Landis Bradfield has a master’s degree in nursing and more than 12 years of experience working for the Department of Veterans Affairs, yet he has not helped a patient in nearly six months.

When Mr. Bradfield reports to work at the VA Illiana Healthcare System in Danville, Illinois, he heads to the library at 7:30 a.m. and spends the entire day sitting and doing nothing — just as he has done every day since November. The forced inactivity, he believes, is retaliation for blowing the whistle on poor patient care and other problems at the facility.

Mr. Bradfield raised issues with management about practices such as improperly stored medicine and used syringes, poor performance by other employees and other instances of bullying in the workplace prior to being removed from patient care and forced to sit idle in the library.

Mr. Bradfield is one of two nurses whom the VA is preventing from seeing patients, doing administrative work or taking classes required to stay current on their nursing credentials. Even if the agency said they could go back to work tomorrow, Mr. Bradfield said, he would have to complete almost an entire new employee-orientation process before he was able to get back to his regular job, as all of his training certifications are out-of-date.

“There’s still two of us [who] for six months now have provided no service to the veterans [yet are] drawing full salary. At the very least, that is a waste,” he told The Washington Times. “As an employee, I am glad I’m getting my salary. As a taxpayer, I am very irritated that people get paid to do nothing.”

The VA has long been criticized for retaliating against those who bring to light practices it would rather not address publicly. Last month, a House oversight subcommittee on oversight and investigations hearing aired charges of continued whistleblower retaliation within the VA.

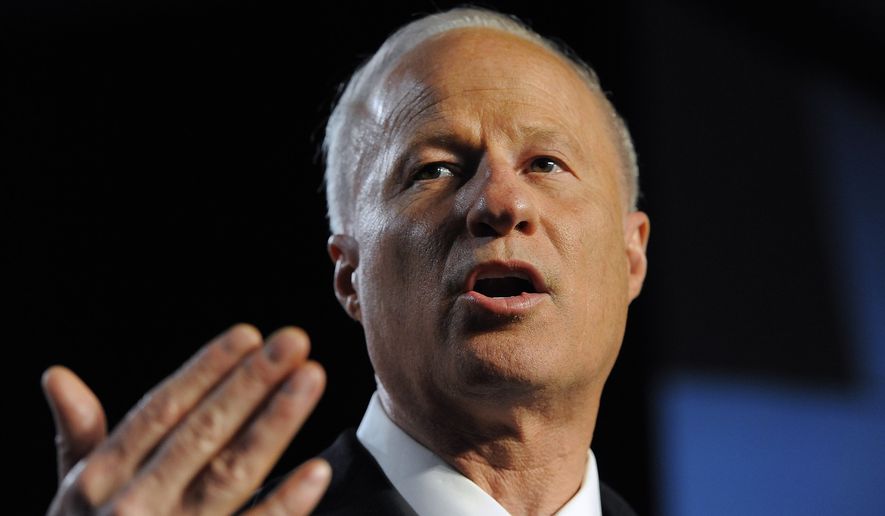

“The retaliatory culture, where whistleblowers are castigated for bringing problems to light, is still very much alive and well in the Department of Veterans Affairs,” subcommittee Chairman Mike Coffman, Colorado Republican, said at the April 13 hearing.

Problems persist

Critics say the retaliation has persisted despite the naming of new VA Secretary Bob McDonald last July. The former top executive at Procter & Gamble was brought in after former Secretary Eric K. Shinseki resigned amid a slew of reports that VA facilities were covering up long patient wait times and poor service. Mr. McDonald, a West Point graduate, has repeatedly promised he would punish officials who retaliated against employees who report wrongdoing.

Yet the problem isn’t subsiding.

“The number of new whistleblower cases from VA employees remains overwhelming,” Carolyn Lerner, head of the U.S. Office of Special Counsel, which oversees compliance with federal whistleblower statutes, told the House Veterans’ Affairs subcommittee hearing in April.

She said over 40 percent of the whistleblower retaliation cases her office is investigating come from VA agencies, more than any other government department. Her office has settled 45 claims since the start of the fiscal year and has about 125 more cases pending.

Ann Good, who works as a nurse for the VA in Danville, Virginia, has also felt the wrath of the VA after she voiced complaints to management.

Ms. Good, who has worked for the VA for eight years, became so bored during the first month she was placed in the library that she sought out administrative work and asked departments if she could make photocopies or do filing.

“I was told I couldn’t do that anymore because it was preferential treatment and [was] told to go sit in the library,” she said. “I just think we’ve ticked some people off, and they don’t want to let us to go back to work, to be honest.”

Wade Habshey, a spokesman for the VA in Danville, said top officials of the facility are aware of the two employees’ complaints about their treatment.

“We have received complaints, and leadership and human resources [are] looking into allegations which have to do with why they were moved from their place of work and transferred to the library,” he said.

Mr. Habshey also said the VA regional office provided information on how to submit a formal complaint to the Office of Special Counsel.

Signs of neglect

Mr. Bradfield worked as a nurse in the Green House Project, a type of long-term care that gives patients more independence and freedom. Patients who cannot live alone are put into homes where they have private rooms as well as shared living rooms and dining rooms, an effort to make the accommodations less like the stark nursing homes typical of long-term care.

Since Mr. Bradfield has been relegated to the library and forbidden to interact with patients, he said three patients in the Green House facilities have developed bed sores — a sign that the department is understaffed as two of its most educated nurses sit and do nothing all day.

He also said those nurses who are still allowed to work in the Green House Project don’t have the time or patience to give residents the freedom the program is designed to provide. For example, Mr. Bradfield said two patients who can only walk with difficulty are no longer walking at all because staff aren’t willing to help prevent them from falling.

“Neither one of those guys can walk now. They just put them in a wheelchair and push them where they want to take them, because they don’t have the time or the patience to deal with them,” he said.

Ms. Good agreed that some patients are receiving substandard care at the facility but declined to go into details, citing privacy concerns of patients. Other nurses in the program who faced retaliation for speaking out have left the VA to go work at other hospitals, she said.

“They kept advising me that I should leave,” she said. “I’m sorry, but the reason I took this job was to make sure veterans are being taken care of. The main part of our job is to focus on the guys.”

Mr. Bradfield said the VA refused to negotiate with him and his lawyer, citing an ongoing investigation, though they wouldn’t tell him what the probe was about. Yet when Mr. Bradfield called the inspector general, he was told there was no ongoing investigation.

As a result, Mr. Bradfield said he decided to file a formal complaint with the Office of Special Counsel.

Neither the VA inspector general nor the Office of Special Counsel returned a request for comment on the case.

Ms. Good said she too has contacted her representatives in Congress and high-level employees at the VA, but has not gotten a response, though she said she will keep trying for the sake of veterans who aren’t getting adequate care.

“If you’re going to just be mean to me, that’s one thing,” she said, adding, “but we know from some things going on out there that [veterans] are not receiving the best care they can get.”

• Jacqueline Klimas can be reached at jklimas@washingtontimes.com.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.