OPINION:

Adding to the growing momentum in Congress for bipartisan criminal justice reform, last week the Senate Judiciary Committee held a first-of-its-kind hearing to shine much-needed light on pervasive — and largely unexamined — problems in the largest segment of our criminal justice system. Republican Chairman Chuck Grassley of Iowa heard expert testimony describing widespread violations around the country of the Sixth Amendment right to legal counsel for Americans charged with misdemeanors.

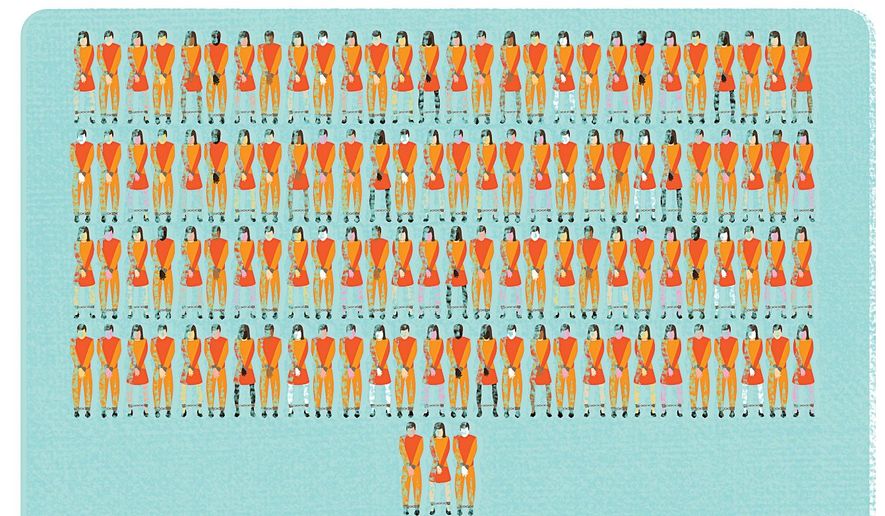

Our nation prosecutes an estimated 10 million misdemeanors each year. Although some misdemeanor offenses criminalize dangerous conduct — such as assault or driving under the influence — most are for far less dangerous, nonviolent conduct, often involving no harm to another person. These include loitering, minor drug possession offenses, and even boating and fishing license violations.

Troubling recent research shows that many state, county and municipal court systems routinely undermine and often directly violate the constitutional right to counsel in misdemeanor cases. In characterizing this evidence, Mr. Grassley stated, “The Supreme Court’s Sixth Amendment decisions regarding misdemeanor defendants are violated thousands of times every day.” No other Supreme Court decisions “have been violated so widely, so frequently, and for so long,” he added.

The evidence backs him up. In Florida, for example, trial courts take an average of just three minutes to find someone guilty of a misdemeanor and impose a criminal sentence at arraignment. In the course of this breakneck “three-minute justice,” judges failed to inform one out of every four misdemeanor defendants of their constitutional right to counsel. Before it was recently amended, a Colorado statute directed prosecutors to speak directly with defendants to try to get them to agree to a plea before they obtained counsel. Another study found that in a single year, 12,000 misdemeanor defendants in Riverside County, Calif., pleaded guilty without a lawyer.

Even when counsel is provided, often the public defender’s caseload is crushing, preventing meaningful legal assistance to many poor people accused of these low-level offenses. Public defense attorneys in multiple cities handle an average of 1,000 misdemeanor cases a year and, in some major cities, up to 2,000. To “handle” this many cases, a lawyer would have time to spend only one hour on each case — for every working hour of the year. Violations of the Constitution are all but guaranteed under such circumstances.

Depriving people of their right to legal counsel can have enormous consequences. As Mr. Grassley noted, for some poor defendants it means serving jail time for asserting their constitutional right. “Defendants who have been locked up pending their first appearance are told that they can plead guilty and be sentenced to time served,” he noted. “But if they choose to be represented by counsel, they will wait in jail until one is appointed.”

In addition to criminal fines, court costs and jail time, a person with a misdemeanor conviction can lose his existing employment and be denied future employment. This can begin a cycle of ongoing employment difficulties and poverty and increase the likelihood of criminal activity as impoverished individuals are deprived of legitimate means of income. One Ohio-based expert testified that in his state alone there are nearly 150 laws denying entire categories of employment to people with a misdemeanor conviction.

To the extent that a person is truly guilty of conduct that deserves to be criminalized, criminal conviction and punishment are appropriate. But when a poor person is unjustly found guilty or pressured into pleading guilty because he is denied constitutionally required legal assistance, the forced unemployment and similar indirect consequences of a conviction greatly increase the injustice.

Last week’s judiciary committee hearing contributes to the movement toward reform in one of the relatively few areas that holds promise of bipartisan action on Capitol Hill. The House Judiciary Committee began holding bipartisan hearings on overcriminalization and related problems in 2009, leading to the formation of the Over-criminalization Task Force — also bipartisan — in 2011. Today, several members of Congress are collaborating across the partisan aisle to create legislative solutions to pressing criminal justice problems.

In a 2011 book he completed just before his untimely passing, Harvard law professor and distinguished criminal justice expert Bill Stuntz stressed the need for our nation’s criminal prosecutions to become more transparent and more responsive to local needs and priorities. Last week’s right to counsel hearing in the Senate Judiciary Committee is an important step toward ensuring democratic accountability and constitutional protections in the 10 million misdemeanor prosecutions around the country each year.

• Brian W. Walsh is president of the Civil Rights Research Center and Virginia Sloan is president of the Constitution Project.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.