A leading Chinese Communist Party newspaper is savoring Facebook’s decision to block a leading exiled Chinese dissident’s account, praising the company’s voluntary move as yet another sign that Chinese human rights activists deserve punishment not only by the communist government but also by leading Western social media outlets.

On Dec. 28, Liao Yiwu, one of the most prominent Chinese dissidents now in exile in Germany, received a warning from Facebook about posting a photo of a streaking Chinese dissident in Stockholm, who protested the granting of the 2012 Nobel Literature Prize to the pro-government writer Mo Yan. Because the private parts of the protester are covered with a Photoshopped portrait of former dictator Mao Zedong, the iconic photo has been widely circulated in some mainstream media outlets in Europe, and was deemed acceptable by most Internet decency standards. But a couple of days later, Facebook informed Mr. Liao that his account had been suspended, holding out the threat of permanently deleting the account if he does not comply with Facebook’s demands.

This action is preceded by some of Facebook’s recent decisions to delete information in individual accounts most likely deemed unacceptable to Beijing, including a video clip showing a Tibetan Buddhist monk’s immolation in protest of the Chinese government.

Mr. Liao was furious and believes the incident was an act of self-censorship by Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg in an effort to placate the Chinese government. Mr. Zuckerberg is currently trying to gain market access to China, where Facebook is banned entirely. “I didn’t knuckle under the Communist Party, and I won’t knuckle under [to] Facebook,” Mr. Liao defiantly responded.

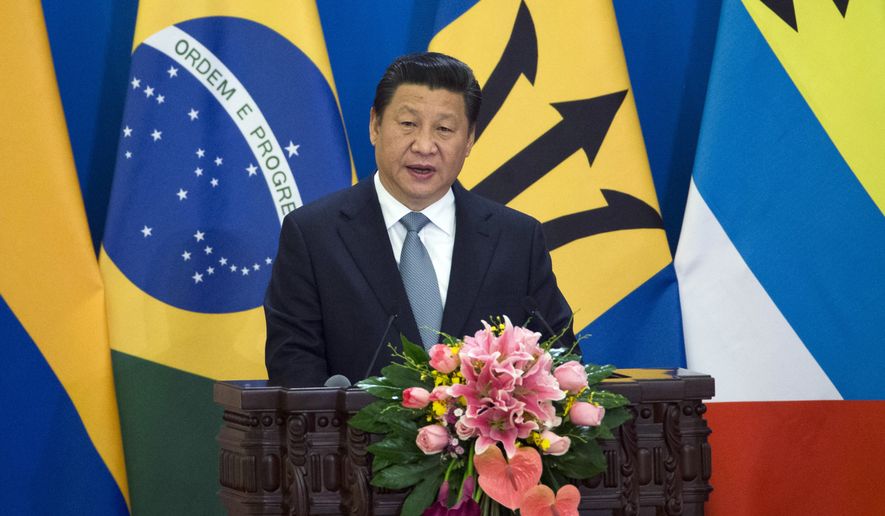

Mr. Zuckerberg has been criticized for his eagerness to curry favor with Chinese leaders, highlighted by his invitation of China’s chief Internet regulator and cybercensor to Facebook headquarters in California in early December. During the visit Mr. Zuckerberg proudly displayed to his guest a copy of the selected works of China’s Supreme Leader Xi Jinping.

The Chinese government was delighted by Facebook’s decision to block Mr. Liao’s account. The propaganda value of Facebook’s action for Beijing proved hard to miss.

“Facebook’s actions are decisive. Liao doesn’t only have conflicts with the Chinese government. Western opinion mechanisms cannot bear his behavior either,” wrote the Beijing-based newspaper Global Times in an editorial published Jan. 5. The newspaper is a subsidiary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party’s mouthpiece, People’s Daily, renowned for its unabashedly anti-Western diatribes and die-hard support of the party line.

But Global Times went further, turning Facebook’s move into a general indictment against Western criticism of China’s comprehensive censorship and a universal endorsement of the regime’s suppression of the free flow of information. “Blocking [Facebook] accounts shows freedom of speech has limits,” the headline in the Global Times editorial stated.

Facebook officials adamantly denied that the blocking of Mr. Liao’s account had anything to do with politics. But the Global Times disagreed. “It surprised many that Facebook suspended Liao’s account,” the editorial noted. “After all, the photos posted by Liao are not simply about nudity, but politics.”

Facebook’s blocking of Mr. Liao’s account has also provided fodder for the government to demonize Chinese political dissidents as troublemakers, not just in China but around the globe, asserting they are deserving of harsh punishment by all governments and societies.

“Although China differs with Western countries in its system and is still learning how to properly deal with the behavior of dissidents, from another perspective it shows that these dissidents do not play a constructive role in real life, no matter if they are in China or abroad. They are more likely to have conflicts with society,” Global Times stated.

China is among the world’s most repressive nations when it comes to freedom of speech. Year after year, China is ranked near the bottom of the press freedom index by all major monitoring organizations. In 2014, for example, Reporters Without Borders ranked China 175th out of a total 180 countries surveyed, slightly above rogue nations such as Syria and North Korea in restricting press freedom. China has the world’s largest number of Internet users but, according to Reporters Without Borders, is also “the world’s biggest prison for netizens,” with more people in jail for expressing opinions online than the rest of the world combined.

The Global Times regards Facebook’s action against Mr. Liao as a setback for exiled Chinese dissidents and a triumphant blow to Chinese dissidents inside the country, while calling for continuing crackdown on dissidents in order to force them to abandon their cause.

“Authorities should stick to the red line in the law. Dissidents may feel constrained and give up their illusions,” said the editorial. “The setbacks they suffer overseas may offer some lessons for those within the country.”

• Miles Yu’s column appears Fridays. He can be reached at mmilesyu@gmail.com and @Yu_miles.

• Miles Yu can be reached at yu123@washingtontimes.com.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.