As the U.S. and its world partners race to reach a nuclear deal with Iran, women and children in the Islamic republic struggle under harsh, discriminatory laws despite numerous calls for reform from human rights groups and the international community.

Last year, several women in the Iranian city of Isfahan were severely burned in acid attacks. The women were rumored to have been targeted for not being properly veiled.

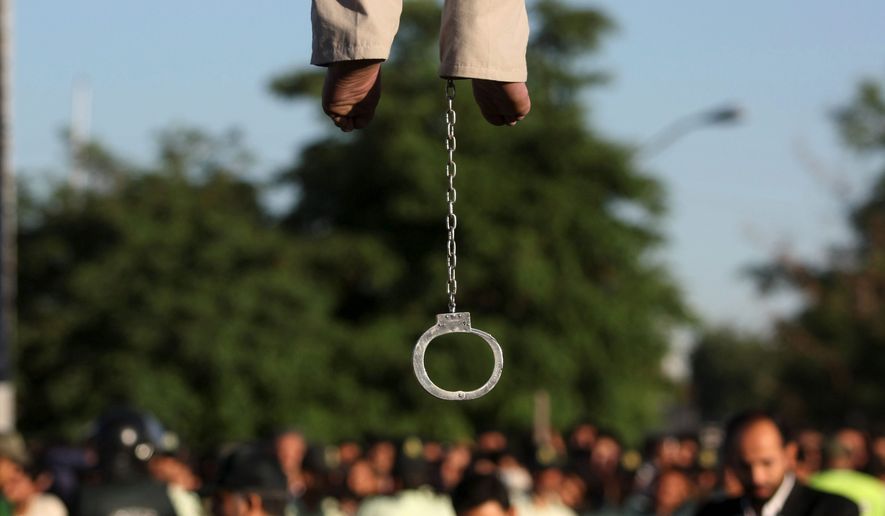

Meanwhile, children are subject to the death penalty in Iran, and the rate of executions of minors has increased in the past two years under “moderate” President Hassan Rouhani, according to Human Rights Watch.

U.N. Secretary General Ban Ki-moon, in his report to the United Nations General Assembly this year, said at least 160 children are serving time on Iran’s death row.

In addition, tens of thousands of children, both Iranian nationals and undocumented immigrants, are forced into prostitution in Iran, say government and nonprofit human rights researchers.

But according to the latest Human Rights Report released by the Department of State, the Iranian government has done little to improve the plight of women and children.

“The government took few steps to investigate, prosecute, punish, or otherwise hold accountable officials, whether in the security services or elsewhere in the government, who committed abuses. Impunity remained pervasive throughout all levels of the government and security forces,” the State Department report reads.

The United Nations in 2011 appointed a special rapporteur on human rights in Iran, but rapporteur Ahmed Shaheed has not been allowed to enter the country to conduct reviews.

In Washington, Congress has passed several resolutions condemning human rights abuses in Iran, but those nonbinding resolutions have been met with little to no response from the Iranian government.

Human rights analysts say the abuses against women and children in Iran have increased in recent years.

“In general, the human rights situation has not improved and has remained pretty dire and in certain situations it has gotten worse,” said Faraz Sanei, an Iran researcher at Human Rights Watch.

Mr. Sanei said most countries have taken steps to reduce executions, especially for children, but the numbers have increased in Iran, a trend he called “particularly disturbing.”

Last year, Iran executed at least 289 people, according to Amnesty International, making the Islamic republic the world’s second most prolific practitioner of capital punishment. China, whose data are kept as state secrets, is believed to execute thousands of people each year. The U.S. conducted 35 executions last year, according to the Death Penalty Information Center.

According to Amnesty International, Iran may have executed as many as 77 minors over the past 10 years for crimes committed before the age of 18, a violation of international human rights laws.

Mr. Sanei said that even though Iran has signed the Convention on the Rights of the Child, an international human rights treaty that prohibits capital punishment for those younger than 18, Iranian officials say any provision that contradicts Shariah law is null and void in the country, allowing the courts to continue to carry out executions.

According to the State Department report, Iranian law permits executions of individuals who have reached puberty, which is defined as about 9 years old for girls and about 15 for boys.

Mr. Sanei said the charges against children convicted in Iran often would not be considered malicious or intentional in the U.S. or European countries, and therefore not worthy of the death penalty.

“For example, you have cases where two children have gotten into a street fight and in the heat of the moment one child stabs another. That’s not premeditated murder,” he said.

After the revolution

Iran also has a huge child trafficking problem that has raised concerns among human rights groups, the Department of State and the United Nations.

According to the Department of State’s latest country report on human trafficking, which rates Iran as one of the worst offenders, “Iran is a source, transit, and destination country for men, women, and children subjected to sex trafficking and forced labor.”

As many as 50,000 children — some as young as 4 — are forced by their parents or well-organized criminal networks to beg in the streets of the capital city of Tehran, according to the State Department report, which was compiled from data and reports of various human rights groups. Many of the children are forced to sell drugs, work in sweatshops or enter into prostitution.

Children in Iran are at a higher risk of having stateless status because women cannot transfer their Iranian citizenship to children who are not born to Iranian fathers.

Iranian Foreign Ministry spokeswoman Marzieh Afkham on Friday slammed the State Department’s claims in its annual report as “baseless” and “repetitive,” and accused the U.S. of hypocrisy, given its own human rights abuses.

