OPINION:

In 2009, as intelligence reports confirmed that Iran — the world’s leading state-sponsor of terrorism — had resumed its nuclear weapons development program, the efforts of American policy officials to reverse it focused first on Iranian vulnerabilities. What critical commodity or service essential to daily life in Iran might be restricted by sanctions and thereby influence the government of Iran to change course? It didn’t take long to identify such a strategic commodity: gasoline.

Paradoxically, although Iran has very substantial oil reserves, years ago it adopted the practice of selling its crude to foreign refiners who would provide gasoline and other petroleum products back to Tehran. Consequently, a successful allied effort to restrict the export to Iran of gasoline and other consumables — and, of course, to prohibit financial institutions from enabling such transactions — would surely get the attention of Iranian leaders.

At that point something unusual happened in Washington. An experienced group of outside national security professionals at a local nonpartisan think tank, the Foundation for Defense of Democracies (FDD), began to focus with laser precision on identifying which measures would restrict which products, by which companies, in what countries, with the help of which banks, producing a mountain of incisive knowledge. FDD immediately offered the results of its research pro bono to the Treasury Department, the U.S. Congress, the United Nations and allied governments.

The results have been truly extraordinary. In very little time, this team under the leadership of FDD President Cliff May and Executive Director Mark Dubowitz became the go-to source of knowledge regarding Iran’s trading practices for the House and Senate and for governments throughout Europe and much of the world. Before long legal sanctions with real bite were enacted and squeezed the Iranian economy with evident political impact. As a result, for the first time in its history, Iran agreed to talks with the five permanent members of the U.N. Security Council (plus Germany), focused on measures to circumscribe its nuclear weapons program.

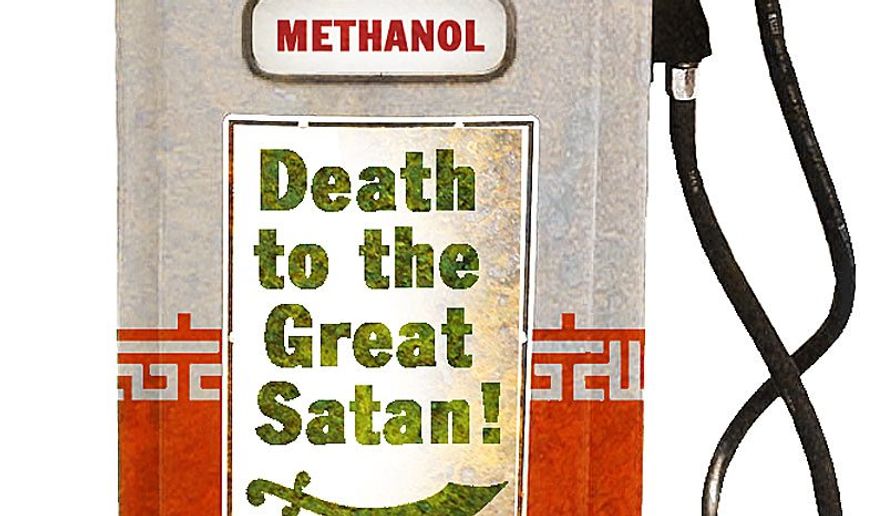

Since 2007, however, due to the effectiveness of our sanctions, and in validation of the aphorism that “necessity is the mother of invention,” Iran has been driving to build the world’s largest methanol plant.

Recognizing that methanol is a proven, clean-burning, high-octane fuel (race-car drivers love it) that can replace gasoline as a fuel in Iranian or other vehicles anywhere, Tehran is looking to methanol to provide the path to overcome the effectiveness of U.S. and allied sanctions.

U.S. automobile manufacturers confirm that it takes less than $90 per vehicle to enable a car to run on methanol; indeed a good gas station mechanic in Tehran could do it for very little more than that. Further, methanol can be easily made from natural gas and Iran has the second-largest natural gas reserves in the world.

It is worth noting that three years ago, MIT conducted an exhaustive analysis, led by professor Ernest Moniz, currently secretary of the Department of Energy, of how best to exploit the huge windfall production of shale gas that is underway in our country. Its answer: turn shale gas into methanol. Our own automobile manufacturers like methanol for many reasons — not least that as a high-octane fuel, it would enable Detroit to build high-compression engines that are lighter, more powerful, have fewer harmful emissions, and help them meet new, higher CAFE standards more easily.

But back to the geopolitics of Iran’s strategy for outflanking U.S. and allied sanctions. Consider the following: Today, 20 million automobiles are made annually in China, yet China has very little petroleum and must develop a source of fuel to run those 20 million cars. A few years ago, China sent a delegation of energy experts to the United States to survey what our studies were concluding with regard to transportation fuel. They returned to China convinced that the best alternative to gasoline was methanol. Not long after that, China pledged to Iran that it would invest $100 billion in Iran’s energy industry. What should we conclude from the foregoing?

• Thanks to FDD and a bipartisan effort in Congress and with allies, sanctions have worked and coerced Iran into engaging with us to discuss restrictions on their nuclear weapons program.

• Iran has learned a sobering lesson regarding its own vulnerabilities and has turned adversity into victory. Their new energy policy — to turn their massive gas reserves into methanol — bodes fair to enable them to tamp down internal stresses related to gasoline shortages and to strengthen their relationship with China, which will render our future efforts to add additional sanctions against them more difficult to achieve.

• Iran has promoted its interests masterfully in the negotiation and outmaneuvered the P5+1 nations at every turn. Unless the current terms are changed to allow for unimpeded access by verification teams to discover violations of the agreement — an unlikely prospect — Iran will be able to continue development of nuclear weapons, will receive an immediate infusion of cash from accounts blocked during the negotiation by sanctions, and a tide of new investment from western companies.

• Within a few years, Iran will be producing the best vehicle fuel on the planet and capturing a huge global market for it while the United States is still paralyzed by environmental uncertainties.

• Robert McFarlane served as President Reagan’s national security adviser.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.