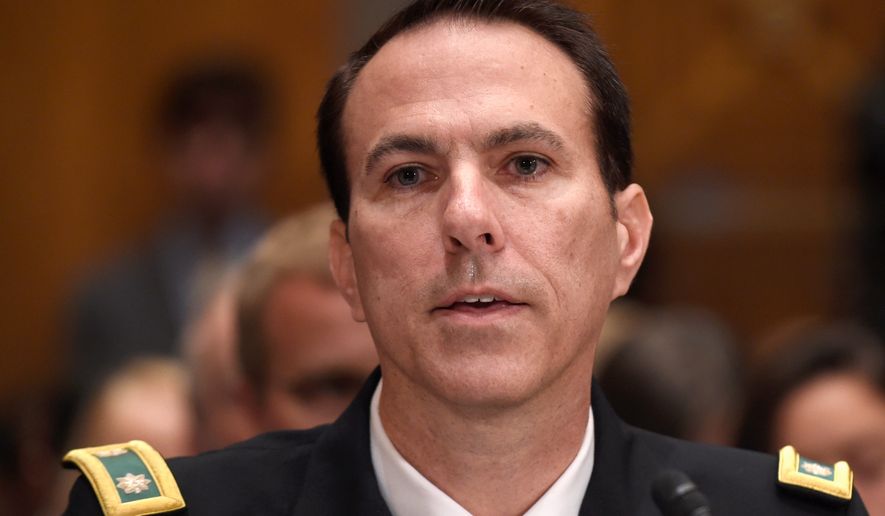

When Lt. Col. Jason Amerine, a decorated Green Beret, took the big step last summer of contacting a member of Congress on the gnawing question of freeing American hostages, he never suspected the bureaucratic minefield that awaited him, especially from the FBI.

The decision proved just as life-changing as his prominent role in the 2001 invasion of Afghanistan and the famous union of a young A-team captain and future Afghan President Hamid Karzai.

Col. Amerine now finds himself banished from the Pentagon, where he sought to shake up the Obama administration to do a better job of rescuing captives.

In the spotlight last week, he told a Senate panel that he, in effect, feels betrayed by the FBI, which he said filed false accusations against him with his Army superiors. A congressional staffer said the FBI played hardball in a turf battle to force the officer “back into his lane.” Col. Amerine believes the Army is bent on court-martialing him once the Criminal Investigation Command finishes its probe.

His exile has its roots in his frustration with what he considered a “dysfunctional” hostage-freeing process scattered among multiple agencies, including the FBI, the Pentagon and the State Department.

He began a communications stream with a man known for action, Rep. Duncan Hunter, a California Republican and former Marine officer who has gone to bat for a number of service members he believed were mistreated by the top brass.

Out of those discussions came progress. Mr. Hunter persuaded the Pentagon to appoint a senior civilian to oversee hostage negotiations or military actions. He is winning votes for a bill that would direct the administration to appoint a hostage czar. The White House agreed to review the entire process whose flaws, Republicans say, became obvious when President Obama traded five Taliban chieftains for one Army sergeant — Bowe Bergdahl, an accused deserter.

In the course of trying to jolt the system, Col. Amerine became a casualty. Mr. Hunter set up a meeting for him with FBI officials last summer. The officer later described the meeting as “cordial.”

But the next thing he knew, the FBI filed a formal complaint with Army headquarters, accusing him of sharing classified information with Mr. Hunter, a member of the House Armed Services Committee.

In January, the Army escorted him from his office, stripped his security clearance, stuck him in a desk job in Crystal City and unleashed a criminal investigation.

Mr. Hunter’s staff viewed it as the kind of snafu that could have been worked out inside the Army. Instead, Joe Kasper, chief of staff, said the Army is getting back at the congressman for the battles he has waged against a defective intelligence network system and on behalf of soldiers punished by Army Secretary John McHugh.

At last week’s hearing before the Senate Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs Committee, Mr. Hunter seated himself directly behind the Green Beret at the witness table.

The officer testified that he believed the Army was violating his rights under the Military Whistleblower Protection Act.

He told of having high hopes that the FBI would join him in consolidating the hostage-freeing business.

“I continued to work with Rep. Hunter’s office to repair our dysfunctional hostage recovery efforts,” he said. “He set up a meeting between my office and the FBI. The meeting appeared to be cordial, but the FBI formally complained to the Army that information I was sharing with Rep. Hunter was classified. It was not.”

Then Col. Amerine told of the FBI’s motive. Basically, it did not like him playing on its turf.

“After my criminal investigation began, the FBI admitted to Rep. Hunter that they had the utmost respect for our work but they had to put me in my place,” he testified. “Again, the FBI made serious allegations of misconduct to the Army in order to put me in my place and readily admitted that to a U.S. congressman.”

An FBI spokesman at Washington headquarters declined to comment to The Washington Times.

Its complaint sparked political intrigue inside Army headquarters as officials debated what to do with Col. Amerine, one of its better-known soldiers who was awarded the Purple Heart and Bronze Star, with a combat V for valor, for leading his troops on a drive to Kandahar.

