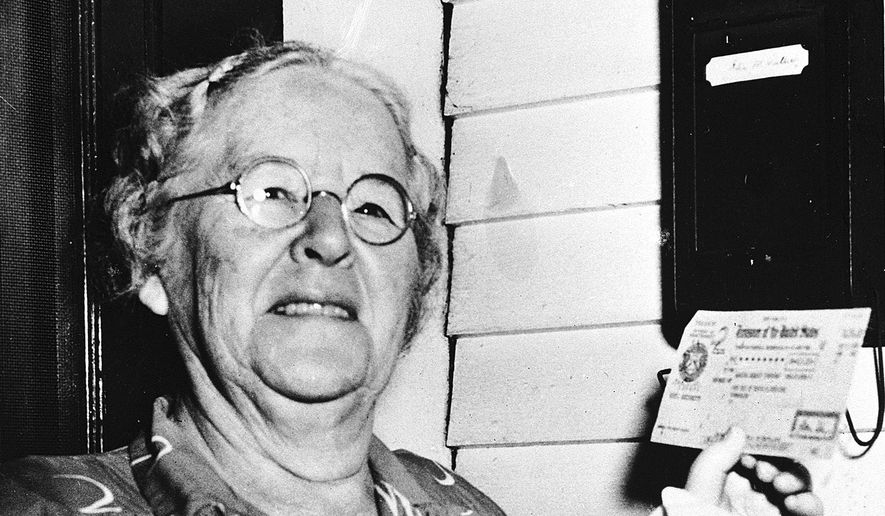

LUDLOW, Vt. (AP) — Seventy-five years ago, the government cut 65-year-old Ida May Fuller a check. It was numbered 00-000-001 — the first Social Security payout.

Fuller, of Ludlow, Vermont, didn’t realize it at the time, but her check helped launch the granddaddy of all entitlement programs. And it secured Fuller, who never married and had no children, a place in American history.

Today, even as its future lies in financial uncertainty, many consider Social Security one of government’s biggest successes. But in its infancy it was hardly a sure thing, and not well understood by many, including Fuller.

“It wasn’t that I expected anything, mind you, but I knew I’d been paying for something called Social Security and I wanted to ask the people in Rutland about it,” she’s quoted as saying in a Social Security Administration document.

Fuller, known around Ludlow as “Aunt Ida,” died in 1975 at age 100. By then, she had already become a celebrity of sorts, with a few previous brushes with fame.

Fuller was born on a farm 2 miles outside Ludlow, then a mill town and now a ski town, in the heart of the Green Mountains. Future President Calvin Coolidge was three years ahead of her at the Black River Academy, now a museum.

Later, she worked as a secretary for the Vermont law firm of a Ludlow lawyer who had been Coolidge’s attorney general.

In early November 1939, she passed by the government office in the larger city of Rutland and decided to pop in to ask about Social Security. While there she was urged to apply for benefits, not realizing she’d get the first check. That Jan. 31, 1940, check was for $22.54, a little less than the $25.75 that the agency had been deducting from her paycheck in the previous three years.

By the time she died in 1975 at age 100, she had received a total of $22,888.92 in benefits. Near the end of her life, when she was living with a niece, she told a reporter that the payments “come pretty near paying for my expenses.”

And that was the idea.

“It is hard for us to imagine what life was like for seniors and the disabled before Social Security,” said Vermont’s independent Sen. Bernie Sanders, a vocal supporter of the system.

On the 10th anniversary in 1950, there was 6-minute movie made by the Social Security Administration. A 1955 article called Fuller “a kindly, likable, practical and placid woman whose ability to derive deep satisfaction from simple, wholesome living has eased her through life.”

In 1960, she received greetings from across the country. She became the subject of more media attention on her 100th birthday shortly before her death.

These days, Vermont has a reputation for liberalism, with some likening its generous social safety net to socialism. But back then, it had a reputation as a staunch anti-New Deal state in addition to being the home of Coolidge, a Republican and proponent of small government.

In 1936, voters in Vermont and Maine were the ones who didn’t support President Franklin Roosevelt for a second term. But a progressive wing of the Vermont Republican Party was beginning to emerge.

Fuller, a staunch Republican, did not support Roosevelt. In 1970, she told The Associated Press that she didn’t think there should be any more increases in Social Security payments.

“It’s been raised as far as it ought to go,” she said. “Every time they raise it, they raise the amount taken away from the working people who pay into it, and it’s just getting to be too much of a burden.”

The Social Security Administration, first led by former New Hampshire Gov. John Winant, insists it was just coincidence that the first check went to a Vermont resident.

Social Security has undergone significant changes since Fuller received her first check, including the addition of disability benefits in 1956. Today, 59 million retired workers, spouses, disabled workers and survivors get monthly payments averaging $1,194.

The latest overhaul came in 1983, when Social Security was on the brink of insolvency. Congress increased payroll taxes, cut benefits and gradually extended the age when retirees can claim full benefits. The changes shored up Social Security’s finances so it could absorb the initial wave of retiring baby boomers.

Today, Social Security’s trust funds hold more than $2.7 trillion in special Treasury bonds. But unless Congress acts, Social Security’s disability fund will run dry in 2016 and the retirement fund will be depleted in 2034, according to projections by the trustees who oversee the programs.

___

Associated Press writer Stephen Ohlemacher in Washington contributed to this report.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.