![]() The first time children called her “The Chess Lady” in a Seattle school 10 years ago, Wendi Fischer was caught off guard. As she walked in, they started buzzing, and when she asked the teacher what they were saying, it turned out she was a minor celebrity. The children were soon asking for autographs.

The first time children called her “The Chess Lady” in a Seattle school 10 years ago, Wendi Fischer was caught off guard. As she walked in, they started buzzing, and when she asked the teacher what they were saying, it turned out she was a minor celebrity. The children were soon asking for autographs.

Ms. Fischer gained her notoriety as the public face and executive director of First Move, a Seattle-based nonprofit that teaches chess in schools using video lessons recorded by Fischer and then taught in the classroom by local teachers.

In each school she has visited since, the students already knew her: They watched and learned chess from her for an hour a week.

It wasn’t long before she embraced The Chess Lady moniker: “It’s now officially part of my title,” said the former teacher who in the past 10 years has visited nearly 200 schools around the country.

Ms. Fischer is part of a growing movement using very diverse approaches to bring the world’s grandest game within reach of even its youngest students. The theory driving the movement is that chess is much more than a game. Chess stimulates creative thinking and improves language and math performance, advocates argue, often bringing out potential in children who may not as readily click with a paper and pencil.

There is now substantial research to back up many of these claims, and there is high demand for programs that put chess in reach of grade school students. In short, while it may not be that elusive silver bullet, chess is increasingly seen as a highly valuable curriculum and mental development tool.

Across the curriculum

Recent years have produced a slew of studies from around the world showing the impact of chess on young minds. Experiments in Iran, Spain and Italy have shown strong results in cognitive, spatial reasoning, problem solving, math and reading skills.

The 2013 Italian study, for example, showed particularly strong results among non-native speakers and among children in the impoverished southern half of the country, suggesting that chess might offer stronger benefits where they are most needed.

And a 2011 study in Texas suggested that chess might be especially effective for children with special needs.

Given the strong evidence for academic impact, it is not surprising that educators have begun thinking of ways to integrate the game directly into the curriculum.

One educator who has taken this head on is Alexey Root, a former U.S. women’s chess champion who teaches a chess education class at the University of Texas at Dallas.

In addition to her online education courses, Ms. Root’s six books offer curriculum planning ideas for integrating chess into language and writing; math and science; visual arts; and the study of history, culture and geography.

One beauty of chess, Ms. Root argues, is that no one really loses because every game is a unique opportunity to learn something new.

“How did you do today?” Ms. Root asked a young chess competitor in an elevator. “I learned,” the child replied, using the chess euphemism for having lost. But, as Root points out, chess is one game where that euphemism is actually true.

Fun first

There is surprisingly strong demand for programs that offer chess instruction both in school and after school, even in the early grades.

“For every high school student I have, now I have 20 elementary school kids,” says David Brooks, director of the Knight School in Birmingham, Alabama.

Chess is the third priority at the Knight School, a for-profit after-school chess school based in Birmingham, operating chess teams for 110 locations in the city.

Chess is what they do, of course. But in order of priority, sportsmanship comes first, Mr. Brooks said, and fun second.

“I only hire non-chess players,” Mr. Brooks said. “I look for teachers who are great with kids, like the extraordinary camp counselor. All my coaches start at point zero.”

Mr. Brooks teaches all his classes using videos he records, one tactic at a time, which are then shown and supervised in each school group by 22 coaches he hires.

Mr. Brooks makes a point to never turn a child away because he or she can’t afford tuition. They offer a sliding scale tuition, which otherwise runs $90 a month, to any family that can’t afford fees, using an honor system: “If they ask for a scholarship, they get one,” Brooks said.

And while Mr. Brooks prioritizes a fun atmosphere and does not aim to create champions, he also produces some very competitive clubs. Schools within his system routinely win state championships in their age brackets.

So what does Mr. Brooks see as mission accomplished with his students? Does he want his students to be spry old men playing chess in the city park?