He testified that “one party” in particular wanted him investigated.

A source said he identified that officer as Lt. Gen. Mary A. Legere, head of Army intelligence, in a complaint to the Pentagon inspector general. She had butted heads with Mr. Hunter on the service’s development of a faulty intelligence computer network.

Grating the FBI further was the fact that during Mr. Hunter’s communications with Col. Amerine, the congressman accused the administration — thus the FBI — of paying ransom for Sgt. Bergdahl. He asked the inspector general to investigate.

“So part of what lit the fuse was the same folks in the FBI that were basically implicated in the DOD I.G. complaint of 1 December were the ones that later complained to the Army that I was sharing sensitive information with Representative Hunter,” Col. Amerine said. “Another aspect of it on the FBI’s side was, I think, just the general frustration with Representative Hunter pushing them hard on civilian hostages and their awareness that I was speaking to Representative Hunter about all of this.”

Col. Amerine said that at one point, the FBI threatened the father of a captive not to speak to Mr. Hunter.

“I mean, just atrocious treatment of family,” he testified.

He also gave the public an inside look at internal hostage release debates.

He said his office was working on a blockbuster trade that would release Bergdahl and four others in exchange for Haji Bashar Noorzai, a notorious Afghan heroin smuggler whom the U.S. enticed to enter the U.S. in 2005 and then arrested him. Imprisoned for life, he had worked with U.S. forces fighting the Taliban.

“So we were able to reach out to the Noorzai tribe itself that we believed could free the hostages, and we made a lot of progress on it,” he testified. “I briefed it widely, but in the end, when the Taliban came to the table, the State Department basically said it must be the five for one. That’s the only viable option we have. And that’s what we went with.”

Ironically, on the same day Col. Amerine was evicted from his office, the U.S. mistakenly killed American hostage Warren Weinstein via a missile strike on an al Qaeda hideout in Pakistan.

Five Americans have been killed in captivity since 2001, four at the hands of extremists.

“We were the only DOD effort actively trying to free the civilian hostages in Pakistan, and the FBI succeeded in ending our efforts the day the dysfunction they sought to protect killed Warren Weinstein,” Col. Amerine testified.

The officer testified that the Army “will not uphold this soldier’s right to speak to Congress” under the whistleblower act.

“The outpouring of support from fellow service members has been humbling,” he said. “Worst for me is that the cadets I taught at West Point, now officers rising in the ranks, are reaching out to see if I’m OK. I feared for their safety when they went to war, and now they fear for my safety in Washington.”

Col. Amerine has filed a whistleblower retaliation complaint with the Defense Department inspector general. In the complaint, he listed the pieces of information he provided Mr. Hunter. He said the Pentagon’s Joint Staff, which works for the chairman of the Joint Chiefs Staff, concluded that there was no classified information.

Mr. Kasper, the congressman’s chief of state, said, “The Joint Staff already determined that all the information and sources within Amerine’s coordination with Rep. Hunter and Congress is unclassified. McHugh and his team have shown that they retaliate, and hide behind process, so there’s no confidence that the Army will actually do the right thing.”

Meanwhile, Mr. Hunter has asked the same inspector general to investigate whether the Army is springing accusations against personnel as pure retaliation.

Mr. Hunter wrote to Jon T. Rymer, the inspector general, about three soldiers, including Col. Amerine, against whom he believed Mr. McHugh retaliated. He asked for an inspector general’s investigation into Mr. McHugh’s use of the Criminal Investigation Command (CID).

“Specifically, my concern is that the Army — under the leadership of Secretary of the Army — has used CID for the purpose of influencing actions/outcomes and retaliating against soldiers,” he wrote.

“I have personally met with the Federal Bureau of Investigation on the developments leading up to the Army investigation,” Mr. Hunter told Mr. Rymer. “An investigation, I firmly believe, was not warranted but continues to be unjustifiably delayed.”

The Army referred The Times to CID to answer Mr. Hunter’s charge against Mr. McHugh.

Chris Grey, a spokesman for CID, said, “We reject any notion that Army CID initiates felony criminal investigations for any other purpose than to fairly and impartially investigate credible criminal allegations that have been discovered or brought forward.”

An Army spokesman has said, “As a matter of policy, we do not confirm the names of individuals who may or may not be under investigation to protect the integrity of a possible ongoing investigation, as well as the privacy rights of all involved. However, I note that both the law and Army policy would prohibit initiating an investigation based solely on a soldier’s protected communications with Congress.”

The Army told Mr. Hunter in a letter that it was investigating Col. Amerine for the unauthorized release of classified information, the charge leveled by the FBI.

“Am I right? Is the system broken?” Col. Amerine asked last week. “I believe we all failed the commander in chief by not getting critical advice to him. I believe we all failed the secretary of defense who likely never knew the extent of the interagency dysfunction that was our recovery effort.”

• Rowan Scarborough can be reached at rscarborough@washingtontimes.com.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.