OPINION:

The U.S. Supreme Court must soon decide whether to hear a handful of cases that present a persistently stubborn question: In a class-action lawsuit, just what exactly is a class?

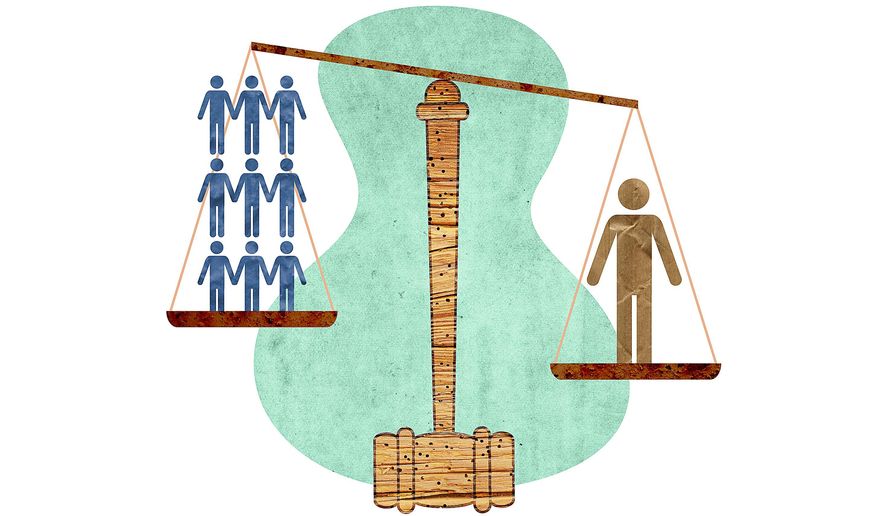

In class actions, lawyers seek damages on behalf of individual plaintiffs who represent hundreds, thousands and sometimes even millions of others making similar claims and alleging common injuries. The Supreme Court has in recent years tried to bring a measure of consistency to the central issues — who can join a class and how to measure damages — only to find the lower courts repeatedly disregarding their decisions.

Indeed, the John G. Roberts court can be forgiven for having thought it had settled the class-action question with its rulings in Wal-Mart v. Dukes (2011) and Comcast v. Behrend (2013). Taken together, these decisions established the legal requirements for plaintiffs to pursue a class-action lawsuit: The plaintiffs had to prove measurable and common harm, and they had to demonstrate that common issues predominated over individual ones. With the precedent set by these two decisions, lower courts finally had a clear standard to follow when evaluating whether to certify a class of plaintiffs.

But it hasn’t worked out that way.

While some lower courts have followed the Wal-Mart and Comcast standard, many others have disregarded it and allowed questionable class actions to proceed to trial, often with hundreds of millions of dollars in liability at stake.

A diverse group of American corporations, including Tyson Foods, Dow Chemical, Allstate Insurance and Wal-Mart, is now asking the Supreme Court to once again step in and establish some order and rationality in a class-action system run amok. It is critical that the Supreme Court do so by taking up these cases.

While the nature of the claims in the cases vary from wage and hour in Wal-Mart, Tyson and Allstate, to alleged price-fixing in Dow, the central questions presented are the same: Can a class that includes plaintiffs who suffered no actual harm be certified, and can statistical sampling be used to derive “average damages” if such a figure actually overcompensates many claimants in the class? These are questions of basic fairness and equity that the Supreme Court must resolve.

These cases are particularly ripe for Supreme Court review as they present the justices with the rare opportunity to review class certification issues post-jury verdict.

Too often, corporate defendants feel compelled to settle class-action lawsuits before a jury can decide the merits. But here, the companies involved were courageous enough to fight to the end and endure big jury verdicts — in Dow’s case a staggering $1.1 billion — all in the belief that Supreme Court precedent was squarely on their side.

These cases — with their full trial and appellate records — will allow the justices to answer crucial questions such as whether the plaintiffs proved that all class members were similarly situated and suffered actual injury and ascertainable damages. And did the defendants have an opportunity to show which claimants were not injured, and how injury varied? The facts of the cases suggest the answer to these questions is a resounding no.

Had Dow been able to offer a full defense in the case alleging coordinated price increase announcements, the company could have shown that buyers actually negotiated away proposed price increases or moved their business elsewhere, and, as a result, suffered no actual harm from the alleged collusion. But Dow was prevented from proving at trial that its buyers had vastly different experiences and were, therefore, not “similarly situated.”

In Wal-Mart’s case, an expert for the plaintiffs extrapolated underpayments to 187,000 company employees from small, unrepresentative samples. The class action format barred Wal-Mart from showing which employees were actually uninjured. An artificial calculation replaced actual facts.

Cases like these expose the stark truth that modern class actions are not about addressing true grievances shared by a common set of plaintiffs. Instead, their goal is to amass large classes to ratchet up pressure on companies and force quick and lucrative settlements.

In Wal-Mart and Comcast, the Roberts court started to fix the class-action system. With these new cases, it now has the perfect opportunity to finish the job.

• John Engler, a former Republican governor of Michigan, is president of the Business Roundtable.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.