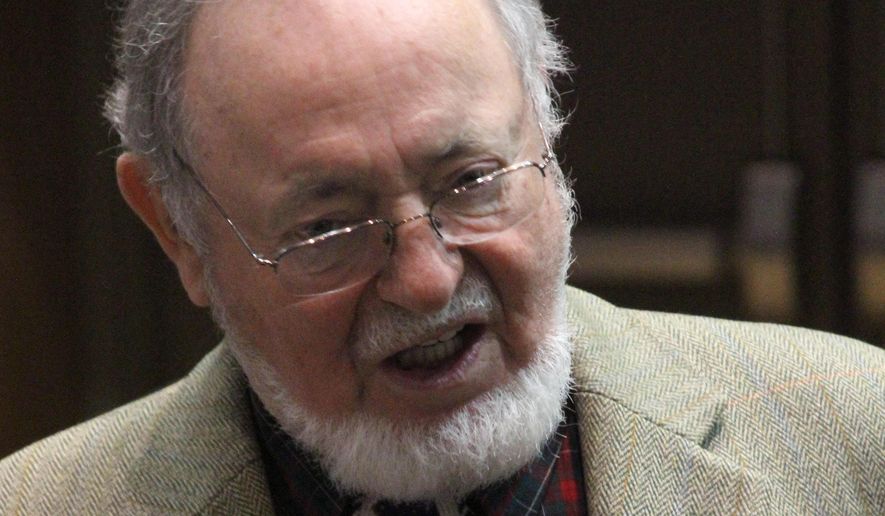

“The thing that just ended it was the economy,” Ketchikan Mayor Lew Williams said after the state officially decided against the bridge, concluding that it made more sense to improve the ferry system that carries passengers from the mainland to an airport across a 1,000-foot strait of water.

The bridge was an “earmark,” or one of those projects lawmakers slipped into bills to direct money to politically important causes back home. But in the hands of opponents, the bridge became The Earmark — the worst of Washington waste.

“That was a big one. It just really hit the public consciousness. People could understand it — the bridge to nowhere,” said Sen. Jeff Flake, an Arizona Republican and prominent anti-earmark crusader who served in the House during the bridge fight.

Known locally as the Gravina Island access project, it was meant to be a permanent connection between Ketchikan, with a population of 8,000, and Gravina Island, with a population of 50, but also home to the region’s international airport.

Alaska’s powerful congressional delegation, including the top House Republican on the Transportation Committee and the top Senate Republican on the Appropriations Committee, managed to secure more than $300 million in federal money through earmarks, which were the equivalents of line-item orders telling federal bureaucrats where to send the money.

For earmark opponents, who had been fighting a losing battle for years, the bridge was a gift — a project that amounted to nearly $8 million for every resident of Gravina Island. Keith Ashdown, then an investigator at Taxpayers for Common Sense, dubbed it the “Bridge to Nowhere,” and a crusade was started.

82-15 vote

The bridge proved to be strangely resilient, beginning with a 2005 bill sponsored by Sen. Tom Coburn to try to cut it. The Oklahoma Republican proposed taking the money and shifting it to Louisiana. Hurricane Katrina had just plowed through the region, ripping apart roads and bridges.

He lost, and it wasn’t even close. The Senate backed the bridge on an 82-15 vote, with senators not so much defending the bridge as much as they were making a statement about their right to earmarks themselves.

The public, however, saw it differently. Fed up with ballooning federal spending under President George W. Bush, Republican voters began to complain.

Some members of Congress who had eschewed earmarks — including Mr. Coburn, Sen. John McCain, Arizona Republican, and Mr. Flake — began to force more embarrassing votes.

After one high-profile Republican, Rep. Duke Cunningham, pleaded guilty in 2006 to bribery for using earmarks to enrich a supporter, Democratic leaders vowed make reforms, including bringing more transparency to the process when they took control of Congress in 2007.

Sen. Barack Obama, who gave up earmarks amid the backlash, took the presidential office in 2009 on a promise of even more scrutiny from his administration, and the numbers and dollar amounts of earmarks dipped as Democrats consolidated power.