“Many instances of human rights violations in the U.S. including police brutality, widespread discrimination against African-Americans, discrimination against refugees, the increase of anti-Islamic sentiments and restricting religious minorities, as well as Washington’s unconditional support for Israel’s crimes, have drawn criticism from major international rights institutions and as such have rendered the concerns raised in the U.S. report as unbelievable,” Ms. Afkham said, as reported by Iran’s MEHR news agency.

Immigrant children, especially girls, are more vulnerable to being caught up in the sex trade because Tehran does little to aid unaccompanied minors, and in many cases those children traveling from Afghanistan looking for work are severely abused in detention centers.

Haleh Esfandiari, director of the Middle East Program at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, said most of the rights that Iranian women fought to obtain before the 1979 revolution were lost after Iran’s Shiite theocracy took control of the government and society.

“Women hoped that the revolution would improve their rights, but very soon in the game they found out this was not the case,” Ms. Esfandiari said. “The revolution that they loved did not love them back.”

Ms. Esfandiari said the age of marriage dropped from 18 to 9 after the revolution. Since then, that age has been increased to 13, but a law enacted in 2013 allows Iranian men to marry their adopted daughters, a move that critics say legalizes pedophilia.

Under post-revolution laws, a woman cannot seek a divorce from her husband unless he signs a contract to allow it, cannot provide for his family, or is a drug addict, insane or impotent, according to the Department of State report.

A husband is not required to cite a reason for divorcing his wife, and in court, a woman’s testimony is worth only half as much as a man’s.

As women now are outnumbering men in universities in Iran, Mr. Sanei said, the government has taken steps toward “gender engineering” certain fields by making some courses unavailable to women.

“They said, ’If you want to become an electrical engineer, we are going to provide five slots for women and double that for men,’” he said. “It creates restrictions for what women can do, and lots of those jobs are the ones that are the most competitive and the most marketable.”

Mr. Sanei and Ms. Esfandiari said many of the human rights abuses against women and children are out of Mr. Rouhani’s hands, citing the culprit of the abuses as Iran’s judicial system and the security forces, which do not answer to the government.

“Under Rouhani, the status of women, the participation of women has improved, the social sphere has also improved, there is less harassment on the streets. But when it comes to human rights issues, the government doesn’t have much of a say. It’s the judiciary, which does not even bother to listen to the Cabinet or to Rouhani, and it is the security agency,” said Ms. Esfandiari, who was arrested by Iranian security forces in 2007 and held in solitary confinement in Tehran’s notorious Evin Prison for 105 days.

But there are some areas where the government could do more to help relieve the hardships that women and children face, and one of the simplest ways Mr. Rouhani could do so would be to appoint women to Cabinet positions, as he promised during his campaign, human rights observers say.

“One thing that we were hoping would happen is that under Rouhani we would get a woman Cabinet member. That has still not happened,” Mr. Sanei said. “There is a vice president for women and family affairs, but that’s not technically a Cabinet position, but it is an adviser to the president.”

That vice president, Shahindokht Molaverdi, has been outspoken on women’s issues, and she even lashed out against the government after it reneged on its promise to allow most women to attend an international men’s volleyball match last week and condemned “sanctimonious” religious groups that threatened violence against the few women who did attend.

Mr. Rouhani also has made some progressive statements about women’s rights that have drawn harsh criticism from hard-liners in Iran.

“One cannot take people to heaven through force and a whip,” Mr. Rouhani said in May 2014, suggesting that force is not productive in promoting conservative cultural values.

Iran’s supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, recently called for universal primary education for all children, even undocumented immigrants, an idea that has met harsh resistance in the country.

Despite such hopeful statements, the fact remains that Iran has done almost nothing to work with human rights groups, barring the U.N. special rapporteur on human rights and almost all other rapporteurs on other issues.

“They haven’t responded very well to demands for improvements. It’s been atrocious on very many levels,” Mr. Sanei said. “There is a lack of cooperation by the Iranian government in terms of working with human rights bodies.”

The Iranian narrative generally has been that human rights are a political issue and that the U.N. should focus on countries that have committed worse atrocities, but they continue to refuse to cooperate with the U.N. mandate to allow access to the special rapporteur.

Although U.S. officials have stressed that the nuclear negotiations are strictly focused on nuclear programs, some human rights analysts and lawmakers are concerned that the U.S. could concede non-nuclear sanctions in order to reach a deal with Iran, a move that could have consequences for human rights efforts.

In a June 22 interview on MSNBC’s “Morning Joe,” Sen. Bob Corker, Tennessee Republican and chairman of the Senate Committee on Foreign Relations, said, “It appears the administration may be considering negotiating a way more than just the nuclear-related sanctions but trying to tie others to it.”

Such a move, he said, would be “very concerning.”

Ms. Esfandiari said human rights may be discussed in one-on-one discussions between diplomats on the side of the nuclear talks. She said she hoped a deal would open the door to more discussion on human rights issues but acknowledged that it would be difficult to get Iran to cooperate.

“Once we have a deal and if the relations between the two countries improve and if the relations between Iran and the European countries improve, then I’m sure those countries will start bringing pressure on them, but will Iran let the special rapporteur in? I don’t think so. I don’t think Rouhani even has a say in that,” Ms. Esfandiari said. “Once he is allowed in, he will visit the prisons and he will give a scathing report.”

• Kellan Howell can be reached at khowell@washingtontimes.com.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.