OPINION:

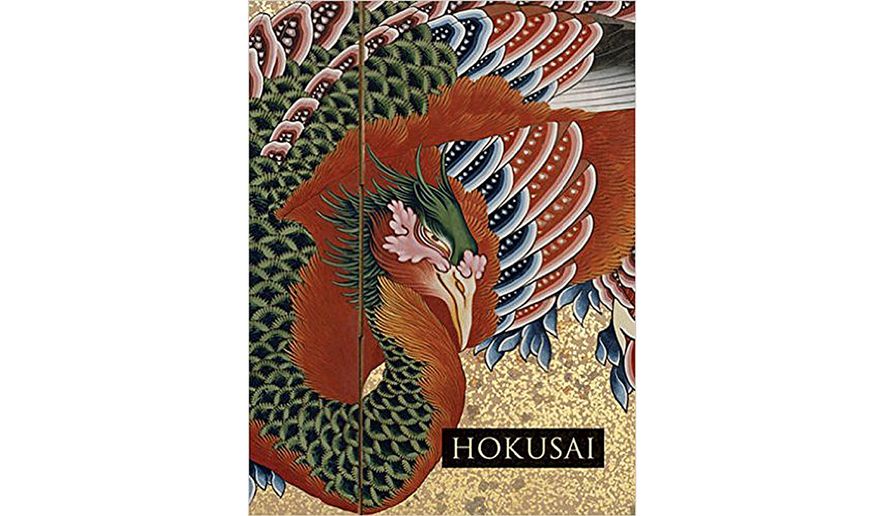

HOKUSAI

By Sarah E. Thompson

MFA Publications, $29.95, 176 pages

Between the 17th and 19th centuries, ukiyo-e was one of the most influential artistic styles in Japan. Composed of woodblock prints and traditional painting, typical scenes included historical events, folk stories, beautiful women and the rigors of daily life.

There were great artists in the ukiyo-e movement, including Hishikawa Moronobu, Utagawa Hiroshige, Kitagawa Utamaro, Okumura Masanobu and Utagawa Kuniyoshi. The most well-known and, arguably, most talented was Katsushika Hokusai.

Sarah E. Thompson delicately examines this art master’s life and career in her book, “Hokusai.” She’s the assistant curator for Japanese Prints at Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts — which houses the largest collection of Japanese works (outside of Japan) in the world. This museum also held the world’s first exhibit of the artist’s work in 1892-93, “Hokusai and his School.”

Ukiyo-e was the first type of Japanese art that western countries saw, appreciated and collected. Ms. Thompson’s book notes the “prolific and versatile” Hokusai, who was a “major source of inspiration for the Japonisme craze in Europe and America in the late nineteenth century,” remains “by far the most popular” from his country.

Hokusai was born Tokitaro Kawamura in 1760 in the Katsushika district of Edo (now Tokyo), Japan. He was adopted by his uncle, Nakajima Ise, “a mirror polisher in the service of the shogun, who wanted an heir to succeed him in his prestigious position.”

Fortunately, he followed a different career path.

The growth and development of Hokusai’s artistic talent remains a mystery. Ms. Thompson writes, it’s “somewhat surprising that he did not receive training from the Kano school of art, the official painters to the shogun and the dominant force in art education in Edo-period Japan.” The author states that, as far as we know, he had “no formal training in drawing and painting until he joined the studio of the ukiyo-e artist Katsukawa Shunsho.”

With Shunsho serving as his mentor and teacher, Hokusai began to master the woodblock prints and painting skills that symbolize his art.

Some of his early work included sumo wrestlers, attractive women, children, warriors and Chinese scenes. He also engaged in uki-e, or “floating pictures,” which was “an exaggerated form of Western vanishing-point perspective to create startlingly realistic scenes.”

Hokusai was “constantly aware of the relationship between three-dimensional objects and two dimensional pictorial surface.” He painted on “flat surfaces” as well as “rounded shapes of festival lanterns.” He was extremely fascinated by “the interplay of reality and illusion.”

As Joan Wright (Bettina Burr Conservator, Asian Conservation) and Philip Meredith (Higashiyama Kaii Conservator of Japanese Paintings) write in one book’s chapters, Hokusai was also “an acute observer of the natural world and had a lifelong fascination with optical effects.” His use of various techniques and materials “wasn’t unique,” but he was “particularly adept at incorporating elements from each discipline, always moving effortlessly between painting and print design.”

Upon his mentor’s death in 1793, Hokusai became a “very successful designer of surinomo, privately commissioned prints.” He engaged in book illustrations, lavishly designed board games, and toy prints. His middle years are described by Ms. Thompson as a “time of great creativity and exploration of artistic possibilities.”

This is where his legendary status began to develop.

The book contains many full-color illustrations of Hokusai’s art, including “Interior of a House of Pleasure” (1808-1813), “Picture Book of the Two Banks of the Sumida River at a Glance” (1804), “Rare Views of Famous Landscapes” (1834-35) and “A Tour of Waterfalls in Various Provinces” (1832). Pages from his astonishing woodblock print book, “One Hundred Views of Fuji” (1834), are also profiled.

One of Hokusai’s best known works is “Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji,” made between 1830-31. This extraordinary series of landscape prints “explicitly contrast the striking triangular shape of the mountain with triangles, rectangles, trapezoids, or curved shapes formed by other elements of the design.” Some recognizable prints include: “Tsukudajima in Edo in Musashi Province,” “In the Mountains of Totomi Province,” and “Under the Wave off Kanagawa, or The Great Wave,” described by Ms. Thompson as “not only the most famous of all ukiyo-e prints, but arguably the most famous image in all of Japanese art in the eyes of the world.”

When Hokusai died in 1849, Thompson writes, “his last words are said to have been a plea for just five or ten more years to paint.” He didn’t get his wish, but he left a lifetime of exceptional art for people to enjoy.

• Michael Taube is a contributor to The Washington Times.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.