OPINION:

In interpreting the law, context is everything and it is nothing. Today is the 800th anniversary of the most famous law in the English-speaking world, known as Magna Carta (Latin for ’Great Charter’). Over its life, Magna Carta has received many accolades as a foundation for our law and Constitution. William Pitt, Great Britain’s prime minister in the 1760s, said Magna Carta was ’the Bible of the English Constitution.’ John Adams before the Revolution saw Magna Carta as proof that England and its colonies had ’a government of laws, and not of men.’ Every century since is filled with praise for its strength as a bulwark against tyranny. Heady stuff for a one-page document made in 1215.

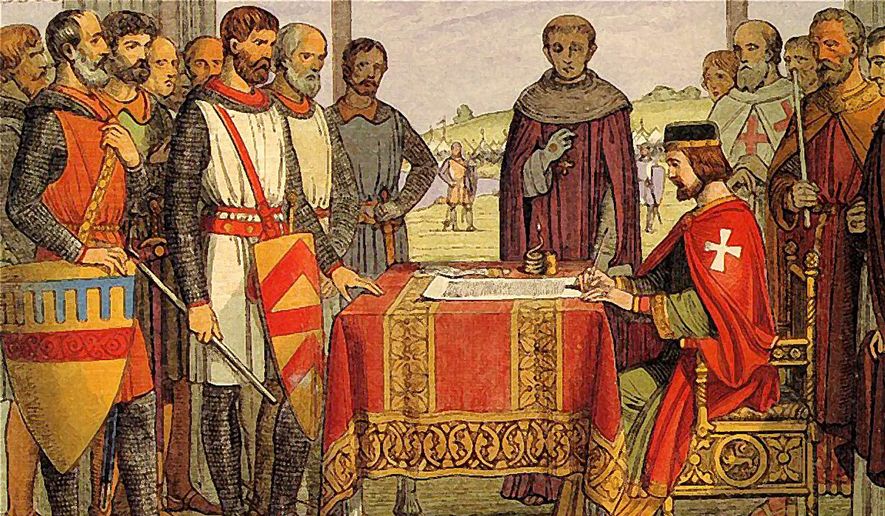

The early history of Magna Carta does not show many signs of its eventual stature. Although Americans see it as the ancestor of our Constitution, what it was at the time was in no way clear either to the king and barons assembled at Runnymede, nor to the rest of the kingdom. Few in England would have heard of it, since it was almost immediately declared null and void by the pope, and the war it had ended between the barons and King John heated up again. Soon after its publication, it was copied into lawbooks sometimes alongside forged law codes and at other times with authentic statutes. Within 10 years of 1215, so many different versions were circulating that learned contemporaries were confused about which king signed it, and what it actually said. Sorting out the confusion took another five centuries.

The field from which it grew appears an unlikely place to produce a statement of fundamental liberties. Medieval England was a strange place. The barons and king at Runnymede did not share our values. These “framers” of Magna Carta believed in elves and Camelot, burned heretics and witches, and murdered Jews with hardly a second thought. The “abstract” principles embedded in Magna Carta — like jury trial, due process, and habeas corpus — cannot be scrubbed of these beliefs. As is true for all people of the past and present, no simple motive drove the barons. Instead, they acted from a mix of lofty idealism and hardened self-interest. So although the barons believed they represented not just themselves, but also the notional “Community of the Realm” which included all the English, they imagined this “Community” with power confined to the already powerful.

Nevertheless, after 1215 Magna Carta appeared to mean something to the people who mattered, despite its annulment, repudiation by the king, hibernation during invasions by the French and civil wars, neglect by brutal and overweening Tudor sovereigns, and the fickle survival rate of documents written by hand on pages made of animal skin. Magna Carta survived all of these threats, but never as the same law from one reign to the next. One thing it was not during its first four centuries was a statement of fundamental liberties and rights held by everyone in England, rich or poor, male or female, Christian or Jew.

It was the brilliant and pugnacious parliamentarian, Edward Coke, who made it into the most famous of all charters of freedom. Coke was locked in battle with autocratic English kings, James I and Charles I, and used his position as Chief Justice from 1606 to 1616 to extend the interpretation of Magna Carta’s rights beyond what the rich nobles who framed it intended. What Coke did was quite simple. Where Magna Carta’s barons intended a narrow interpretation of liberties and rights, Coke ruled instead that these rights were meant for all men. And it was Coke’s interpretations the colonists in far-off America read. And these colonists, from New Hampshire to Georgia, had good reason to believe what Coke had written. They had proof that these rights were theirs by law. The royal charters for their colonies guaranteed them the enjoyment of all the rights of Englishmen. When colonists demanded these rights, they wanted Coke’s interpretations, not those of the Magna Carta barons.

Coke’s redirection of Magna Carta was a very good thing. Most of us would agree that respecting the original intention of any law is not necessarily the most sensible path to justice. Attempting to hold to that intention may keep laws predictable, but anyone who has worked in law knows that predictability has no necessary relationship with justice. And when notions of justice expanded in Coke’s day, so he ensured that the interpretation of laws kept pace.

The Magna Carta barons’ and Edward Coke’s achievements were milestones on the road toward protecting citizens against the state. The legacy of Magna Carta, nevertheless, is double-edged. It shows us how important justice is, but also how imperfect it is when administered. We have far to go before we can say that Magna Carta’s principles of justice are enjoyed by all of us. Now, after its first 800 years, Magna Carta still has work to do.

• Bruce O’Brien is the academic lead of the University of London’s Early English Laws project and professor of Medieval history at the University of Mary Washington.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.