Along the way, Mr. Flake and others stepped up their assaults, offering amendments to try to strip earmarks from bills. Mr. Flake said he went to the floor hundreds of times and remembers just one victory: when the House voted against a Christmas tree project in North Carolina. The only reason that one succeeded was because Democrats eager to punish the project’s sponsor joined anti-earmark Republicans.

Still, the public attention was having an effect. Some lawmakers began withdrawing their own earmarks for fear of being embarrassed.

The final demise of the earmark was secured when voters elected a Republican majority to the House in 2010, putting Rep. John A. Boehner of Ohio, a lifelong earmark opponent, in the speakership. Mr. Boehner pushed Republicans to impose a ban on all earmarks, forcing Democrats, who still controlled the Senate, to accept the prohibition. The ban remains to this day.

Mr. Coburn, who retired from the Senate at the end of last year, said it was voters who dragged Congress into the post-pork era.

“The big spenders may have won the Senate vote, but the taxpayer backlash that followed ensured the bridge would ultimately go nowhere and put an end to congressional earmarking altogether,” he said. “What I learned from this and my other experiences in Congress is Washington will never change itself, but with persistence, oversight has the power to stop stupid spending in its tracks.”

’We’ve neutered ourselves’

Rep. Don Young, the Alaska Republican who championed the bridge and remains one of Congress’ biggest champions of earmarks, argues that his colleagues have forfeited part of their power of the purse, which the Constitution delegated to the legislative branch.

“I’m frustrated in the sense that as a legislative body — sent to Washington, D.C., to represent the people — we’ve neutered ourselves,” Mr. Young said in a statement to The Washington Times. “We took away our ability to be part of the system defined by the Constitution.”

He said giving up earmarks isn’t “good government; it is bad government,” because Congress spends just as much but no longer decides what projects receive the money. Instead, members of Congress turn over that power to bureaucrats in the executive branch.

“Unfortunately, we let a bunch of bobbleheads in the media change the conduct of this Congress and make us less free under the control of nameless bureaucrats,” he said.

Those in Alaska found the Washington fight mystifying.

“An earmark is only the money spent in another guy’s district. That’s just political. That’s something back East,” said Mr. Williams, Ketchikan’s mayor.

Officials point out that Alaska has been a state for about 50 years and is still building infrastructure across a giant land mass, which is why so much federal transportation money seems to end up there. Most big state transportation projects are built with 90 percent federal money, with just 10 percent coming from local taxpayers.

Bridge opponents said that kind of arrangement lends itself to extravagant projects because the state doesn’t have bear much of the burden.

Another oddity of earmarks is that Alaska has kept all of the more than $300 million secured by Mr. Young and Sen. Ted Stevens, an Alaska Republican who died in 2010. Most of the money earmarked for the bridge has been spent on other state projects, but some $87.8 million remains in a fund.

Ketchikan officials are intent on making sure that money is used to boost ferry service and make improvements at the ferry terminals. They still think Washington politicians bungled the decision-making. The bridge, they insist, was the right call.

“They’ll learn as soon as they get here and try to get across [the narrows] that bridge access is a very reasonable thing,” Mr. Williams said.

Future of earmarks

Many lawmakers in Washington, including Mr. Young, want earmarks to make a comeback.

Mr. Boehner, before his retirement last month, told reporters he had been approached by another House leader who was wondering whether it was time to revive the practice.

But with 180 members of the House having never served in a Congress with earmarks, it might be difficult to reimpose them the same way.

Thomas A. Schatz, president of Citizens Against Government Waste, which pioneered anti-earmarking and published the annual “Pig Book” to highlight bad spending, said the practice hasn’t disappeared entirely and that some of it has been pushed beneath the surface.

One practice that popped up during the 2009 stimulus program, which was supposed to be free of earmarks, involved key lawmakers sending letters to agencies outlining how they wanted to see money spent. The implication was that agencies’ future budgets would depend on whether they followed orders. Opponents called it “letter marking.”

Mr. Schatz said the amount is much smaller than at the heyday of earmarking but that there is still room for improvement.

New House Speaker Paul Ryan, Wisconsin Republican, has promised to rethink the chamber’s rules. One option could be to ask lawmakers to make their communications to agencies public.

• Stephen Dinan can be reached at sdinan@washingtontimes.com.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.