BAGHDAD (AP) — Tariq Aziz, the debonair Iraqi diplomat who made his name by staunchly defending Saddam Hussein to the world during three wars and was later sentenced to death as part of the regime that killed hundreds of thousands of its own people, has died in a hospital in southern Iraq, officials said. He was 79.

Aziz died on Friday afternoon after he was taken to the al-Hussein hospital in the city of Nasiriyah, about 200 miles (320 kilometers) southeast of Baghdad, according to provincial governor Yahya al-Nassiri. Aziz had been in custody in a prison in the south, awaiting execution.

Aziz was the highest-ranking Christian in Saddam’s regime was the international face of Saddam’s regime for years. He was sentenced in October 2010 to hang for persecuting members of the Shiite Muslim religious parties that now dominate Iraq.

A Baghdad government official confirmed the death of Aziz. He spoke on condition of anonymity because he was not authorized to talk to reporters.

The only Christian among Saddam’s inner circle, Aziz’s religion rescued him from the hangman’s noose that was the fate of other members of the top regime leadership.

After he was sentenced to death, the Vatican asked for mercy for him as a Christian. Iraq’s president at the time, Jalal Talabani, then refused to give the death sentence his required signature, citing Aziz’s age and religion.

But even before the death sentence, the ailing Aziz appeared to know that he would die in prison. He had had several strokes while in custody undergoing trial multiple times for various regime crimes.

“I have no future. I have no future,” Aziz told The Associated Press, looking frail and speaking with difficulty because of a recent strokes, in a jailhouse interview in September 2010. At that stage, he had been sentenced to more than two decades in prison.

“I’m sick and tired but I wish Iraq and Iraqis well,” he said.

Elegant and eloquent, Aziz spoke fluent English, smoked Cuban cigars and was loyal to Saddam to the last, even naming one of his son’s after the dictator. His posts included that of foreign minister and deputy prime minister, and he sat on the Revolutionary Command Council, the highest body in Saddam’s regime.

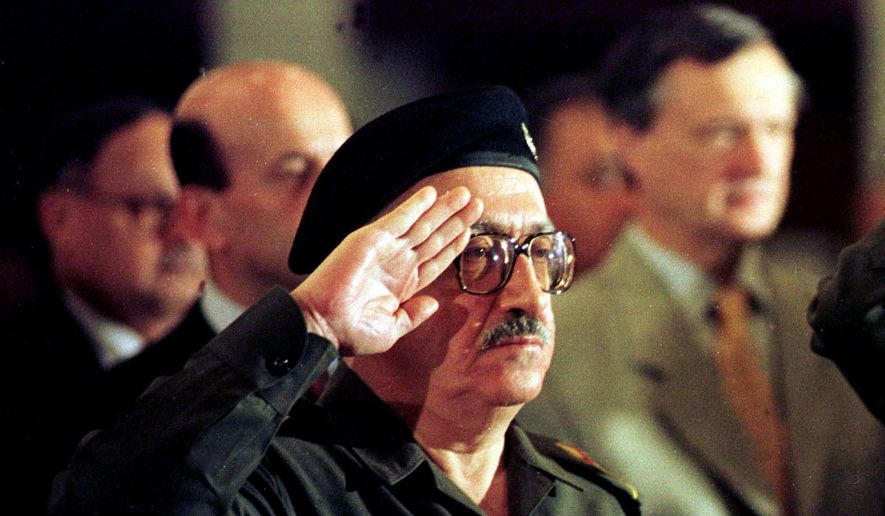

His main role was as the regime’s go-to man to communicate with the West. To the world, he was one of the most recognizable faces from Iraq during Saddam’s rule: silver haired, with a mustache and trademark dark-rimmed glasses. A skilled operator in the halls of the United Nations, he was the regime’s front-man in dealing with U.N. inspectors trying to track and assure the dismantling of Saddam’s weapons of mass destruction.

