ANALYSIS/OPINION:

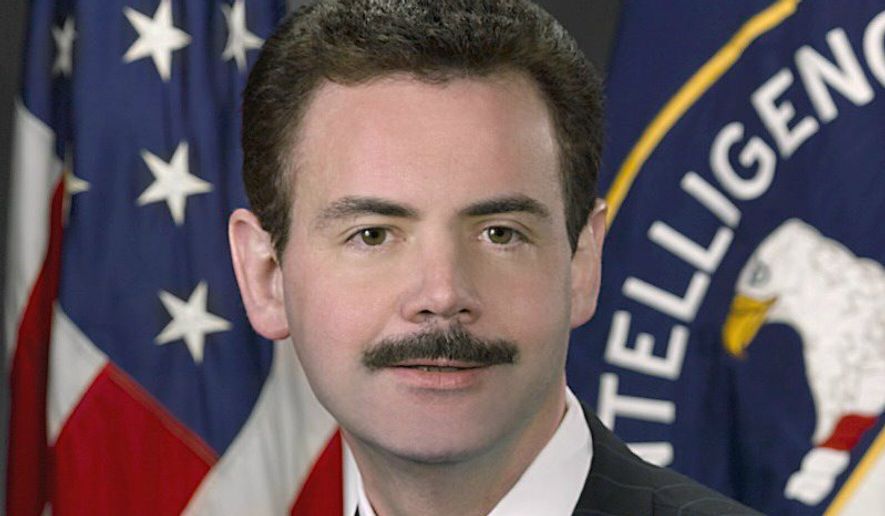

Mark Mansfield died last week. I doubt that many readers of the news, even intelligence devotees, knew about Mark. Writers of the news, however, — especially intelligence beat reporters — knew him well. He was, in a phrase he once dubbed the ultimate oxymoron, “the CIA spokesman” and — in one way or another — served the public affairs needs of nine CIA directors.

I was one of them. I shamelessly pirated him from the Director of National Intelligence’s staff to be my chief of public affairs in 2006. He wanted the job and convinced us that any lingering health issues were manageable. What a great choice. He knew the business of the agency and the business of the press and respected both. Not surprisingly, his passing is being mourned as much by the Fourth Estate as it is by the National Clandestine Service.

And therein lies a lesson. There are unarguable structural tensions between an enterprise, espionage, that relies on secrecy for its success and another, journalism, that succeeds only by ferreting out the unknown. Despite that, Mark never saw this as a battle between the forces of light and the forces of darkness.

When he cued me up to talk to an editor to try to scotch, modify or delay a story we viewed as harmful, he prompted me to begin with, “Look, I understand that we both have a job to do in defending American liberty, but I fear that the way you are about to do yours is going to make it harder for me to do mine.” Adult conversation usually followed.

A second great lesson from Mark: play it straight. Say what you can, decline comment when you must, and tell people when they’ve got it wrong, even if you can’t always get into the details. Mark understood that it was only when we tried to be open and public about the things we could talk about that we were able to really protect the secrets that we could not talk about. He crafted unclassified messages from me to the workforce that he then used to create context on issues for the press.

SEE ALSO: Mark Mansfield, childhood actor turned CIA spokesman, dies at 56

“Here’s what the Director is telling his people on that.”

And Mark was a happy warrior. That was part of his charm. Every morning he’d compare the morning intel with the morning press in my Chief of Staff’s Office and then poke his head into my office with a friendly wave and a smile as he was leaving.

But, happy or not, he was indeed a warrior. He was fierce in defending the agency when he felt it was being unfairly attacked.

The recently declassified summary of the Feinstein report recounts a September 2006 incident where a reporter contacted Mark about FBI sources challenging CIA’s account of the interrogation of Abu Zubaida. This had been a running gunbattle for years and was essentially about what finally made Zubaida talk, FBI rapport building or tough CIA questioning. Mark launched an email to agency seniors with the title “We Can’t Let This Go Unanswered,” characterized the FBI storyline as bull**** (quite accurately, in our view) and declared that “we need to push back.” Some senators saw this as manipulative or deceitful. I didn’t. I saw it as essential truth telling.

The intelligence community could have really used a stronger dose of Mark’s approach in recent years. In the cascade of revelations from Edward Snowden, the IC response has frequently been slow and flat-footed. Accusations stood for days before they were countered, and even then few responses seemed to have the fire of Mark’s “Bull****!” Curiously, there were more Bush than Obama administration officials on TV defending the current administration’s programs.

Similarly, CIA manfully pushed back on the Feinstein report’s accusations about interrogations, but it was left to a group of six former directors (including me) and deputy directors to take the gloves off in a Wall Street Journal op-ed that described “a missed opportunity,” “a one sided study,” “errors of fact,” and a “partisan attack” — all in the first paragraph. To be sure, much of CIA’s and NSA’s reticence had to do with constraints imposed on them by their political masters, but the effect was the same — late and pulled punches and a public debate that more resembled a Rorschach test than a reasoned inquiry.

SEE ALSO: Hillary Clinton undercut on Libya war by Pentagon and Congress, secret tapes reveal

Even more important, though, might be Mark’s lessons on transparency and going to the limits of saying what you can. The legitimacy of the American intelligence enterprise is dependent upon the sanction of the American people, and that sanction is increasingly conditioned on their understanding what is being done in their name. The wisest among them are not demanding the kind of detailed transparency that would be destructive of espionage efforts, but they are looking for a kind of translucence. They need to know the broad shapes and rough movements of what is going on.

Americans may have been more accepting of the 215 program — the collection of their telephone metadata — had they been told it’s broad outline by intelligence officials rather than isolated facts by a renegade contractor on the lam in Hong Kong. Similarly, when Mark supported my casually mentioning in open congressional session in February 2008 that CIA had waterboarded three people (and naming them), we both knew we were undercutting the claims of the most radical critics and (perhaps) easing the fears of calmer citizens. In any event, the facts were out there.

He was right on so many things. He was also my friend. Beyond my view, at the height of the controversy over the destruction of videotapes of some interrogations, he quietly reminded reporters that the tapes were neither created nor destroyed on the current director’s (my) watch. He said that I was just sweeping up. He also imposed on our friendship to help put a human face on the agency, booking me on NPR’s comedy quiz show “Wait, Wait, Don’t Tell Me” and cajoling me into Scripps Howard’s celebrity Super Bowl contest.

I will miss him. He was a mentor and model to so many. George Little, former Defense Secretary Leon Panetta’s senior spokesman, worked for Mark. So did Marie Harf, current spokeswoman at the State Department.

Mark, you left a big space. We’ll do our best to fill it. Goodbye, my friend.

• Gen. Michael Hayden is a former director of the CIA and the National Security Agency. He can be reached at mhayden@washingtontimes.com.

• Mike Hayden can be reached at mhayden@example.com.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.