Soccer’s World Cup is big business for host countries, and the game’s organizational structure does little to prevent graft, mismanagement and cost overruns, according to experts who say that driving factors such as tourism, global exposure and long-term infrastructure are chief motivators for some countries to fight — not always fairly — for the right to host.

The stunning indictment by U.S. and Swiss officials Wednesday of top board members of FIFA, soccer’s Zurich-based governing body, has focused new light on the corruption and financial skulduggery that regularly occur at big-time sporting events, especially heavily sponsored, globe-spanning gatherings like soccer’s World Cup or the Olympic Games.

Countries looking to break into the big time are willing to overpay for the “privilege” of hosting an Olympics or World Cup. The small group of largely unelected sports bureaucrats who decide which bid wins quickly realize their votes are valuable.

“I think there’s some true economic motivation, especially when you’re a country like the U.S. and England, the other two main bidders besides Russia and Qatar” for upcoming World Cups, said Victor Matheson, an economist at College of the Holy Cross. “In those cases, this would have just been a cash cow for these places. The U.S. and England were perfectly set up to host the World Cup at almost no additional cost.”

However, the motivations for other countries are not the same, said Mr. Matheson.

“When you’re a Brazil or a Qatar or a Russia, this is much less about the actual event itself than using the event to either advertise yourself or to use the event as an excuse to build all sorts of general infrastructure for the country. The actual World Cup is more of a three-week event, but it’s more like a ten-year building process where you use the World Cup as an excuse to build billions of dollars in general infrastructure.”

Money scandals are nothing new to international sporting events. Mitt Romney famously was called in to rescue the troubled Salt Lake City Winter Olympics in 2002 after revelations surfaced of extensive bribes by members of the organizing committee to win the rights to the games. Even in ancient Greece, judges at the original Olympic Games were often accused of taking bribes and entering their own horses in equestrian events.

Sports economist and author Andrew Zimbalist, who teaches at Smith College, said the problem runs deeper. It’s a system, he told NPR in a recent interview, virtually guaranteed to encourage graft and bribery.

“You have one seller in the case of the Olympics: the [International Olympic Committee]. You have one seller in the case of World Cup: FIFA,” he noted. “And you have cities, or countries, from around the world that are bidding against each other, so you have multiple buyers and one seller.”

The result: “It’s a monopoly situation, and the monopolist takes advantage of that.”

Upfront costs vs. long-term payoff

Mr. Matheson explained that when the U.S. hosted the event in 1994, it brought around 2.5 million spectators, most of whom were visitors from outside the country. When South Africa staged the 2010 World Cup, the first African nation to host the tournament, at least 200,000 more tourists than usual came to the country during the course of the tournament.

But despite the benefits of long-term infrastructure improvements, the upfront cost in hosting a global event like the World Cup or the Olympics vastly outweighs the potential payoff.

“From a pure dollars-and-cents standpoint, it makes absolutely zero sense for a country like Qatar, or even a country like Russia, to host the World Cup,” said Mr. Matheson. “They’re spending billions of dollars on stadiums when they have no soccer league. It’s difficult to see how they’re possibly going to make any money back on this.”

This would not be the first major sport-related boondoggle for Moscow. The 2014 Winter Olympics in Sochi, whose full cost is incalculable but was widely reported to cost the state around $50 billion, drew criticism on several fronts for its cost and location in a subtropical region close to previously embattled regions of Chechnya and Ossetia.

“Sochi was a huge financial debacle and really more of an ego show for Putin than it was any sort of rational financial decision,” explained Mr. Matheson. “They were hoping to make this great resort that would be a long-term tourist draw. Unfortunately, they invaded their neighbor like a week later, so that’s not good for your tourism or your branding. And it’s essentially sort of impossible to have made that much money back from tourism even over a 30-year period.”

Russia has also recently announced that the cost of hosting the 2018 tournament would cost around three times more than the initial $10 billion estimate, with cost overruns another defining feature of major international sports gatherings.

Mr. Putin believes that the benefits of the games will justify the costs in the long run, saying at a recent press conference that while the World Cup is expensive, “if we want to live longer, if we want our people to be healthy and go to skating rinks instead of liquor shops, then skating rinks must be available.”

FIFA’s organizational chart and voting structure also contribute to an atmosphere where corruption and influence-peddling naturally occur.

“One of the issues is that, with FIFA in particular, you have 205 member nations, and each of those member nations has a vote,” said Mr. Matheson, “which means that Togo has the same amount of a vote as Germany and Vanuatu has the same as the United States.”

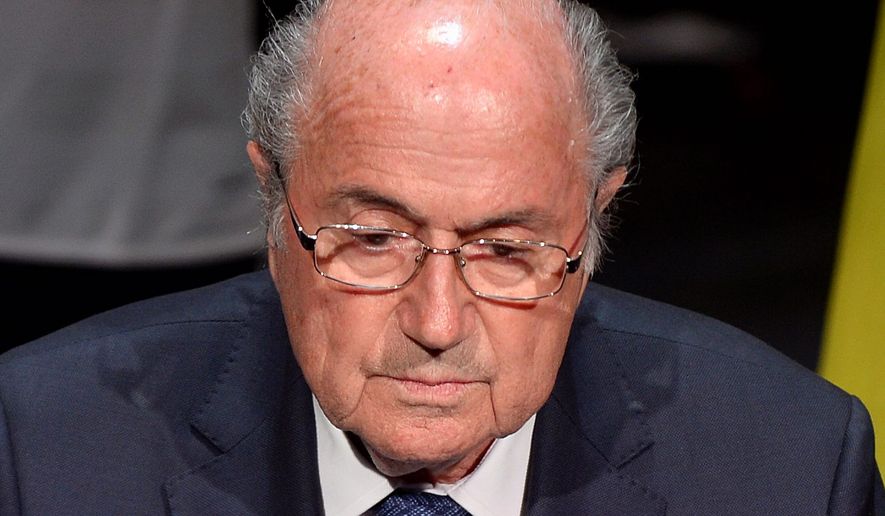

FIFA President Sepp Blatter has been able to keep his position for five terms (he faces a tough Friday vote for a sixth) not through “outright bribes,” according to Mr. Matheson, but by carefully parceling out benefits such as grants and hosting rights to member nations, which in turn influences their vote.

“A $100,000 grant is something that buys a lot of influence in a small soccer power . When you’ve got lots of small players, it’s much easier to buy votes that way,” Mr. Matheson said.

Both Russia and Qatar are now under investigation by Swiss authorities over suspicion of bribery and money laundering in the bidding process for the 2018 and 2022 tournaments, respectively.

Qatar, whose stock market has plummeted in the days following the FIFA arrests, is spending $200 billion on the 2022 tournament, nearly five times more than Germany, Brazil, South Africa and Russia’s costs combined.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.