His interlocutors variously described him as courtly, articulate, arrogant and unhesitant to make even the most preposterous denials of evidence put before him by inspectors about weapons programs.

“He didn’t agree with our basic tasks and I didn’t agree with his tasks to hide and mislead us. But I think we respected each other,” Rolf Ekeus, head of the inspectors from 1991 to 1997, later said of Aziz.

As bombs rained down on Baghdad during the U.S.-led 2003 invasion, Aziz said of American forces, “We will receive them with the best music they have ever heard and the best flowers that have ever grown in Iraq … We don’t have candy; we can only offer them bullets.”

His freedom ended shortly afterward. The U.S. military knocked on his door in Baghdad on April 24, 2003, and he surrendered without resistance.

Still, his prominence as an international spokesman — and his outsider status as a Christian in a Sunni Muslim-dominated regime — gave supporters fuel to argue that he was not a real decision-maker in Saddam’s regime and was less to blame in the torture and bloody crackdowns it inflicted on Iraqis.

Aziz was born to a Chaldean Catholic family in Tell Kaif, Iraq, in 1936. He studied English literature at Baghdad College of Fine Arts and became a teacher and journalist. He joined the Baath Party in 1957, working closely with Saddam to overthrow British-imposed monarchy.

Saddam took charge in 1979. Aziz was deputy prime minister a year later, when attackers hurled a grenade at him in downtown Baghdad. Several people were killed; Aziz was injured. It was one of several attacks Saddam blamed on Iran — part of his justification for the expulsion of large numbers of Shiite Muslims and Iraq’s 1980 invasion of Iran.

Aziz was instrumental in restoring diplomatic relations with the United States in 1984, after a 17-year break. At the time, Washington backed Iraq as a buffer against Iran’s Islamic extremism.

That changed after Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait in 1990. Aziz met in January 1991 with then-Secretary of State James A. Baker in Geneva in a failed attempt to prevent the Gulf War, and the U.S. broke off ties with Saddam’s government for good. He also met with the late Pope John Paul II at the Vatican just weeks before the March 2003 invasion in a bid to stop it.

Years later in court, Aziz again defended Saddam.

A star defense witness for his former boss in 2006, a thin and pale-looking Aziz in checkered pajamas — a far cry from the designer suits he once sported — insisted Saddam had no choice but to crack down in the Shiite town of Dujail after a 1982 shooting attack on the president’s motorcade there blamed on Shiite opponents.

“If the head of state comes under attack, the state is required by law to take action,” said Aziz.

And in the trial of six former Saddam officials charged with the 1980s crackdown on Kurds that killed an estimated 100,000 people, Aziz claimed, “There was no genocide against the Kurds … Those defendants were honest officers who defended their country and fought Iran.”

Aziz himself stood trial in seven cases — nearly all on charges of crimes against humanity related to Saddam’s campaigns against Shiite political parties and Kurds. He was convicted in all but two, and sentenced to death by hanging in October 2010 for his involvement in the former regime’s bloody persecution of Shiites.

As his death verdict was read in court, Aziz sat alone and quiet, and grasped a handrail surrounding the defendant’s box. By that time, he had suffered a stroke in jail that had left him badly weakened and temporarily mute.

But even as he was ordered executed, Aziz gained a powerful diplomatic ally. The Vatican asked that Aziz’s life be spared, saying mercy would encourage reconciliation and the rebuilding of peace and justice in Iraq. The Vatican’s plea picked up support among several other European diplomats from nations that also oppose the death penalty — though few had made much pressure to stop earlier executions of other, Muslim members of Saddam’s regime.

Aziz’s wife, Violet, and two sons, Ziad and Saddam, who live in Jordan and survive him, had lobbied he be allowed medical treatment outside Iraq. Ziad Aziz said his father had long suffered from diabetes and high blood pressure, but his health took a turn for the worse shortly before the 2003 invasion.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.