ANALYSIS/OPINION:

I recently debated Fox News commentator Judge Andrew Napolitano on the National Security Agency’s 215 program, the massive metadata trove of American calling records used to quickly detect if suspected terrorists have contacted anyone inside this country.

The debate was at CPAC — the Conservative Political Action Conference — which is a hotbed of libertarian energy. For me, representing the “national security state,” it felt like an away game. That Lou Dobbs, Fox News’ resident “independent populist,” was the moderator suggested that even the officiating crew was going to be against me.

Actually, Lou was even-handed, and the Judge and I have a friendship that goes back several years. Still, the event raised some sharp issues.

I surfaced a key one in my opening: “Judge Napolitano is an unrelenting libertarian,” I began, to loud cheers from the audience.

As the cheering subsided, I continued, “And so am I.” I waited a decent interval for the groans and boos to fade and then added, “But for nearly 40 years I had to pay attention to another part of that document, too, the part that says ’provide for the common defense.’”

SEE ALSO: Adan Garar, mastermind of Nairobi Westgate Mall attack, killed by U.S. drone

The point was that this was not, as the Judge and much of the audience would have it, a battle between the forces of light and the forces of darkness. Rather, it was a continuation of a struggle that began with the excesses of George III, followed by a government under the Articles of Confederation that was too weak to govern, followed by a Constitutional Convention to create a stronger central authority, followed by a Bill of Rights to limit that authority.

In short, this is nothing new.

I had a similar discussion at a recent Washington and Lee University School of Law symposium on privacy and security, and my observations there also invited some unkind commentary. Most homed in on my belief that defining reasonableness in implementing the Constitution’s ban on unreasonable search and seizure was dependent on the totality of circumstances in which we find ourselves. I thought that would have been intuitively obvious to anyone who has boarded a commercial airliner in the last 13 years. Apparently it’s not.

Anyone actually responsible for security and privacy has had a working appreciation of reasonableness drilled in to him. I got mine from the legal staff at NSA. Early in my time there they gave me this example: Suppose that we had a legitimate collection point against an important foreign intelligence target. Given the commingled nature of modern communications, a small number of protected (U.S. person) communications occasionally appears, but we have technology that filters out say 90 percent of these so that they are never even recorded. Of course, any inadvertent collection that does occur is destroyed upon recognition.

Important target. Limited inadvertent collection. High technology filter. Reasonable.

But now, my lawyers would tell me in their theoretical example, that we have developed technology that filters out 98 percent. The old system was no longer reasonable. We could do better. The circumstances had changed. Not the Constitution or its ultimate meaning. The circumstances!

SEE ALSO: No charges for man who crashed drone onto White House lawn

At Washington and Lee I admitted that I started to do things differently after 9/11, things that were within my charter and perfectly within my authority, but certainly affected by the death of 3,000 countrymen and the threat of more deaths to follow.

That drew harsh incoming fire.

In The Atlantic: “But if there is a terrorist attack tomorrow, a bureaucrat within the national security state may decide, without asking permission from any elected official, that the people are actually owed less (sic) protections than before.”

Or TechDirt: “To him, the Constitution is a document that he can rewrite based on his personal beliefs at any particular time Specifically, he admits that after September 11th, 2001, he was able to totally reinterpret the 4th Amendment to mean something entirely different.”

Or this elegant blog: “You’re full of xxxx.”

Since Judge Napolitano joined the trashing (not crudely, mind you) I rolled out for him what had actually happened, but not before I warned that accusations fit on a bumper sticker while the truth takes a little longer.

What I actually did had to do with something called minimization. In collecting foreign intelligence, NSA often encounters information to, from or about a U.S. person. It’s inevitable. What the agency does with that is governed by a set of rules approved by the attorney general. In general, when an analyst reports on an intercept with such information, the U.S. identity is suppressed: “In a conversation with named U.S. person number one,” or ” were discussing the policies of named U.S. company number one.”

It makes for clumsy prose, but it protects U.S. privacy. And it’s how it is done UNLESS the U.S. identity is critical to understanding the intelligence in the report. As in, “An individual at a known al Qaeda safe house was discussing attack planning with “

“Named U.S. person number one” doesn’t quite suffice in that one. The name is unmasked in the report.

It’s rarely that easy or clear cut, but NSA analysts and lawyers make that kind of judgment daily. Let me repeat that. Folks at NSA decide if it is reasonable or not to include the U.S. identity. They are usually very conservative, forcing intelligence consumers to formally request unmasking, a process that can be time-consuming. It was an approach that, if continued in the immediate aftermath of 9/11, would certainly protect NSA from future bloggers, but would be less effective in protecting America.

So, acting within my charter and my authority, based on the totality of circumstances, I directed NSA analysts to lean forward in unmasking U.S. identities in their original reporting on communications entering or leaving Afghanistan. I then told the White House and the Congress what I had done.

So that’s it. No bonfires of “The Federalist Papers” or of the Constitution. At CPAC I admitted that some in the audience would still find what I did objectionable, but added, “It ain’t exactly the British army grabbing Boston Common.”

People can disagree with choices. This is hard stuff. The facts are complicated and the law is contentious. Even with my best effort, I admit I am capable of getting either or both wrong. But that doesn’t mean folks like me should be casually dismissed.

Defaulting to slogans and ad hominem attacks protects neither our liberty nor our security.

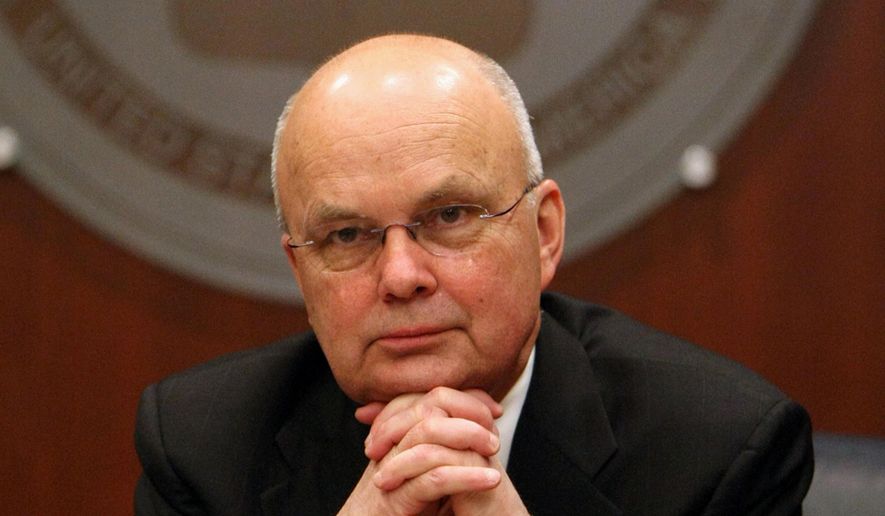

• Gen. Michael Hayden is a former director of the CIA and the National Security Agency. He can be reached at mhayden@washingtontimes.com.

• Mike Hayden can be reached at mhayden@example.com.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.