OPINION:

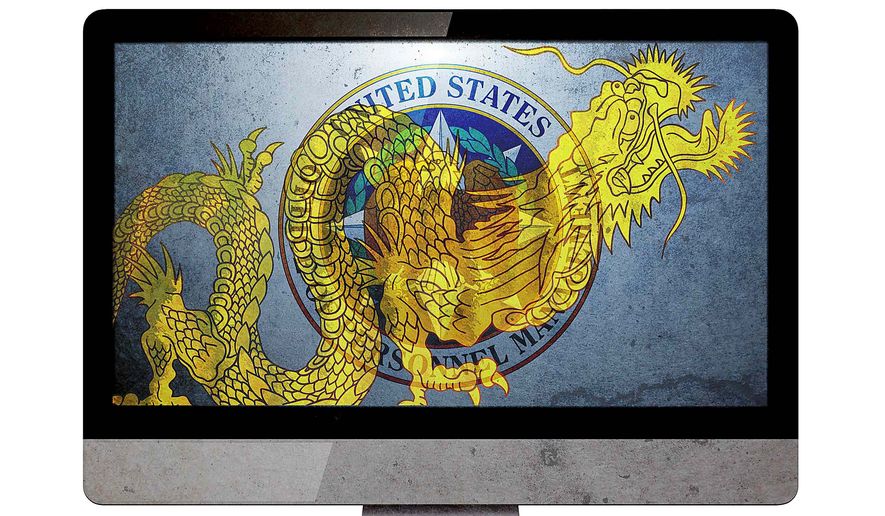

On June 4, the media reported that for the second time in a year, the Office of Personnel Management’s computer network was the target of a successful penetration by the People’s Republic of China. It now appears that OPM was aware of the cyber-espionage attack for more than a year without remedying its vulnerability.

That OPM had left itself vulnerable to cyber-espionage by China (and the rest of the world) for so long was evidence of an extreme level of incompetence and negligence. Last year, an OPM contractor — a company called USIS that had been doing background investigations for security clearances under contract with OPM — had its records invaded by cyberattack. (USIS apparently fit in with OPM’s evident incompetence. It had vetted and passed for security clearances both infamous National Security Agency leaker Edward Snowden and Aaron Alexis, who shot and killed a dozen people at the Washington Navy Yard).

OPM was apparently surprised that China would hack into its computer networks. I wasn’t shocked — and certainly not amused — by the letter I received from OPM early last week. It informed me that my personal information, which OPM has kept and apparently updated since I last served in government, may have been “compromised” in the event.

The letter said, in part, “You are receiving this notification because we have determined that the data compromised in this incident may have included your personal information, such as your name, Social Security number, date and place of birth, and current or former addresses.” I’m apparently supposed to take comfort in the fact that, as the letter said, I’d have — until December 2016 — $1 million in identity theft insurance, paid for by Uncle Sam as well as “a complimentary subscription to CSID Protector Plus,” a contractor-provided identity protection service until that same date.

The last time I served in government was in 1990-91, when I was a deputy undersecretary of defense. I had some pretty fancy security clearances then, but haven’t had an active clearance since. This indicates that the Chinese have gained at least 25 years’ worth of security clearance information on the millions of Americans who have had clearances.

Anyone who has filled out the paperwork for a high-level security clearance knows that the information includes a lot more than Social Security numbers and addresses. It also contains job histories, names of friends and family, and information on personal finances. In short, it’s more than enough to falsify the person’s identity.

And that’s hardly all. If the data were compromised, it’s entirely possible that they were modified to suit the purpose of the hackers. Mucking around in government databases doesn’t just mean copying information that shouldn’t be disclosed. There’s every reason to believe the same information could be changed for whatever purpose the cyberspy desires.

In this case, the hacker is almost certainly the People’s Republic of China. OPM and the rest of the federal bureaucracy is shocked, simply shocked, that China would do such a thing. Seriously?

The real shock is that OPM — and many other federal agencies, including the Pentagon and the White House — are still unprepared to deal with the Chinese (and Russian) cyber-espionage programs that has been going on for almost 20 years.

It goes back at least to March 1998. Then, apparently by accident, we discovered that the Pentagon, NASA and the Energy Department (which has joint authority with the Pentagon over nuclear weapons) were all penetrated by Russian hackers in a series of events we code-named “Moonlight Maze.” The details of those attacks are still classified.

Organized and operating since at least 2003 (and possibly five years earlier) were the Chinese cyber-espionage attacks labeled “Titan Rain.” These were a massive series of cyber-espionage penetrations of the defense and intelligence communities by the People’s Liberation Army’s then-new cyberwar center in Guangdong Province.

The record of Chinese and Russian cyber-espionage directed at American defense, intelligence and defense industry networks is long and consistent. It is, and has been for years, the most dangerous cyber-espionage effort against us, responsible for the theft of advanced technologies costing billions to develop.

Cyberspy attacks on U.S. government networks, which used to occur frequently, now happen literally hundreds of times a day.

Only a small fraction of these cyber-espionage efforts become public, such as the June 2007 cyberattack by the Chinese, who gained access to the Army’s unclassified email system in the Pentagon. Or the 2012 incident in which the Chinese possibly gained access to top-secret White House computer systems that communicate with the military regarding nuclear weapons. (Russian cyberspies penetrated unclassified White House information from October 2014 to May of this year.)

We hear about only a small fraction of these attacks because government agencies don’t want to advertise their vulnerability to the American public, though it must be widely known to our adversaries. On that record, for OPM to remain as vulnerable as it has been demonstrates a level of incompetence and negligence that is unusual even in our government.

Defending against cyberspies is hard and costly. Malware — the kind of software used to penetrate computer networks to spy on or sabotage them, or both — changes so fast that serious guardians against these attacks have to come up with new counterprogramming almost every day. And they do. Many specialists are hard at work in government and industry blocking and detecting attacks, and creating firewalls to protect our military, intelligence and industrial networks at an annual cost of several billion.

OPM — having existed in blissful vulnerability — appears to have achieved an extraordinary level incompetence. That cannot be tolerated. Heads should roll at OPM, and anywhere else that our secrets remain vulnerable to cyber-attacks.

• Jed Babbin was deputy undersecretary of defense in the George H.W. Bush administration and is co-author of “The Sunni Vanguard” (London Center for Public Policy, 2014).

Please read our comment policy before commenting.