In the days after linebacker Chris Borland’s retirement, former players and sports pundits around the country have wondered about the future of football.

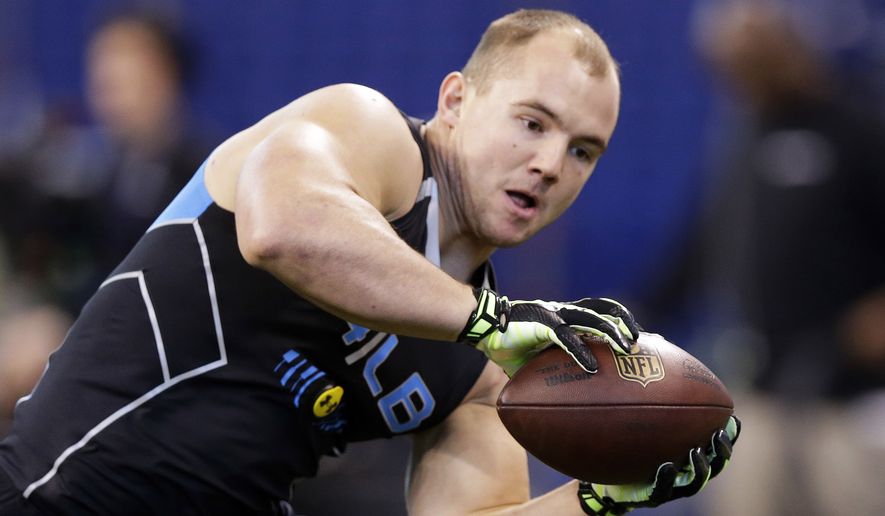

Borland was a third-round pick with a bright future. He made 107 tackles for the San Francisco 49ers as a rookie. He had no medical issues, but after researching the impact of concussions on NFL players, his concern prompted him to quit Monday at 24 years old rather than go on.

Across the country, in Gambrills, Maryland, Diondre Wallace was shocked by the news. A senior at Arundel High School and one of the area’s top high school linebackers, Wallace had followed Borland’s budding career, watched him play and can recite some of his past awards and credentials on the spot. Borland’s decision, however, did not affect him.

“It’s a big risk, but I’m aware of it,” said Wallace, who has played for the United States U-18 national team and will play at Towson in the fall. “You know what you sign up for. We all do.”

In the high school football community, the effects of Borland’s decision have hardly been noticeable. Coaches believe Borland’s retirement is yet another indicator that football needs improved safety measures at all levels, not a harbinger of doom for the sport. Players, many more informed than their predecessors, will continue their personal risk-reward assessments.

“It’ll change the game a little bit. I don’t think it’s going to change it as much,” Wallace said. “For me, football is something I love because it was my way through a lot of adversity. It was my vehicle through a lot of things in my life. I grew up in a family where we didn’t really have much, and I’m one of the kids in my family that can say I’m going to college. I have an opportunity, possibly, in the future to go to the NFL. That’s why I keep pushing. Because I know that there’s something greater out there for me.”

SEE ALSO: LOVERRO: Greater the injury risk, greater the fear for parents after Chris Borland retires

According to the National Federation of State High School Associations, participation in high school football actually increased between 2012 and 2013 for the first time in five years. Though numbers are slightly down in the country’s largest hotbeds — California, Florida and Texas among them — they have remained largely consistent in recent years, despite increasing research about concussions and recent deaths of football players attributed to repeated blows to the head.

Coaches believe the culture of high school football has been evolving for several years now. Northwest High School coach Mike Neubeiser, whose team has won back-to-back Maryland 4A state championships, said the atmosphere in the sport has changed in recent years and shifted dramatically since his playing days in the early 1990s. For example, said he was only “officially” diagnosed with one concussion in high school.

“If you got ’dinged up,’ as people would say, you saw stars and you just kind of kept playing through it. And if you didn’t, you weren’t tough enough to play football, that type of thing,” said Neubeiser, who went on to start at linebacker for Wake Forest. “Now, we constantly talk to kids about how they’ve got to let us know. There’s tests when kids come to sidelines, if they don’t look right, if there’s any indication whatsoever that there’s any possibility of a concussion, they’re immediately seen by a physician or a trainer.”

In high school today, there are also players like Wallace, who, when asked about head trauma, cite recent research and speak eloquently about the dangers of second-impact syndrome.

Wallace said he only had one concussion, in seventh grade, and has since researched the potential dangers of the sport. He reads about the issue online and flips through recent studies suggesting that strengthening neck muscles could help prevent concussions. He said he has also consulted several college and NFL players about head trauma.

In San Mateo, Calif., Scott Altenberg coaches a Junipero Serra High School football program that has produced numerous Division I and NFL players, including Buffalo Bills wide receiver Robert Woods and Washington Redskins safety Duke Ihenacho. He feels not all high school players are as understanding of the risks.

“I don’t think the kids get it yet,” Altenberg said. “I don’t think they’re old enough. They still think they’re bulletproof at this age.”

Altenberg said Borland’s retirement reminded him of UCLA linebacker Patrick Larimore, who medically retired because of repeated concussions in 2012. Larimore’s departure from football was met with similar surprise and questions. He went on to start a website, MyHeadHurts.co, to provide a forum for others who have suffered head trauma.

Last season, Altenberg and his staff forced one of its starting guards, senior Jerone Burke, to medically retire because of numerous concussions. Awareness of the dangers has grown in the state, he said, because illegal hits are relentlessly flagged and proper tackling is mandated at the high school level.

Altenberg believes the youth level is the source of much of the sport’s safety issues. More than half of youth leagues in the country have implemented the “Heads Up” program, according to USA Football spokesman Steve Alic, but there is still much to be done. The sport is not as safe as some, like Dr. Joseph Maroon, the Pittsburgh Steelers’ neurosurgeon and a consultant of the NFL’s Head, Neck and Spine Committee, believe it to be.

“It’s never been safer,” Maroon told NFL Network on Wednesday. “It’s much more dangerous riding a bike or a skateboard than playing youth football.”

Altenberg disagrees. He has two football-crazed sons, Luke and Nate, who are 10 and 7 years old. Before signing them up for a Pop Warner league, he attended three different practices and was appalled by how frequently the kids were hitting one another. Altenberg now says he will not allow his sons to play football.

“Not until I see the Pop Warners of the world change it,” he said.

Wallace will leave for Towson this summer, still dreaming about his NFL shot. Altenberg still wonders what’s best for his kids, both those he coaches and the two under his roof. Borland made his individual decision Monday. The decision to play football remains largely personal, and no one individual choice has changed that.

• Tom Schad can be reached at tschad@washingtontimes.com.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.