“Yes, I want that,” he said. “But before that I want them to be the most creative person at the table in the corporation. I want them to be the person who, when others say there is no solution here, they say, ’Oh, there are lots of solutions.’ ”

Up until five years ago, Mr. Brooks managed his chess program on the side while keeping his full-time job as a teacher at a local Catholic school. After going full time in Birmingham, he has recently hired teachers at additional locations in Alabama and Texas.

An education program

Mr. Brooks sees his Knight School as complementary, rather than competitive, with curriculum-based programs like First Move, and Ms. Fischer’s description of the latter seems to support that notion.

“First Move is an education program that uses chess as a tool,” Ms. Fischer said. Everything First Move teaches is embedded in curriculum — often math, but also reaching to statistics, the scientific method, hypothesis testing and history and culture lessons.

“When we first started,” Ms. Fischer said, “we were told we would never get an hour of class time, we would never get teachers to teach it and we will never get schools to pay for it. They were wrong on every point.”

Teachers are not intimidated because the material is presented step by step on video. After a few minutes of instruction, The Chess Lady will assign an exercise. The teacher pauses the video, and the class works on the assignment. Then they return to the recording.

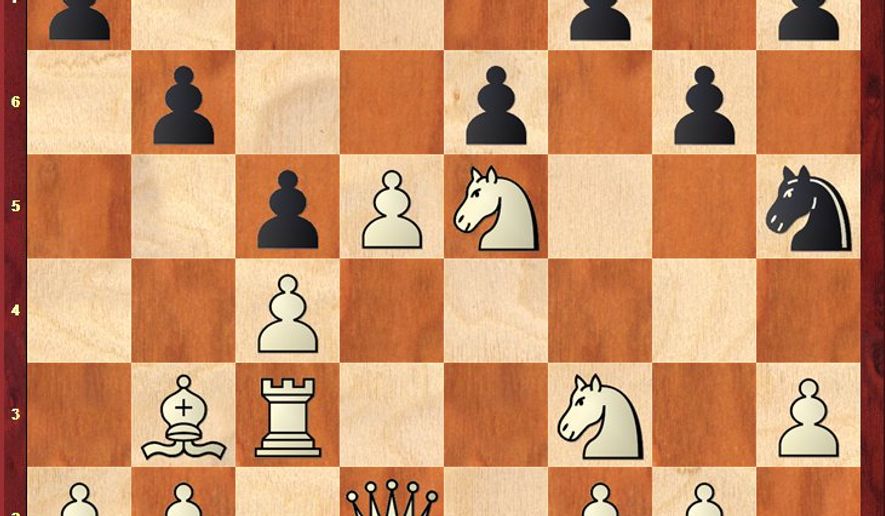

“We have a worksheet that asks, ‘Who equals the queen?’ Ms. Fischer said. The second- and third-grade students then use the point system assigned to each piece to figure all the 16 combinations that could equal the value of the queen. A rook (5), a pawn (1) and a knight (3) for example, equal the nine points of a queen. In the process, the students use pre-algebra, using the letter r for rooks and the letter p for pawns.

First Move curriculum also takes students into history, focused especially on the Middle Ages and Western Europe, but also pointing to the game’s origins in India, noting how the game spread through merchants.

“For a lot of kids, this is a different way of thinking,” Ms. Fischer said. “They may struggle in your standard math class. But when they do it with chess, it’s different.”

Students are encouraged to help each other discover the game, and schools will often hold family chess nights, which Ms. Fischer says are well-attended.

“We have a lot of schools with English language learners,” Fischer said. “A lot of their parents know how to play chess, and they know you don’t have to talk to play chess.”

She also finds social benefits. One mom said that her autistic son, who never had had any friends, had become really good at chess, and now other children in the class were engaging him, using chess as a prop.

“If that is the only benefit he got from it, that would be enough,” Ms. Fischer said. “But I know he got more.”

Please read our comment policy before commenting.