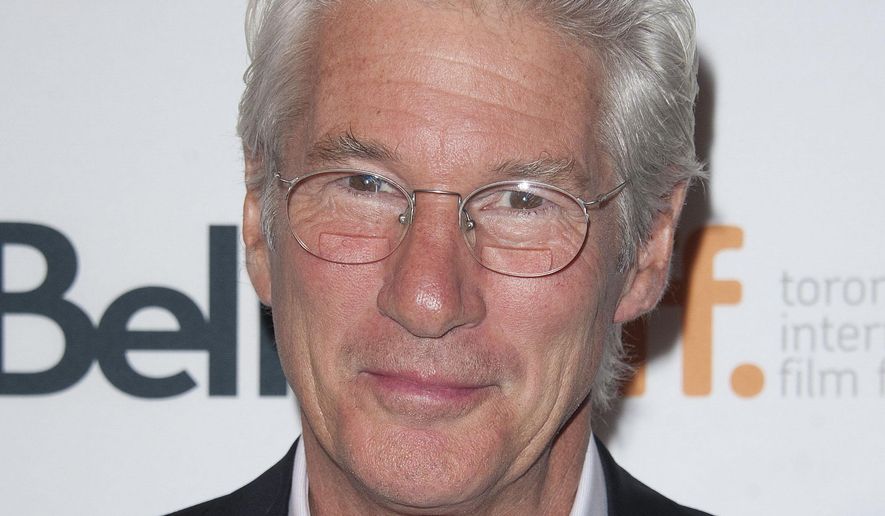

Even Richard Gere had a tough time panhandling.

For his role as George, a homeless man suffering from mental illness in the upcoming film “Time Out of Mind,” the actor went “undercover” in New York, standing on street corners and beseeching people for change.

“I made a buck and a half. I was very bad at this,” Mr. Gere said Thursday at the National Conference on Ending Homelessness in Washington, hosted by the National Alliance to End Homelessness at the Renaissance Washington DC Downtown Hotel.

Although his anecdote elicited laughter from the luncheon crowd, Mr. Gere stressed that the ongoing issue of homelessness in America is far greater than a wealthy movie star trying to get into character. The alliance estimates that, on any given day, 578,424 people in the United States experience homelessness. A good number of them are mentally ill or suffering from addictions. The burden on taxpayers for medical care and housing is extraordinary.

“It’s not about numbers. Numbers doesn’t touch anybody,” Mr. Gere said. “The more numbers there are, the [more numb] we get.”

The actor stressed that, rather than try to solve the issue of housing every homeless person, it is more important to work with people on an individual basis.

“[It’s more about how] we see one face in the present time and engage in the present time,” he said. “We’re not perfect people, but even some little bit of empathy, of connection, opens us all up.”

“Time Out of Mind,” which opens in September, follows George’s peripatetic existence, walking the streets of New York, seeking out the next bed or the next meal. Mr. Gere, who is a Buddhist, described his time in character as George as almost “monklike.”

It was “very simple, living in the moment,” he said of the role. “I’m hungry, I’ll try to find something to eat. I’m tired, I’ll try to find somewhere to sleep. There’s no job, there’s no appointments.”

Mr. Gere, who said he was never recognized while “living” as George on New York street corners, came to understand the fear people have of the homeless. In addition to turning down his entreaties for change, passers-by would even avoid eye contact.

“I was a black hole that people were terrified [they] were being sucked into,” he said. “We ended up shooting for about 45 minutes [on the street], and no one paid any attention to me.”

On its website, the National Alliance to End Homelessness says it “works collaboratively with the public, private, and nonprofit sectors to build state and local capacity, leading to stronger programs and policies that help communities achieve their goal of ending homelessness.” The nonprofit is working to one day make homelessness a thing of the past.

Mr. Gere said that even in the shelters he and director Oren Moverman visited, they found that America’s homeless still crave not only connection, but also community.

“In simple ways, [you’re] trying to find a connection,” he said. “And I think what we were able to portray in the shelter scenes is this level of trying to find some level of community even there. One [person had been in] prison, one [was in] the military. In a simple way, you’re protecting yourself because you’re terrified” of the continuing struggle just to survive, he said.

Mr. Gere picked up a great deal of his philanthropic tendencies from his father, who for decades delivered food for Meals on Wheels. His father, Homer, now 93, told his son that bringing sustenance to the less-fortunate was as much about brightening up people’s day as filling their bellies.

The elder Mr. Gere told his son, “’The reality is, Richard, I like to go and jolly people up. I like to make a human connection that’s more than the food,’” Mr. Gere told the Renaissance audience. “’I come and spend time, I joke around, I hang. This is what I do.’”

Mr. Gere related that he and his community came together to help a homeless man in his hometown in rural Pennsylvania.

“He was fed by a connection and familiarity,” he said. “Even on that level, that’s community.”

Mr. Gere made the case that his small-town upbringing instilled in him a care for his neighbors that he feels is somewhat lost in America’s big cities, where the majority of homeless people are to be found.

“We live in buildings but don’t know” our neighbors, he said.

In the same vein, he said, many working people in a shaky economy are frightened that they, too, might wind up on the street — that we all may be one disaster away from penury, especially when the prevalence of mental illness in the general population is factored in.

“You’re always just a few [moments] away from losing it,” he said.

However, the actor hopes that “Time Out of Mind” can be a useful tool for the National Alliance to End Homelessness to continue the conversation about helping America’s poor and one day putting an end to homelessness.

“If I can help a little bit and lift up in your communities, I’m happy to do it,” he said.

• Eric Althoff can be reached at twt@washingtontimes.com.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.