OPINION:

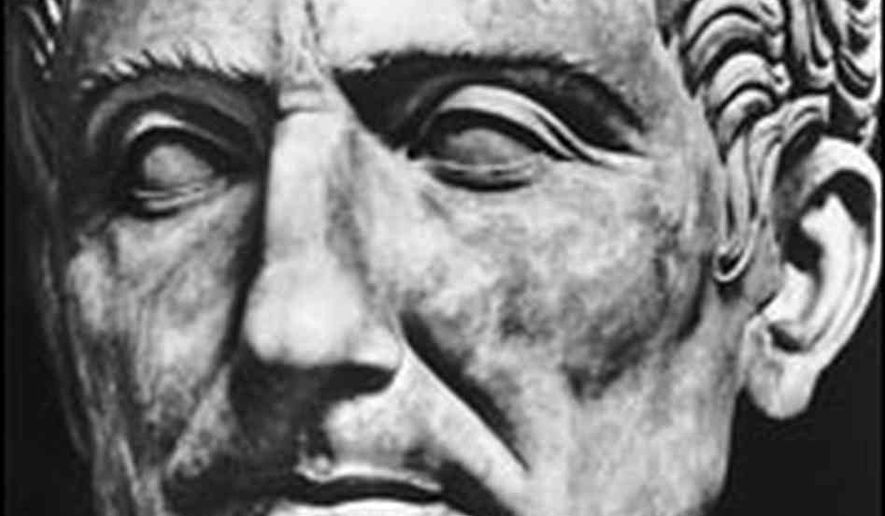

This just in! William Shakespeare got his facts wrong about the death of Julius Caesar.

That is only part of an excellent book, “The Death of Caesar,” by Cornell history and classics professor Barry Strauss, who read ancient texts and retraced Caesar’s steps. The volume also provides important insights for the public, the media and politicians.

But first the facts. The assassination of Caesar by some 60 conspirators occurred in 44 B.C. in the Portico of Pompey during a session of the Roman Senate.

At the time of Caesar’s death, Rome was hardly a place of grandeur. Mr. Strauss compares the city to “Al Capone’s Chicago and Boss Tweed’s New York.” Moreover, Caesar wasn’t the grand man history has made him. As Mr. Strauss puts it, “All his life Caesar loved risk and embraced violence.”

Although Shakespeare’s work was a play — somewhat similar to today’s films inaccurately portraying facts, which have become what many people believe happened — Mr. Strauss has corrected some of these flaws.

For example, Mr. Strauss maintains that no one actually said, “Beware the Ides of March are upon us.”

Caesar had visited a soothsayer who warned him he would be harmed during a month’s time, or by March 15, the day he was assassinated. Neither did a dying Caesar say, “Et tu, Brute?”

The author also writes that Shakespeare erroneously referred to Marcus Junius Brutus. But Mr. Strauss makes a convincing argument that another Brutus played a significant role in the murder.

He was Decimus Junius Brutus Albinus, or Decimus, a onetime confidant of Caesar’s who was upset that the dictator had passed him over for advancement. Shakespeare actually misspelled his name as “Decius” and gave him a minor role in the assassination.

Decimus, Mr. Strauss argues, was the inside man for Gaius Cassius Longinus (Cassius, in the play) and the play’s Brutus. “Decimus was a liar,” Mr. Strauss writes, “a flimflam man, a brazen and audacious snake. In short, he was much like Caesar.”

So what can the public, the media and politicians learn from the errors in Shakespeare and Mr. Strauss’ bid to correct them?

Like Shakespeare’s play, the recent motion pictures “Selma” and “American Sniper” provide interesting, yet inaccurate, episodes to move the action along.

“Moviegoers want a clear and simple storyline and real-life, human characters,” Mr. Strauss said in an interview. “Historians can’t deliver the first without distorting the complexity of events, but we can provide the second. We can write about the passions and experience of people in the past who were once every bit as alive as we are.”

Back in ancient Rome, like Washington, spin played an important role in the perception of Caesar and those involved in his death.

“The spinners write history,” Mr. Strauss told me. Octavian, who became Augustus Caesar, portrayed Decimus as the chief betrayer of Caesar back then. As the history of the period was written, however, Octavian made certain that Decimus was ignored.

What could Caesar, the politician, have done to avoid his assassination?

“No politician can get away with breaking all the rules. No politician, no matter how successful, can afford to tick most people off,” Mr. Strauss added. “The safest course for Caesar would have been to lower his ambitions, restore the republic and lead a quiet life, but Caesar wasn’t about to do that.”

Although “The Death of Caesar” deals with events long past, today’s politicians might want to heed the warning: Beware breaking the rules and ignoring the public — not just on the ides of March but throughout the year.

• Christopher Harper is a longtime reporter and former Rome bureau chief for ABC News who teaches journalism at Temple University. He can be contacted at charper@washingtontimes.com and followed on Twitter @charper51.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.